In the Jerusalem neighborhood of Pisgat Ze’ev, we didn’t think of ourselves as settlers, despite the fact that we lived beyond the Green Line and our neighbors were Palestinian.

By Ofer Matan

The first Arab who stepped into our home was Sabah. The first time we met, Sabah washed his hands in our kitchen sink on a cold morning after the Jewish holidays, just before he helped my mother start her yellow Renault 12. The car already had problems with the gears by the early 80s, and Sabah would push it from behind toward the decline while she put it in neutral. She would then hit the clutch and put it into second gear, causing the motor to sputter and finally ignite. My mother knew to thank Sabah in advance, since from the moment the engine started and she could drive the car, he would fade into irrelevance.

On days he wasn’t pushing, Sabah would start his mornings with a prayer atop the cliff at the end of our street, which years later would be built up with terraced apartment buildings. It was always cold there, but his dusty jacket kept him warm. At nights he would sleep in the building site, most likely inside the concrete mixer truck. When someone on our street would lose electricity, or whenever a neighbor would feel the need to complain that her floor polish was too smooth, they would call out “Sabah, Sabah,” and he would appear.

Once, when he passed by the kindergarten, we all stood up on the fence and sang a demeaning children’s song against Arabs. I was impressed that those who ran our neighborhood could find an Arab who understood how to start engines, knew about polish, and didn’t mind our songs.

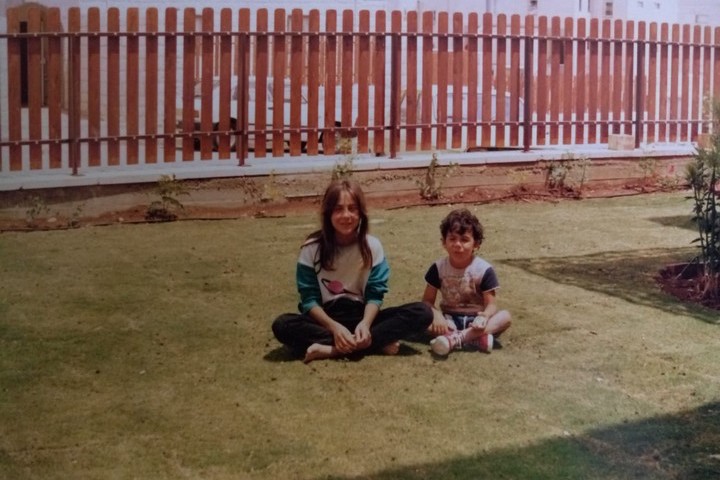

On the day the neighborhood’s last building site turned into a full-fledged building, they exchanged signatures with Sabah and wished him success. According to my calculations, this was just before Italy hosted the World Cup in 1990. I was not yet 10 years old.

Abu Ali, the second Arab who came into our home, owned a straw furniture store on the main street of Jerusalem’s Shuafat neighborhood, which we sometimes mistakenly referred to as Beit Hanina. Next to his store was a candy shop owned by Christians called Sani 2000, which sold chocolate Santas and Pepsi. My father explained that Pepsi was like a lesser Coca Cola, and that only Arabs sell it because Pepsi boycotts us. I didn’t understand a word.

One day, around the time Seoul was hosting the Olympics, Abu Ali entered our living room with a straw bookcase, which he placed in several places around the house according to my mother’s instructions. He called her “Miss” and she said he was a real artist. Years later, in 2004, when I moved into my own apartment in central Jerusalem and puzzled over what to put in one of the hallway niches, she suggested I bring a chest of drawers from Abu Ali. As if 20 years had not gone by and the man is still sitting on our narrow street, building cabinets out of wood.

The third Arab arrived with basic cable in the summer of ‘94. The World Cup was taking place in the United States, the Bulls were facing off against the Suns in the living room, and I had a bar mitzvah in the yard, catered by the La Rachelle restaurant. A mustached Arab man who wore his pants high like NBA legend Moses Malone came in equipped with a fleet of trays made of aluminum foil.

The fourth Arab was accompanied by the fifth, sixth, and seventh — his subordinates — to lay new tiles. They were lined diagonally, because my mother decided that it makes the house feel bigger. The eighth Arab came with me in October 2000, a faceless man who lives in my head until this very day.

But we are not a settlement

The first person to question everything appeared in our home in the 1970s. His name was Nissim and he smoked hash over my brother’s crib at a Purim party. I wasn’t yet in the plan, but once I was around it didn’t take long for me to hear about him. My parents were from Haifa’s wealthier Carmel area, he was from the Lower City. They were serious, he was an artist. They were together for years, he had children in all kinds of different countries.

