Ellis Kadoorie hoped that by establishing an agricultural school in Tulkarm, he would be helping to educate and improve the conditions of Palestinians and Jews alike. Little did he know it would become a microcosm of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

By Tamar Novick and Arie M. Dubnov

The Kadoorie Agricultural School holds a special place in Israeli national memory; a second home for figures like the poet of the 1948 war, Haim Gouri, the future generals Yigal Allon and Yitzhak Rabin, and many of the Palmach generation, the school is seen as the spiritual soil from which sprouted the mythological Sabra. “Kadoorie was more than just an educational institution,” wrote Allon in his memoir; it was an “educational and life-forging structure,” which molded the character of its students. With the passing years, many students became leading commanders of the Israeli Defense Forces in its first years, and their manners, clothes, speech acts, and celebrated “straightforwardness” supplied the associations and images through which the ideal of the “1948 generation” was constructed.

This generation’s presence in Israeli society only grew stronger as new generations followed. Yosef Milo, who directed the classic Israeli film “He Walked Through the Fields” (1967), pushed this point home in his take on Moshe Shamir’s novel, which tells the story of a paratrooper who upon his return from the battlefield in the Golan Heights, is seen paying a visit to the principal of Kadoorie Agricultural School on his way home to his kibbutz. The new Uri, a brave soldier of the Six Day War, is shown standing in the principal’s office, looking at a wall covered with photos of famous graduates, including that of the old Uri, the mythological Palmachnik who died at war. The choice of Assi Dayan, the son of the one-eyed general Moshe Dayan, for the role of the conflicted and feisty Uri, was not accidental, and established a connection between the generation of the sons and that of the combatant-fathers. The choice of the Kadoorie School as the filming site was also significant. This cinematic act concluded, in fact, the process of turning the school into what historian Pierre Nora calls “a site of memory” (lieu de mémoire) — that is, a space or physical object that codifies, sums up, and anchors national memory.

Rothschilds of the East

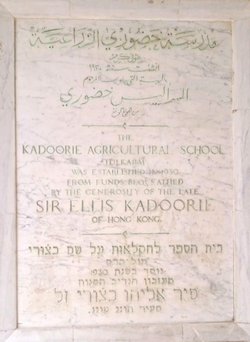

Yet only very few Jewish Israelis know about the existence of a twin school, also named after Kadoorie, located in the West Bank city of Tulkarm. Both schools were established with the aim of training Jews and Arabs in modern standards of agricultural work. Such an idea was not novel at the time, as already it had already been implemented at the Mikveh-Israel agricultural school. Nevertheless, it gained new prominence thanks to the Jewish-Iraqi philanthropist Sir Ellis Kadoorie (pronounced Kh’adoorie), who on his deathbed bequeathed a large sum of money to the British government for the purpose of constructing “a school or schools” to be built under his name in Palestine or Mesopotamia (that is, modern Iraq), “as the British government sees fit.”

The story of Ellis Kadoorie and his family has yet to be researched and fully told. In brief, he was part of the Jewish elite of Baghdad, coming from a family of merchants who prospered thanks to an extensive network of commerce established during the nineteenth century, in the midst of the Opium Wars, and which connected Mesopotamia, Hong Kong, London, Kolkata, and Shanghai. Through marriage and business, the Kadoorie family was linked to the famous Sassoon family, which also played a major role in establishing gradual control over export routes from East Asia to the Levant and Europe. For many reasons, these two families were considered the “Rothschilds of the East.” Strong ties between imperial commerce networks — along with convoluted yet unmediated economic relations based on blood-ties and religion — undoubtedly explain some of their seemingly miraculous success.

The famous descendants of these two elite families — be it member of Parliament Baronet Albert Abdullah David Sassoon, poet Siegfried Sassoon, still known today for his memoir of pre-war Britain and halting friendship with Robert Graves, historian and researcher of nationalism Elie Kedourie, or journalist Rachel Sassoon Beer, the first woman in Britain to become an editor of a national newspaper (in fact she was editor at both The Observer and The Sunday Times) — all adopted the manners and world views of the British establishment and cultivated an anglophile — and at times, even pro-imperial — agenda.

Many members of these families converted to Christianity, while others, such as Freha (Flora) Sassoon and her son, collector and researcher David Sassoon, proudly held to their Jewish identity in its orthodox form. To a significant extent, their various networks represented an extraterritorial imperial reality, born out of the role of the British Empire as a platform for economic and cultural prosperity. As such, the imperial networks allowed commercial life to align with a common Jewish practice: going beyond the local and the national in establishing extraterritorial ties between various Diaspora communities.

