A new poll shows that among Israeli settlers, a striking 74 percent say that conditions in Israel these days are good or very good. The same cannot be said for their Palestinian neighbors.

Late Thursday night, the Israeli security cabinet voted unanimously to approve the establishment of a new West Bank settlement to be populated mainly by former residents of Amona, an illegal Israeli outpost ordered dismantled by the High Court of Justice. The cabinet’s decision effectively means that Amona was not truly dismantled, but rather put on hiatus before being reestablished about 20 kilometers away.

In the same meeting, the security cabinet also approved partial and “murky” restrictions to settlement growth. Those constraints are understood to be a gesture to U.S. President Donald Trump’s nod toward a future peace process. In February, Trump told Israeli newspaper Israel Hayom that he did not believe further construction is good for peace, after the White House had released an earlier statement that Israel should refrain from announcing new settlements.

Which of these decisions reflects the future of the settlement enterprise in Israel – expansion or constraint? The new Trump era is still unfolding, but settlers have their own opinion. For them, the future looks bright.

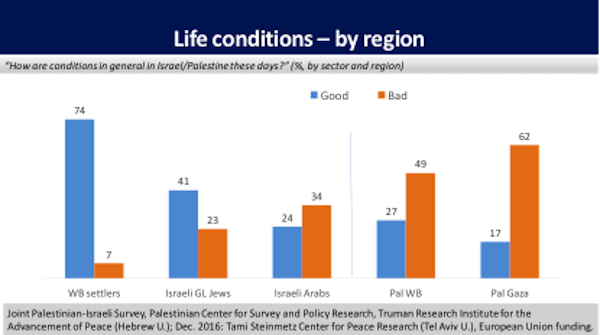

A large-scale survey from December, the “Palestinian-Israeli Pulse” (a joint poll conducted by the Tami Steinmetz Center for Peace Research (TSC), Tel Aviv University and the Palestinian Center for Policy and Survey Research (PSR) in Ramallah, with funding from the EU), for which I lead the Israeli research, found that among Israel’s Jewish West Bank residents (settlers), a striking 74 percent majority said that conditions in Israel these days are good or very good.

This simple question tells a major story. The settlers emerge as the most satisfied people between the river and the sea. Israeli Jews who live inside the Green Line find life much harder: just 41 percent of them say conditions are good in total. Twice as many West Bank settlers said conditions are very good, the most positive answer, relative to Jews inside the Green line (31 percent to 13 percent, respectively).

The experience of daily life is starkly divided along ethnic lines: among Arab citizens of Israel, just one quarter of respondents think conditions are good or very good – one third say they are bad in total. The remainder gave a non-committal “so-so” response.

Responses among Palestinians show an entirely different reality. Half of Palestinians in the West Bank think conditions are bad or very bad, as do 62 percent — nearly two-thirds — among Gaza residents. In total, over half of Palestinians say conditions are bad or very bad, and just 23 percent in total say conditions are good. In Gaza this number stands at just 17 percent.

The contrast in responses to this standard question shows clearly who benefits from the 50-year military regime controlling Palestinians, by the admission of those beneficiaries, and who actually suffers. The findings also contain the reality of how general daily life conditions favor settlers above all other Israelis.

But in December – before Trump’s contradictions began to show through – the settler satisfaction probably also reflected their perceptions of the political direction of the future.

At that time, it appeared that the new administration might simply cease any pressure on the sides to reach a two-state solution. This was bound to put most settlers at ease.

It is common to speculate that many West Bank residents are pragmatic, “economic” settlers who moved to the occupied territories for the government benefits and cheap real estate, but who are not truly opposed to a two-state solution. But the December survey, which had an oversample of 300 settlers for greater statistical significance, showed that a wide majority of 77 percent oppose a two-state solution on principle. Nearly half of the settler sample says they are “strongly” opposed. Just 17 percent support the broad notion (the remaining 6 percent declined to give an opinion). Only a few percentage points “strongly” supported two states.

