A new law aiming to silence the Muslim call to prayer is just one manifestation of efforts to erase Palestinian culture and identity. But language and heritage aren’t so easy to disappear.

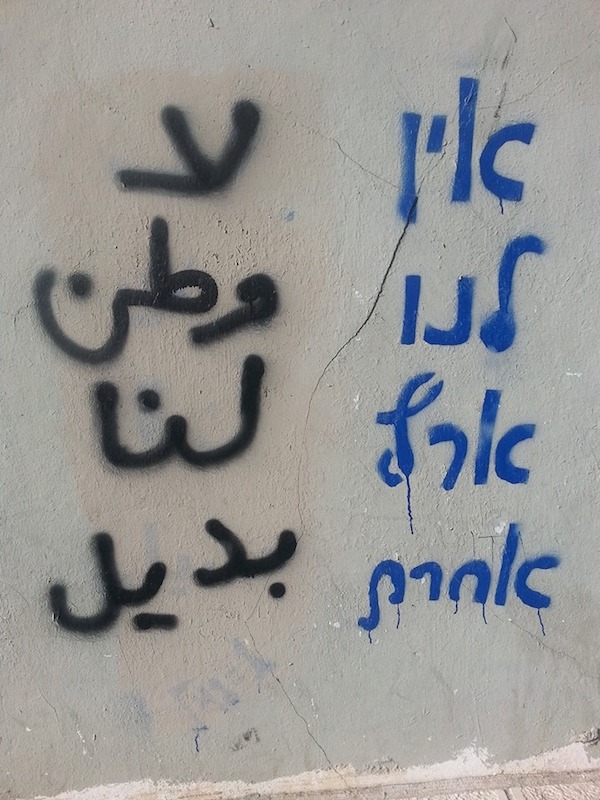

There is a building on Michelangelo Street in Jaffa, near where I used to live, which for a while featured the sentiment “We have no other country” graffitied in both Arabic and Hebrew, side by side. One day, the Arabic was painted over, presumably by the municipality, leaving only the Hebrew. Almost immediately, someone restored the Arabic. It was painted over again. This pattern continued until a friend publicly asked the municipality why her taxes were being used to such obviously racist ends; by the following morning, both languages had been painted over.

This sad waltz, and all that it signifies, is a useful parable in light of the so-called muezzin law’s reappearance in Israel’s parliament this week. The bill, a noise restriction policy carefully designed to partially silence the Muslim call to prayer in Israel, took another step forward on Sunday when a Knesset committee voted to advance the legislation toward becoming law.

Although the intended target of the law is tucked away in the Trojan Horse phrasing of “noise caused by loudspeaker systems in houses of worship,” the bill specifies that the restrictions only apply between 11 p.m. and 7 a.m. As Adalah — The Legal Center for Arab Minority Rights in Israel points out, mosques are the sole places of worship that broadcast calls to prayer during these hours.

This rubbing out of Arabic — and above all Muslim — culture, language and memory in the Israeli public space is as much part of the assault on Palestinian history and presence as home demolitions, expulsions, occupation, and siege. It may be the quieter arm of the enterprise, but it works just as effectively to undermine the foundations of Palestinian society.

The effort to dismantle Palestinian national identity and memory takes various forms. At the government level, alongside recurring attempts to pass some version of the “muezzin law,” initiatives seeking to demote Arabic from its status as an official language of Israel surface every year or two. The so-called “Nakba Law” gives the state authority to reduce its funding for any institution that treats Israel’s Independence Day as a day of mourning. Culture Minister Miri Regev has threatened to pull funding for institutions that she deems to be giving a “platform” to Palestinian narratives.

At the municipal and social level, road signs pointing to Jerusalem often appear without the city’s Arabic name, Al-Quds, instead featuring the hybrid word “Urshalim” in Arabic letters. It is not uncommon to see road and street signs throughout the country on which the Arabic lettering has been defaced or obscured entirely. Tourist maps have recently appeared in Jaffa and Jerusalem that reduce Palestinian heritage and culture in both to the barest minimum.

The cultural vandalism at work here — whether systematically at the hands of the government, or randomly at the hands of a certain subset of Israelis — is unabashedly racist. But as with any prejudice, it’s worth going below the surface to interrogate it a little further; to that end, one recent episode is particularly instructive.

Last summer, Israel’s Army Radio broadcast an educational program about the Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish, featuring one of his most noted poems, “ID Card” (which contains the famous line, “Write it down! I am an Arab”). Right-wing populists such as Miri Regev and Defense Minister Avigdor Liberman immediately lashed out with threats of defunding, sackings and more, the latter throwing in a parallel to “Mein Kampf” for good measure.

To a certain extent, this was Regev and Liberman doing what they do, but there is more that informs such knee-jerk reactions. Darwish and his work haunt the Israeli imaginary; his status as Palestine’s de facto national poet aside, the themes in Darwish’s writing — exile, trauma, dispossession and the longing for return — are searingly resonant for Israeli Jews. But they are presented as part of a narrative that places responsibility for those experiences at Israel’s feet. This is unconscionable for most Israelis, because it threatens the state’s founding mythology of total national unity and tireless heroism as a response to near-obliteration. This fantasy, which has been preserved for nearly seven decades, elides the expulsion of Palestinians — the Nakba — that was integral to Israel’s state-building project; Darwish’s work restores it front-and-center.

This fear is not limited to concerns over the legacy of Israel’s founding. For many Israeli Jews (and Jews in the Diaspora), acknowledging the existence of a Palestinian collective consciousness is part of a zero sum game, one in which allowing Palestinian memory to be seen and cultivated would deal a mortal blow to Jewish-Israeli society and its own narrative. Sociocultural territory is, for the dominant Jewish majority, as fraught and existential an issue as physical territory.

The allergy towards signs of Arab presence extends beyond Palestinians. The institutional racism faced by Mizrahim, even if it is not codified to the extent that anti-Palestinian racism is, marks the intersection of two discrete, but related, fears held by the Ashkenazi hierarchy: that over their security, and that over the integrity of their (white, European) identity.

There is also an acute fear among the powers that be that these two groups — Palestinian and Mizrahi — will bond in solidarity, a fear that provokes some of the most irrational reactions of all: look no further than a recent Israeli movie awards ceremony, during which Regev — herself Mizrahi — went into orbit after Palestinian rapper Tamer Nafar and self-identified Arab Jew Yossi Tsabari performed on stage together, with the latter reciting lines from Darwish’s “ID Card.” The sight of an Israeli Jew standing next to a Palestinian and proclaiming, “Write it down! I, too, am an Arab,” was apparently too much to bear.

For now, the attempts at erasure continue, and the Knesset will vote in the coming days on whether to silence a song of this land. But for what it’s worth, the graffitied Hebrew and Arabic slogans, “We have no other country,” remain dotted here and there throughout Jaffa, bilingual, side by side. And that’s the second part of this parable: that a language, alive as it is, the linchpin of national and cultural identity, cannot be disappeared so easily. You can try and cover it over, but — like the identity it channels — it will re-emerge, in new ways, and in new forms. Write it down.