Unlike his brother, Eliezer Sailes Kadoorie, a businessman and philanthropist who supported the Zionist cause, Ellis Kadoorie was not motivated by pro-Zionist sentiment so much as by a profound belief in the ability and responsibility of the Empire to educate and improve the conditions of local people: Muslims, Christians, and Jews alike. His legacy, however, left much room for negotiation. Where would the schools be built, what would be their character, and who would be the students? The Zionist offices in London exerted pressure, and the entirety of the bequest was directed to Palestine (rather than Mesopotamia), which was then governed by Lord Herbert Samuel. Yet this only opened the door to more wrangling, with a fierce debate arising as to whether there should be one joint school for both Jewish and Arabs students or two separate schools?

As opposed to Samuel, who aspired to establish an integrative school, Jewish members of the government promoted a plan that would exhaust the funds bequeathed through construction of three schools that would accept only Jewish students – in Jerusalem, Jaffa, and Tiberius. These schools were to be planned by Jewish architects, and constructed according to the rules of “Hebrew Labor” (that is, it was built by Jews). The debate ended in late 1925, when Samuel’s successor, High Commissioner Herbert Plumer, decided to establish two separate agricultural schools — one for Arab students in the Tulkarm area and the other for Jewish students at the foot of Mount Tabor. Plumer argued that he was following “the demands of both populations.” This precedent — separation along religious and ethno-nationalistic lines — was a reflection of the tendencies that would strengthen in the years to come. In this sense, 1925 might be called “year zero” of the so-called Jewish-Arab conflict.

The geographical location of the Arab school is not devoid of historical significance. The Tulkarm subdistrict, which spread out from hills of Samaria to the coast of the Mediterranean Sea (the Sharon area and current day city of Netanya), had been renowned for many generations for the quality of its agricultural products. Even the name (Tulkarm means “the long vineyard,” in Arabic), which is mentioned in the Talmud, hints at this agricultural fertility. Yet the fields of the city had also been the site of military confrontation in the not too distant past. The Battle of Tulkarm, which took place on September 19, 1918, and in which the British XXI Corps’ 60th Division confronted the Turkish 7th and 8th Army, was fought on what would later become the Kadoorie School. Three Indian infantry brigades engaged in this battle, mostly consisting of Muslim and Sikh soldiers, accompanying the forces of General Edmund Allenby on their way to Palestine. The British monument commemorating those lost in the battle is now situated within the school’s grounds, and remains a silent reminder of the violent events. Notably, it includes information about the Turkish troops who died in battle, along with the soldiers of the Sikh units attached to General Allenby’s troops.

