The Palestinian people have become dependent on foreign humanitarian aid to survive, but its adverse effects are strangling their economy.

By Liora Sion

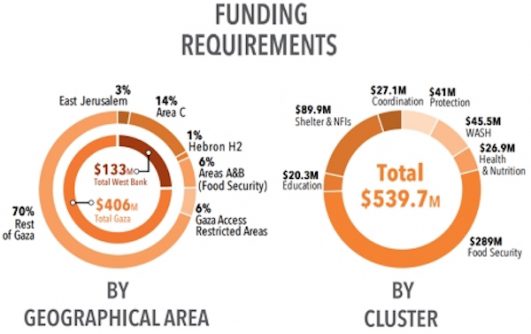

International aid to the Palestinians is very generous. The United Nations is aiming to raise approximately $540 million per year for the five million Palestinians living in the West Bank and Gaza. That’s a lot of money when compared to sums raised for other countries in crisis. For example, take Afghanistan, where the UN hopes to raise $437 million for the 34 million citizens of the country, despite the enormous difficulties it faces. In Iraq, a country in desperate need of rehabilitation, the UN seeks to raise $550 million for a population of 37 million. When compared to African countries such as Burundi ($113 million in aid for 10 million people) or Cameroon ($304.5 million for 23 million people), the gap is even more alarming.

Ironically, despite the vast sums, humanitarian aid doesn’t just help the Palestinians — it also harms them. Since the signing of the Oslo Accords in 1993, the occupied territories have seen a steady economic decline and a rise in unemployment. These phenomena are tied, of course, largely due to the IDF’s closures and checkpoints, which have dismembered the West Bank and prevent both people and goods from moving about freely. Humanitarian organizations, however, also play a role.

Most humanitarian aid is not invested in developing the Palestinian economy. According to the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), $289 million out of $539.7 million is earmarked for food security for Palestinian residents of the occupied territories. Another $20 million is earmarked for education, $26.9 million for health, $89.9 million is for temporary shelters for Palestinians whose homes have been demolished, $27 million for coordination, $41 million for protection, and $45.5 million for hygiene and drinking water sanitation. Most of the money is earmarked for the residents of Gaza, who face the greatest hardships.

These sums ensure that Palestinians do not die of hunger, that they receive a good education, and have a functioning health care system. It is surely more than what residents of other countries receive. Yet these funds are not earmarked for creating new jobs or building infrastructure. The Palestinian Authority is the the main source of income for residents of the occupied territories who do not work in Israel or for one of the UN agencies. Moreover, a recent report by the World Bank reveals that these funds are no longer are sufficient to raise the standard of living in the West Bank.

The donor countries are part of the problem. Since the end of the Cold War, states have preferred humanitarian aid over development funds as a means of influencing international politics. Humanitarian aid is not an end in and of itself, but a tool to solve conflicts and promote state building. As such, it is dependent on the interests of the donor countries.

The power struggle between former Palestinian Prime Minister Salam Fayyad and President Mahmoud Abbas gives us a glimpse into how aid is used a political tool. Fayyad sought to build functioning state institutions and fight corruption. He won the support of the West, but the U.S. gave its backing to Abbas. Despite the latter’s corruption (which was also enabled by the U.S.), Abbas served American and Israeli interests by maintaining stability in the occupied territories and by acting against Hamas.

The Palestinians receive a relatively large amount of aid in exchange for their adherence to the illusion known as the “peace process.” Many countries are willing to donate money to educate young people for democracy or gender equality but not to the productive sector. Thus aid only increases Palestinian dependence on the international community. The rampant corruption in the Palestinian Authority makes matters worse. Humanitarian aid organizations have helped create a new class of PA employees, police officers, businessmen, and NGO workers who are dependent on international aid for their livelihoods.

Even when donor countries are willing to fund economic initiatives, no one asks the Palestinians what they need — despite the fact that the Palestinian population is relatively educated and skilled. The experts, the volunteers, the technology, and the work materials are often imported from the donor countries, which get a return on part of their investment. The European Union, for example, demands that all necessary equipment for its initiatives be imported from Europe. The increase in international aid workers not only drives economic activity — it also has negative consequences, including a meteoric rise in the cost of rent in East Jerusalem. Aid workers are able to pay large sums for housing that most Palestinians simply cannot afford, excluding them from the rental market.

Thus the Palestinians have become passive, frustrated, and desperate recipients of international aid. Anger at the situation, which was initially the domain of the elites, has spread in Palestinian society, and it is no longer uncommon to encounter protests against aid agencies such as UNRWA, USAID, or the European Union.

The Palestinians are between a rock and a hard place. On the one hand, they need the aid to survive. On the other hand, aid limits both Palestinian society and its economy, makes them dependent on foreign assistance, makes them accustomed to a lack of productivity, and ultimately strangles them.

Liora Sion has a PhD in sociology from Amsterdam University and is a research fellow at the Forum for Regional Thinking, where a Hebrew version of this article was first published. Read it here.