As tensions between Jews and Muslims come to a head in Jerusalem, it is worth remembering that one of Israel’s most prominent rabbis strictly forbade Jews from visiting Judaism’s holiest site in the wake of the Six-Day War.

By Nissim Leon

Recent news reflects a surge in conflict between Muslims and Jews in Israel surrounding the question of control of the site known to Jews as the Temple Mount and to Muslims as Haram Al-Sharif (the “Noble Sanctuary”). Against this background, some of the country’s leading Mizrahi-Sephardic rabbis are voicing a strident position forbidding Jews from visiting the site. Thus, alongside the Jewish-Muslim conflict in this regard, there is also an internal debate going on within religious Jewish society in Israel. On one side are mainly ultra-Orthodox (Haredi) rabbis calling, in the name of Jewish law, for Jews to be prevented from visiting the Temple Mount. On the other side are mainly Religious-Zionist rabbis and activists demanding, in the name of Jewish sovereignty, recognition of their civic and religious right to visit and pray on the Temple Mount.

The position of religiously-observant and traditional Sephardic Jews is based on a clear and unequivocal ruling by Rabbi Ovadia Yosef (1920-2013), the former Sephardic Chief Rabbi of Israel and one of the most prominent 20th century scholars of Jewish law, as well as the spiritual leader of the Mizrahi religious political party Shas. Behind recent headlines lies an ongoing ideological conflict between him and the more outspoken nationalist approaches among some (primarily Ashkenazi) Religious-Zionist circles in Israel.

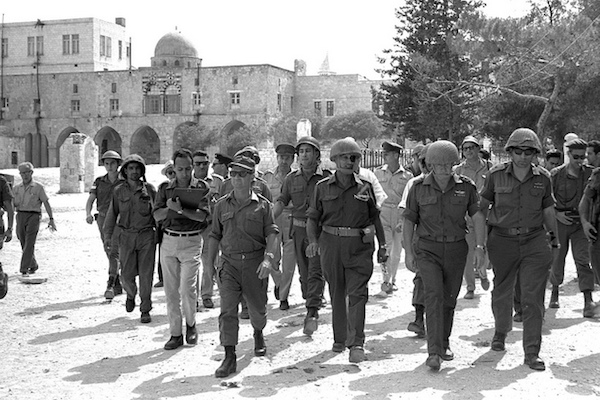

During the Six-Day War in 1967, Israel seized control of East Jerusalem, including the Temple Mount. Thus the site returned to Jewish hands for the first time since the destruction of the Temple in the year 70 C.E. The latter event marked the beginning of a long exile of Jews which, in the eyes of many secular and religious Jews alike, ended with the establishment of the State of Israel.

Many Israelis perceived the conquest of the Temple Mount as the climax of the Six-Day War and one of the defining moments of modern Jewish sovereignty. Some even interpreted this outcome as an overt sign of divine intervention, which was preceded by a period of tremendous anxiety and dark predictions in Israel. Similar nationalist and religious sentiments pervaded the central stream of the ultra-Orthodox public in Israel, affiliated with the veteran Agudat Israel party.

The results of the war raised some concerns amongst the Israeli leadership. Prime Minister Levi Eshkol, Defense Minister Moshe Dayan, and others viewed Israeli control of the Temple Mount as a possible recipe for political and religious entanglement. The main concern was that Jewish control of the site would turn the Arab-Israeli conflict from a national clash into a religious one. No more would the State of Israel be the enemy of Arab states; now, the Jewish State would be the enemy of the Muslim world. Surprisingly enough, the political leadership’s reluctance was joined by a conservative coalition of Haredi and Religious-Zionist rabbis who issued an explicit blanket prohibition against Jews ascending the Temple Mount. Their reasoning was not political but rather halakhic (pertaining to Jewish law). Their official stance had been debated in meetings of the Chief Rabbinate, and summaries of these discussions were published by the religious and general press. Against the background of a clear legal decision, there emerged the famous dissenting view of Rabbi Ovadia Yosef, who was serving at the time as a judge on the Supreme Religious Court in Jerusalem.

In a lengthy legal treatise that appeared four months after the war, and occupied half an issue of the Haredi-Mizrahi Kol Sinai newspaper, Rabbi Ovadia Yosef set forth the prohibition on Jews entering the Temple Mount precinct. Inter alia, he wrote:

It is forbidden to enter the Temple area at this time… because we are all [considered] ritually impure as a result of contact with the dead [for which there is no possibility of purification in our time]… since the holiness of the Temple [site] derives from the Divine Presence, which never leaves there… Therefore one who enters the Temple area at this time is guilty of a transgression whose sin is [spiritual] excision, and this should be publicized in order to remove a [possible] stumbling-block from the path of our people.

At the center of Ovadia’s justification for prohibiting the entry of Jews to the Temple Mount stands the principle of the place’s inherent sanctity. But among some extremist Religious-Zionist circles this very sanctity is the source of the desire to draw close to the Temple Mount. In Ovadia’s view, the sanctity of the Temple continues even after its destruction, and since Jews today cannot follow the biblically-prescribed purification rituals required in order to approach the Temple, they are all considered ritually impure. Since the boundaries of the site of the ancient temple are not sufficiently clear, anyone who goes to any part of the modern-day Temple Mount is punishable by death at the hands of heaven, for having transgressed the laws of ritual purity and impurity governing the site of the Temple.