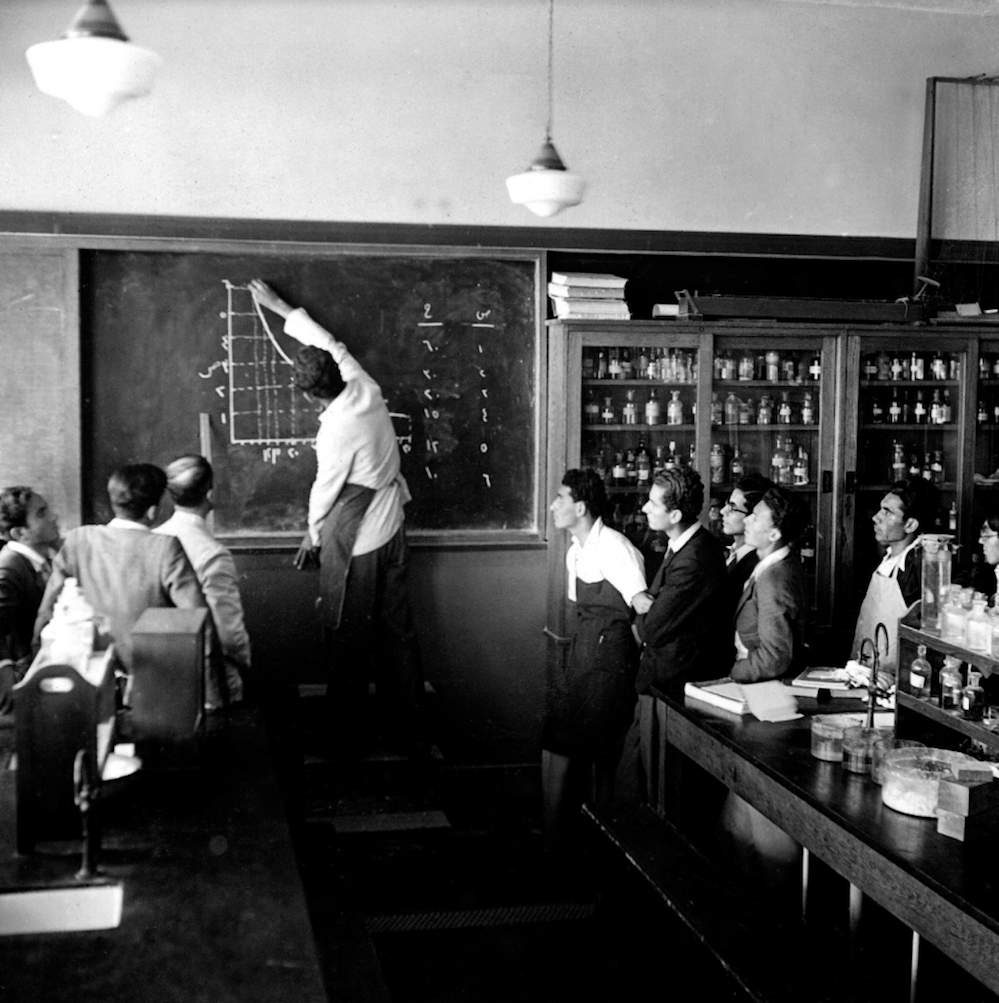

The idea of establishing agricultural schools fit well with the British Empire’s plans for colonial development. The schools became central sites for disseminating models of intensive agriculture and mixed-farming. The Tulkarm Kadoorie school, in this sense, was no less important than the Jewish one: governmental support for training both Arab and Jewish farmers, together with agricultural guidance supplied by the experimental stations at Acre and Nablus, were meant to help the British government create a local elite. In particular, the plan was to nurture agricultural professionals and experts (all of them men), who would return to their homes upon graduation and lead their communities in agricultural and economic progress.