Nissim refused to come to Pisgat Ze’ev because it was beyond the Green Line. They tried their best to show that it didn’t hurt them. It happened in the car, like most conversations, since distractions were often the best cure for my car sickness. Once in a while I would raise my head just to make sure — did we pass the Arab garages? Have we reached Zeituni? One time I even caught a glimpse of a field full of green sheep that seemed not to be moving. My father explained that they were sarcopoteriums, and that if you get stuck, you can always spread a blanket and sleep on them. But where are we? Samaria. Once my mother told me it is not enough to lay on the backseat, but that it is better to lay down on the floor. Why? Dad got lost, we accidentally went into an Arab area and it’s nighttime.

The Arabs were everywhere but were hardly seen. We sometimes saw them in the fields while we were searching for turtles or for pieces of wood for our Lag B’Omer campfires. What’s this area next to the garages? A refugee camp. What does that mean? People who live in mud houses. What is Anata? Next to Anatot. Why does the sign have English on it? Because they are Christians. Where is Hizme? After the Bneh Beitcha neighborhood.

Their homes were easy to recognize because they were surrounded by land, and the roofs had antennas in strange shapes that reminded me of the Eiffel Tower. The exterior walls were not prefabricated, and were padded with bruised stones that stuck out like in old Katamon. At the front were stranded trailers and buses with no company logos, some of which had long ago been transformed into biotopes of weeds. Their dogs belonged to no one in particular, barking things that their owners wished they could yell. Here and there, a cat could be seen licking a diaper, and every few years we would see a group of teenagers from our neighborhood running away from the Arabs with a stolen donkey. He would eventually be tied next to the supermarket for everyone to see. Once he was even tied to a sukkah at a nearby park, and at some point he disappeared.

On Yom Kippur, some of the more daring Arabs drove down our neighborhood’s main thoroughfare. We waited for them with rocks, since they interrupted us playing soccer on the road. The one time I worked up the courage to take part in the ceremony, I picked up a dry clod of earth from the traffic island on Moshe Dayan Boulevard and threw it at the Arab’s trunk. The car screeched to a halt, a police officer stepped out and bellowed: “What are you doing, kid?” before driving off.

Nissim never came to visit us in Pisgat Ze’ev, but Rafael “Raful” Eitan, a leading right-wing politician, did. If the year 1992 had a poster it would look like this: Raful standing in the center of the street, his back toward the terraced apartment buildings, the valley in front of him, in the background the theme from the Barcelona Olympics plays. Raful speaks truth to power, my father said, while nodding toward the television.

From the moment I discovered he had voted for Raful’s party, Tzomet, I developed an urge to start delivering my own truisms in my father’s vicinity, all in order to hear him shoot back with the same affirming “Exactly! Exactly!” he would often exclaim while watching Raful’s interviews. If we give them guns, they’ll end up using them against us, both Raful and I argued (that slogan would eventually become a bumper sticker). For some reason he became upset with me when I told people he had voted Tzomet, even going so far as telling my friend’s dad that “Ofer talks too much.”

My father promised the following things: never will everyone withdraw their money from the bank on the same day; parents start a savings account for the children when they are born, so that when they grow up there will be tons of money there; our national team has great defense, they won’t let Colombia score a goal; and we will never be removed from here, even the Arabs understand that. They want us to leave the territories and evacuate all the settlements, but we are not a settlement. We are something else. Both the Americans and the Europeans say so. And anyway, there are already 10,000 people in this neighborhood, and if you include Neve Yaakov and Gilo and the French Hill and East Talpiot that’s nearly 50,000. Everyone knows that’s unrealistic.

The difference was clear: settlers wore sandals and button-down shirts even when they played basketball, and they always had Israeli flags on their roofs. We wore sandals only when hiking through water, our button-downs were saved for the Passover Seder, and we hung our flag from the window of the Mitsubishi.

My mother had friends who thought we lived in a settlement, but she did not stop having coffee with them, because who else could she drink coffee with? Those who did not know my parents thought they were leftists because they did not keep Shabbat or keep kosher, they never had sweets in their homes, and they traveled to strange places like Wales without an organized trip.