Rabbi Ovadia Yosef’s strident warning and prohibition against Jews visiting are anchored not only in his detailed halakhic justifications, but also in the style of his article and presentation of the halakhic ruling itself.

Haredi society attaches great importance to the written word, and the manner of its presentation is no less important. In other words, the editing or literary form of the halakhic opinion or ruling can serve as a body of interpretation even for seemingly cold and objective legal arguments.

A review of Rabbi Ovadia Yosef’s ruling concerning Jews visiting the Temple Mount cannot but take note of the thin, dry and condensed language crammed with references to religious legal works. This legalistic presentation aided Rabbi Ovadia Yosef in his attempt to temper the great swell of religious sentiment and enthusiasm that came in the wake of the military victory. In the spirit of the period in which it was written, one might have expected him to include a brief narrative introduction bridging his ruling and the pathos of the nationalistic, religious sentiment that the Temple Mount conquest aroused among Jews, both religious and secular. It was an event widely perceived as nothing short of miraculous – and yet Rabbi Ovadia provided no such introduction to his article. The effect of his ruling was to transform the question of visiting the Temple Mount from a matter of national import, relating to what even then was perceived as a formative religious event, to a somewhat dry legal discussion treated just like any ordinary question of religious practice.

The ruling concerning the Temple Mount, which Rabbi Ovadia Yosef never retracted, understood the historic event from a broader perspective of the new reality and its halakhic significance. However, the wording, the presentation, the language – all of these played up to the reactionary ultra-Orthodox position of leading Rashei Yeshiva (heads of religious academies) in Haredi society at the time, who sought to lower the level of nationalistic enthusiasm that was manifesting itself in their communities. In their view, while the events of the war might indeed be important and can even be viewed as miraculous, the conquering of the Temple Mount was not the long-awaited Final Redemption. This was yet another war in Israel, with results that were certainly evidence of divine aid, but which had not changed the essentially “transient” situation of the Jews who were still considered “in exile” – even in the Holy Land, among other Jews.

The question of the Temple Mount, and later Rabbi Ovadia Yosef’s ruling permitting the relinquishing of territory for peace, are both decisions of far-reaching public significance. In both instances Rabbi Ovadia Yosef gave a detailed ruling, citing considerations and justifications – not merely a concise ruling relying on obedience to the halakhic authority. On one hand, by issuing his ruling, he (along with his followers) adopted an independent halakhic and national position that was not isolationist, as opposed to the one adopted by the Haredi stream. On the other hand, it was specifically through involvement in political questions that he engaged directly in sharp polemic with more overtly nationalist and extremist religious trends within Religious-Zionist society at the time.

The vehement position adopted by Rabbi Ovadia Yosef with regard to the Temple Mount exposed the ideological conflict, which would deepen over time, between Sephardic religious Jewry and extremist groups within Religious-Zionist society. He expressed misgivings regarding the ideological and political aspirations of these groups to lead the Zionist enterprise. Rabbi Ovadia Yosef’s approach, like that of classic ultra-Orthodox Judaism, seems to prefer the secular Zionist control of the political framework of the Jewish State to control by Religious-Zionists – not only because of the political competition that they represent, but also as a matter of principle. While secular Zionism is widely perceived in the Haredi worldview as the result of a lack of proper Jewish education, and secular Jews might still be shown the way back to tradition, Religious-Zionism is perceived as a sort of half-breed, a distortion that cannot be repaired. Indeed, Rabbi Ovadia Yosef and his followers expressed misgivings concerning Religious-Zionist ideology – although not rabbinic figures within it – on many occasions and in many sermons.

The rulings of Rabbi Ovadia Yosef, and the ideological position underlying them, have become a central halakhic approach among leaders of mainstream Sephardic Haredi Jews in Israel. His followers who continue his legacy are generally understood to maintain a similar position – specifically his family members, such as Sephardic Chief Rabbi Yitzhak Yosef, member of the Shas Council of Torah Sages, Rabbi David Yosef, as well as prominent Sephardic halakhic authorities such as former Chief Rabbis Amar and Bakshi-Doron. This same stance is taken by the Sephardic Haredi rabbis as another way of distancing themselves as much as possible from Religious-Zionist society. As noted, this aim is not altogether separate from their ideological stance. However, we must also take into consideration the bitter political struggle over the past two years in Israel between the Haredi political parties, which – to their great chagrin – find themselves in the opposition, and the representatives of the Religious-Zionist Jewish Home party, who hold key positions in the current Israeli government. The ultra-Orthodox parties view the Religious-Zionist representatives as having conspired with Yair Lapid’s secular Yesh Atid party, which demanded a government devoid of Haredi parties. Thus, the internal Jewish schism is defined not only by ideological gaps, but also by difficult contemporary political struggles.

Nissim Leon teaches sociology and anthropology at Bar-Ilan University. This article was first published in Hebrew on Haokets.

Related:

Why the status quo on the Temple Mount isn’t sustainable

The fraud that is the Temple Mount movement

How Likud became the Almighty’s contractor at the Temple Mount