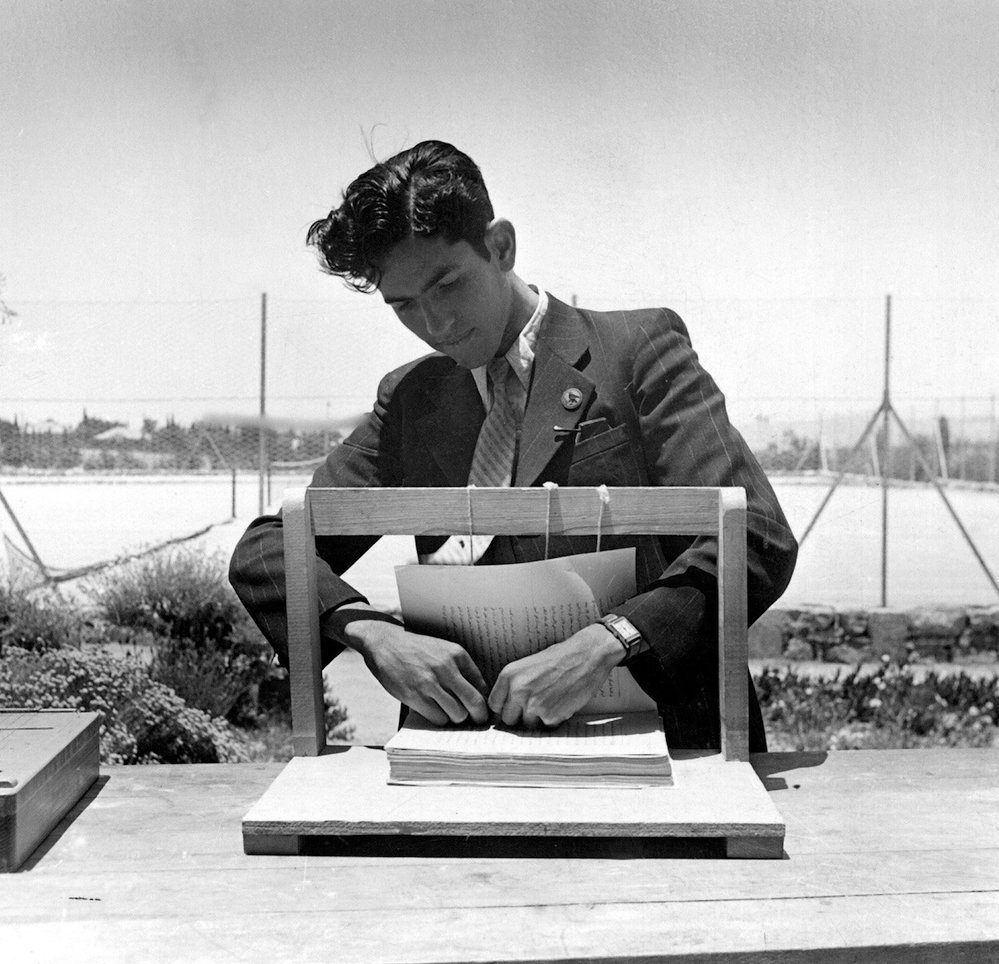

The school opened its gates to students in 1931. A series of photographs, taken by photographer Moshe (Nicholas) Schwartz, gives some sense of the agricultural practices at the heart of the Tulkarm Kadoorie School’s training program. That Schwartz’s bosses – the governmental Palestine Information Organization (PIO) – charged him with producing a series of photographs documenting everyday life at the school suggests that it was viewed as the source for the outburst of modernization in the Middle East.

While few Arab students needed to be taught how to use a sickle, the school took pride in training its students in the operation of tractors and harvesters, of movable-frame beehives, as well as modern dairy. At the same time, the Tulkarm school was embedded within a larger plan to develop the regional road and train system in order to create tighter connections between the city and the agricultural hinterland, allowing for agricultural produce, especially milk produced by the cows of the school and fruit in its orchards, to arrive quickly on the coast and at the port in Jaffa. From Jaffa — the main economic route of the region — the produce would be sent to markets across the Empire.

The rapid and successful materialization of the vision of an agricultural school notwithstanding, challenges and problems beset the school from the start. The first principal was the British H. M. Heald, an appointment that stirred protest among the students and led, so it seems, to his replacement by Izz Ad-din al-Shawa (1902-1969). Al-Shawa was one of famed Palestinian educator and poet Khalil al-Sakakini’s childhood friends and a graduate of the universities of Beirut and Cambridge, who later became the regional officer of Haifa and Jenin.

Other problems emerged as the chemist hired to survey the soil composition around the school determined that it was problematic and heavy, and could only be used for growing fodder. Later, it became clear that the various plans for road construction, fencing, and changing the route of the train ran up against the spatial logic of the school (and would interrupt the privacy of the students bathing in the school’s swimming pool). In addition, the school’s management became bogged down in arguments over distribution of limited financial resources, while various disputes broke out between the management and the government with regard to the ownership of the school’s agricultural fields and their leasing. The temporary definition of some of the land as “forest reserve areas” allowed the government to ban settlement, agriculture, or grazing. This legal mechanism emerged as a common way of changing the use of land and its ownership, and the same areas were later rezoned, ultimately becoming the property of the Jewish National Fund.

But the major challenge faced by the school was its irregular operation. Studies were frequently interrupted for security reasons, or in response to “events,” as the government called the Arab Revolt of the years 1936-1939, which saw the school shut down for extended periods of time.

On many levels, the harsh British reaction to the revolt was tied to the fact that both the Arab and the Jewish schools were widely perceived as governmental institutions. Students of both schools, for example, protested, separately but in parallel (1935), over the fact that the management favored British interests over the needs of the students. In the wake of the revolt, such tendencies became radicalized, and the schools themselves turned into centers for attacks and arson. The schools diverged in those turbulent days. On the one hand, Yitzhak Sadeh began recruiting young people, including the Jewish Kadoorie students, to “fields platoons” (Plugot Sadeh), which he established with the support of the British government as part of the Zionist pre-state Haganah paramilitary force. On the other hand, during that period, Izz Ad-din al-Shawa, the second principal of the Arab Kadoorie School, joined Fawzi al-Qawuqji’s Arab Liberation Army.

Government officials began to treat activities within the Tulkarm school with great suspicion. One surviving report describes a fire breaking out in the school during the revolt, and notes the refusal of Mandate officials to purchase new equipment — chairs and desks — to replace those that had been burned, according to them, as acts of resistance and in contempt for the government. In addition to such attitudes, the British military “occupied the school” whenever it was deemed necessary. Other aggressive mechanisms of policing and control found their way into the school grounds, and were later adopted by the IDF. In 1937, Izz Ad-din al-Shawa fled and lived in exile in Syria and Iraq until 1947. In 1948, he returned to Palestine to join the war effort. Following the Arab defeat he escaped to Lebanon, where he lived as a refugee until his death.