This opposition isn’t just theoretical. The survey also tested individual items of a “traditional” two-state solution. The item regarding settlements read:

“The Palestinian state will be established in the entirety of West Bank and the Gaza Strip, except for several blocs of settlements, which will be annexed to Israel in a territorial exchange. Israel will evacuate all other settlements.”

Fully 80 percent of the settlers opposed this, and 17 percent supported it, similar to the 17 percent who supported the two-state solution overall. In other words, a very large majority of the settlers oppose an item that is basically the keystone condition for a two-state solution.

It is an ominous result for those who argue that a two-state solution is still viable, either because most settlers will not have to move, or that only a small portion are ideologically opposed to dismantling settlements.

By some estimates, about 80 percent of settlers live in the blocs, which means that most of the settlers interviewed here come from blocs. This implies that serious opposition to evacuation comes within the settlement blocs as well; it isn’t just about the self-interest of the minority who would have to move.

Further, after hearing all the terms of the two-state solution, respondents were more resistant. When asked if they would support the full package, 82 percent now opposed the deal compared to 77 percent who opposed it in principle prior to hearing the details. Most of those moved from the “don’t know” response.

In this survey those who were opposed to the full agreement were offered a series of incentives designed to shift their attitudes. One incentive specifically addressed settlers: “Settlers are allowed to choose to stay in their homes after the Israeli withdrawal, to keep their Israeli citizenship and at the same time have their safety guaranteed by the Palestinian state.” But fully 91 percent of the settler respondents said they would continue to oppose an agreement that included this item.

With such a categorical “no” to compromises and the two-state concept, one must ask: what do the settlers in this survey envision? Just over one-quarter support one equal state for Palestinians and Israelis, a figure notably higher than among Jews inside the Green Line (18 percent) and lower than support among Palestinians (36 percent).

In the months leading up to this survey, another option that has been increasingly prominent is annexation of the West Bank to Israel through potential legislation and by the legalization of settlements by law. The survey tested an option reflecting the scenario of annexation without granting equal rights to Palestinians. Among Israeli Jews inside the Green Line, nearly 30 percent supported this (not a small portion in itself). Among settlers, nearly half (46 percent) favored it. This is statistically tied with settlers who opposed it — just 0.3 percent fewer.

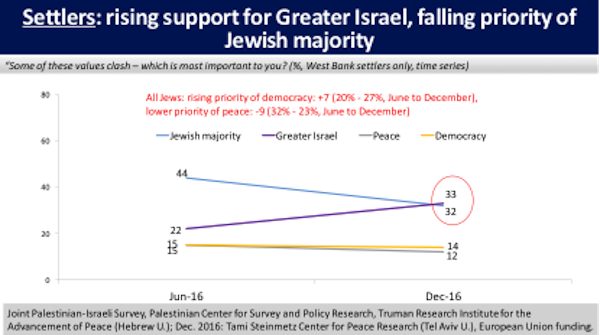

The perception that annexation may be a step closer to reality appears to have propelled one of the biggest changes seen in December, relative to the previous survey in this project, from June 2016. When asked which is the most important value for Israel from a list of four – Jewish majority, Greater Israel, peace, or democracy – a plurality of Israeli Jews chose the Jewish majority both times (just over one third).

In June, even more settlers (44 percent) chose “Jewish majority,” while the second most popular option was “Greater Israel,” at 22 percent. But six months later, this trend was reversed: by December, 32 percent of settlers cited “Jewish majority,” (the condition for ensuring a state that is both Jewish and democratic, by virtue of its majority). This time, most settlers (33 percent) chose “Greater Israel” – an 11-point rise, within the margin of error.

It seems that the small steps taken to legitimize the concept of “Greater Israel” in December made it look that much more real.

Note: The full public release of the survey is available here. The sample sizes were 1,270 Palestinians, and 1,207 Israelis – of which 300 were Jewish residents of the West Bank, and 180 were Arab citizens, weighted to their actual size in the population. Each poll has a margin of error of +/-3 percent.