Once at an ATM in Ramat Eshkol, after she bargained with the Arab woman who sold prickly pears and got her down to eight shekels, my mother let me punch in the secret code and select the amount. At a certain point, the elderly woman behind us got fed up with waiting and yelled: “Come on, you Ratz folks!” referring to the left-wing predecessor of today’s Meretz party. My mother laughed. They liked that people thought they were something they were not, and when my father was assumed to be Ashkenazi, he would push his glasses toward his face and say: “Pure Sephardic from the Carmel.”

The Arabs in our homes

Like everything in the army, our neighborhood was divided into three sections: families who moved from Neve Yaakov and were considered to be upwardly mobile; young couples who were looking for a more bourgeois lifestyle; and families with many children, who were deemed “gutter kids” and walked around in phosphorescent sweatpants a few sizes too small. Sometimes they were called Arabs, and the harshest among us even organized a boycott against them, laughing at one of the fathers who would make a fool of himself on the bus. Only years later, thanks to Israeli social activist Daphni Leaf, did I learn to give them names: welfare cases, schizophrenics, public housing.

We also moved from Neve Yaakov. My father refused to sell the apartment to Arabs despite the fact that he had offers. He wanted to protect the neighborhood from an Arab invasion but did not know how to put it into words (in Jerusalem we only have the term Hithardut, for when ultra-Orthodox Jews begin moving into more secular neighborhoods). The Arab who seemed to be the most serious buyer sat in our living room and claimed his name was Yosef Hatib, but they asked to see his ID it said Yousef Khattab. My father, who did not like the fact that he had pretended to be Jewish, canceled the deal.

I was already 24 when Israel pulled out of Gaza. I asked my parents what they would prefer in the event that we too would be evacuated: would they leave the home to Arabs, or raze everything? She said it would be a pity to destroy it all, while he calmed me down, saying it won’t happen. The Arabs have made peace with neighborhoods like ours. That’s how it is when you annex immediately.

I tried to imagine Arabs living in our home in our stead. Will they also leave the bathtub running on nights when there is snowfall so that the pipes don’t burst? Will they write the name of every room in Arabic next to the switches in the electrical cabinet? Will they also have a timer for the water heater? Do Arabs even use crawlspaces?

We’ll come visit once every few years. Out of nowhere, we will tell them that we once lived here, asking if we can take a look around, for the sake of the children, and mention that the smell in the stairwell hasn’t changed a bit. They’ll say, come, enter, and offer us coffee. You put the kettle on the table, interesting. We put it on the counter. It’s nice that you left the grapevine. Yeah, they’ll respond, it really produces strange grapes, too small.

A representative from their family will accompany us on the tour like a guide in the White House who makes sure no one steals any candlesticks. They’ll describe how when it rains there forms a giant puddle in the bend around the building, and that their youngest child almost slipped there last winter. Of course, I’ll say, it’s because of the terrible planning, and they will talk about how they changed all the street names, and I’ll say that they should really name the bend Sabah Path, since it is exactly where his cliff used to be, and they will say it’s getting late.

The hypocritical Left

They’ve been living in the city for 50 years, but they are still Haifa born and bred. They refer to the Jerusalemites as “them,” and laugh at the fact that they use plastic bags as a purse while running errands. Everyone who is like my parents has long moved to the suburbs of Jerusalem to Tel Aviv, only visiting the city for a little taste of culture. But my parents prefer Freij’s supermarket in Shu’afat over the big malls, and for the past two years have been taking Arabic lessons. This is exactly why the Left is hypocritical, says my mother, people who love Arabs but are afraid to speak with them.

Arabs are sitting in our living room at this very moment, drinking lemon verbena tea and eating tahini cookies. My father says that the man is a doctor in Hadassah Hospital and his wife is a social worker. He wonders whether he should sell to the Arabs. What has changed? He sees things differently. How different? Different. It’s also a matter of age. They are moderate Israeli Arabs, educated, they want an apartment where they can raise their children. So why not?

It’s interesting that you’ll give the house to Palestinians. They’re not Palestinians, they are Israeli Arabs from Nazareth. He is a doctor and she is a social worker. They don’t want an Arab neighborhood, just a good area with good schools for their children and a light rail to bring them to Hadassah. Did you ever think that not all the Arabs want to be called Palestinians? Maybe they like living here? Maybe they don’t want to live under Arab rule? Maybe they want a community center and activities for their children? Oh, before you go, there’s a bag in the bomb shelter with your old army uniform and your shoes. What should I do with it?

Ofer Matan is a writer for Yedioth Ahronoth. This article was first published in Hebrew on Local Call. Read it here.