After 1948 the school lost land that lay on the western side of the ceasefire line, which then became a part of the territory of the State of Israel. The school continued to operate, however, as a college under Jordanian rule. Soccer players from the teams of both schools – Arab and Jewish – no longer competed, as they had done in earlier days. Instead, as can be seen in photos from that period, soccer matches were held between the Tulkarm Kadoorie team and other teams from the Arab world. Among the graduates of the institution are ministers in the Jordanian and Iranian governments, including Adnan Badran, a Jordanian scientist who was briefly prime minister. Abdullah Yusuf Azzam (1941-1989), a member of the Muslim Brotherhood, who went on to become one of Al-Qaida’s architects, was also among its graduates.

The college continued to operate under Israeli occupation. In 2007 it was granted the status of university by the Palestinian Authority, making Kadoorie, with its 7,000 students, the little sister of larger Palestinian universities such as Al-Quds, An-Najah, and Birzeit. The Oslo Accords did not help the prosperity of the college; in fact, as a result of the new division of territories into Areas A, B, and C, the college’s management was forced to deal with an artificial separation between the campus’ buildings area, which fell under Area A (under full Palestinian control) in the agreement, and the university’s agricultural lands, which became Area C (under full Israeli control). The British war monument, once positioned in fields that seemed to extend as far as the sea, is now close to an IDF checkpoint and the West Bank separation barrier. The cars roaming the nearby Israeli Route 6, adjunct to the barrier, can be clearly seen from the fields.

Since 2002 the IDF has used areas expropriated from the campus as a training area and shooting range. The proximity of the shooting range, and the consequent noise levels in the classrooms, have been a source of constant friction between the students and the military, often ending in military attacks, as well as damage to property. Incursions by IDF forces into the campus became a common sight in 2015, when the campus was attacked 130 times, according to university faculty. One of the absurd turns of events during this period took place when university personnel tried to decrease friction by constructing their own separation wall between soldiers and students who throw stones. Military forces banned these attempts, and confiscated the bulldozer that had been used for the construction.

In April 2016 Israeli academics belonging to the organization Academia for Equality launched an international campaign that demanded an en to military training on campus. Shortly after a solidarity visit to the campus by Israeli academics, the IDF announced that the shooting range would be removed from campus grounds. The fields were quiet again, but only for a brief period: two months ago, on November 17, 2016, Kadoorie University faculty members reported another IDF night incursion on campus, in which documents were confiscated, the computer lab doors were broken, and the security cameras’ footage was confiscated.

Regardless of political turmoil, the Kadoorie family’s business continued to flourish and branch out. Their commitment to philanthropy and aid in agricultural training did not disappear either, but moved to new locations after World War II. In 1951, Ellis’ nephews established an agricultural training farm in order to help Hong Kong farmers battle economic hardships brought about by war. The Kadoorie family’s Botanical Gardens and Agricultural Farm in Hong Kong blossoms to this day, maintaining the tradition of agricultural education of the Kadoorie Agricultural Aid Association. A short drive away is the prestigious Peninsula Hotel, which was established by the family in 1928 and is currently owned by Sir Michael Kadoorie. In the years that followed, the family’s philanthropy was directed to Nepal in an attempt to help retired Gurkhas, as the Nepali units that served in the British Army were called, to make a living as farmers after release from military service. This cooperation continues to this day, and in 2015-16 the family fund donated over 4.5 million pounds for Nepali community aid.

Like the Jewish Kadoorie School, the story of the Tulkarm Kadoorie University is allegorical. The bruised soil on which the small university still stands supplies a piece of shrunken history, a few acres that contain so many of the vicissitudes, difficulties, and hopes of the Middle East of the twentieth century. Ellis Kadoorie’s desire that those who walked through the fields, on both sides, would bring development, modernization and prosperity, crashed against the jagged rocks of reality, where conflict and separation are recurring features. The experiment that failed in Mandate Palestine, so it seems, was then adapted to the Global South. The future of the fields of Palestine Technical University — Kadoorie, however, remains unknown.

The authors would like to thank Ayelet Ben-Yishai, Shira Wilkof, Ofri Ilany, Shay Hazkani, Rotem Geva, Yuval Evri, Haya Bambaji-Sasportas, and Hilla Dayan for their comments and assistance in preparing this article. This article was first published in Hebrew on Haokets. Read it here.