In May of this year, Economics and Trade Minister Naftali Bennett devised a plan to replace port workers with IDF soldiers in the case of a strike. Not only did Bennett’s spin make for a dangerous contribution to the ongoing incitement campaign against port workers, it also fit neatly into the racialized way the majority of Israelis view them.

By Yossi Edry (Translated from Hebrew by Noam Benishie)

“Code Name 1981,” screamed the headlines, revealing Minister Naftali Bennett’s plan: “The military is to replace port workers in the case of a strike.” It was the boldest yet step in a well-organized and orchestrated campaign waged by politicians and senior officials at the Ministry of Finance against Israel’s port workers. The timing, too, was carefully chosen – several days after thousands took to the streets to protest against the harsh budget drafted by Minister of Finance Yair Lapid, Bennett’s political ally and friend. This measure is unique in neither its functionality, which is virtually non-existent (who exactly is going to manage the complex operation of the ports? Unqualified regular service soldiers?) nor by its dubious legal status. Its uniqueness stems from the employment of the most powerful tool in the Israeli collective imagination – the IDF. The “people’s army” as a means to fight the enemy of the people from the port is an unprecedented practice. IDF soldiers, as everybody knows, are the most popular group among most Israeli citizens, therefore using them secures an automatic blind sympathy, and nobody knows that better than Bennett.

Bennett’s preposterous spin made for a dangerous contribution to the ongoing incitement campaign against against port workers. He further pursued the matter on his Facebook page, where he laid the blame for Israel’s high cost of living on the port workers, their inefficiency and corruption. This attack comes as no surprise. You may notice that the verbs most popularly employed in the Israeli discourse into the port workers union are “crush,” “tear down,” and “break down.” These are violent verbs, usually reserved for the “Palestinian enemy.” Bennett has realized that Israeli port workers’ image is currently at a low, making it the right time to strike; yet he is not alone. Minister of Transportation Yisrael Katz, who felt the fame of ramming port workers snatched from his hands, jumped on the bandwagon and joined the vilifying rampage waged against the workers. He was quick to announce that he had no fear of the “militant” port unions, and vowed to face them intrepidly. This is a further reiteration of a rhetoric borrowed from military terminology, designed to portray the opposition as terrorists and divert discussion from any social-economic discourse.

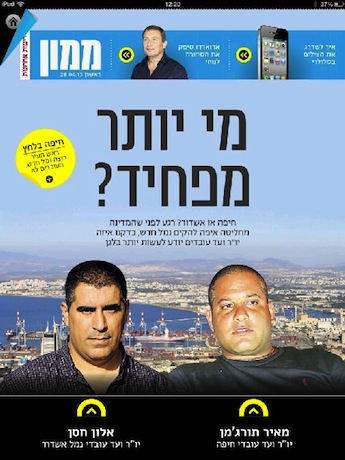

There is nothing new about this violent tactic employed against port workers. As early as the 1960’s they were referred to as “terrorists,” having had the gall to fight for their rights in the workplace, while their Mizrahiness served as a powerful labeling tool, setting them apart from other trade unions in the Israeli economy. Israeli discourse in this context has since become more subtle, taking on board the issue’s highly sensitive status, yet the question remains: what part does the Mizrahiness of the port workers’ mouthpiece have to play in shaping attitudes towards them? Is it all too easy to turn port workers into a “clan” – a concept laden with negative connotations in the Israeli discourse, or rather into a “bunch of Arsim” (a racialized and derogatory term for low-class men), perceived as they are to be a predominantly Mizrahi body of workers? I think the answer is definitely yes. A predominantly Ashkenazi body of workers would probably not be portrayed with the very linguistic terms associated with the Mizrahi public. The unapologetic conduct of Haifa and Ashdod ports’ trade union leaders, Meir Turjeman and Alon Hassan, compounds this brute image, which is in turn fully exploited by people with interests.

The fact that according to the 2012 annual report by the government companies authorities (PDF), the Israel Ports Company netted 218.5 million NIS in 2012, compared to a mere 86.9 million NIS in the previous year, rarely gets mentioned (to say nothing of crediting at least some of this success to the much-maligned workers).

Even the great outcry raised against their “inflated” salaries and “wage frenzy” is taken out of any rational context. The port pilots starring in the lists of top public sector earners perform a duty equivalent to that of airmen. A port pilot is a highly experienced captain, physically navigating foreign vessels into port upon their arrival. It is a job requiring experience, skill and composure. Port pilots are rewarded with high salaries, as they usually receive this position in their 50s, after a long tenure. The outcry aimed at the supposedly high salaries earned by fork-lift and crane operators is also ludicrous, given the exhaustion and grind involved year-round in this physical labor. The lion’s share of these operators salary comprises premiums and overtime, and workers are encouraged by the port’s management to increase their output as part of the reorganization reform. Yet when they work extra hours and are rewarded for it, they are once again attacked. The infamous steak coupons were another part of the management’s attempt to incentivise workers – and this step indeed yielded positive results. Labor productivity increased by millions of NIS, yet this bonus was revoked following public outcry. In reality, the ports have a limited number of long-tenured workers who are soon to retire, thus significantly lowering the average salary. However, the leading financial press does not find this fact interesting enough.

The Israeli public discourse, generated largely by the financial press, deems it inappropriate for blue-collar laborers to earn decent salaries, as befitting their long experience and the hard, dangerous work they perform. At the same time, a salary of tens of thousands of shekels earned by a news anchor (a position that until recently belonged to Minister Yair Lapid), is deemed legitimate and reasonable. It is another instance of the absurdity at play in the Israeli society and the collective change of mind that the country has undergone. “Hebrew labor,” so highly valued around here (or so they liked to think…) and so eagerly and proudly cited, is rendered even more insignificant when Mizrahim from the ports are concerned. Furthermore, it is important to understand that any move to privatize the ports involves great risks, concealed from the public. First of all, the big bad strike wolf doesn’t spare privatized ports; just look at the strike in the privately owned Hong Kong port, which lasted forty days, and ended only recently. Second, and more importantly, a privatized port can turn into a no man’s land in terms of safety. Let me suggest a fictional scenario. The State of Israel privatises its ports. Safety levels drop due to first generation senior staff retiring, replaced by new, inexperienced hands that cost the private employer much less. After a series of deadly accidents a public rage ensues, ending with the state’s decision to nationalize control over the port’s safety services. The very same scenario played out in England’s railway service. It is a move that will lead to a massive use of public funds that could be saved.

I do not argue that Haifa and Ashdod ports are free of deplorable practices such as nepotism, looking out for union cronies or senior staff brute conduct. Yet these are practices the state of Israel has the tools to tackle without reviling a whole group of workers and victimizing them in a campaign to crush what little remains of the Israeli organized labour. I believe it is possible, nay, advisable, to demand that the port workers union show greater solidarity with the disadvantaged workers of Israel and come out of their shell. I don’t deem Alon Hassan the Israeli Lech Wałęsa, yet he is no Al Capone either. The portrayal of him as such, and the portrayal of his workers as a crime family, is an injustice and a huge stain on the history of the Israeli labor market.

Yossi Edry is an M.A. student at Tel Aviv University’s Department of General History. This article was first published in Hebrew on Haokets.