Like all refugees, Ahmad Badawi Mustafa Ayoub left the world unmoored, his memories rent from the land that made them. But his story, like Palestine’s itself, will matter well beyond the next negotiation. No empire, no flag, or sovereign can change that.

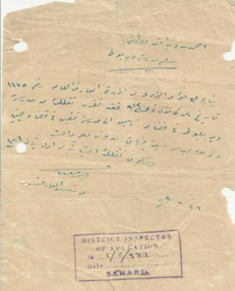

The Government of Palestine’s Directorate of Education, from its Samaria branch in Nablus, informed Ahmad Badawi Mustafa Ayoub that his teaching duties had been re-assigned on December 8, 1936. The 35-year-old had 11 days to report to a new school in Deir el-Ghusoun, a village that, according to a 1931 British census, was home to some 450 households, all of them Muslim.

It was in this boys-only school that the third eldest of my five aunts learned to read and write. While the other village parents kept their young daughters at home, my Palestinian grandfather, the teacher from Samaria, sat his at the classroom’s helm, where the lords of the British Empire held no rein.

In this post-peace era, palls cast over our long negotiation with Israel, these little histories can seem too quaint. After all, with so many threats against our identity, so many of our people stripped of agency, we Palestinians must spar with an awful present. But in this fight, our family chronicles make for more than wistful conversation. They give us more reasons to endure.

I was reminded of this while scrolling through an archive of my grandfather’s papers, struggling to draw some perspective from the rush of eulogies for Oslo’s ninth life. What I discovered — in his Ottoman birth certificate, his British teaching credentials, his various letters from this or that Jordanian directorate — was evidence of a life more resolute than the three sovereigns that defined it.

Ahmad was born in 1901 to Al-Haj Mustafa Ayoub, a Sufi poet from the village of Majdal Sadeq and was a subject of the vast and waning Ottoman Empire, which had by then ruled Palestine for some four hundred years. When his son was barely out of infancy, Ayoub (Arabic for “Job”) moved his family to Shweikeh, just outside the northern Palestinian town of Tulkarem. There, Ahmad completed his early schooling before enrolling in Jerusalem’s Rashidiya School.

According to a biography written by another of his grandsons, the day of Ahmad’s departure was a festive one, with neighbors and their children gathering to see the young pupil off. Back then, it seems, it was a sight to behold: a village boy bound for Jerusalem, where only a select few attended its finest institutions.

Rashidiya counts among its alumni the Palestinian nationalist poet Ibrahim Touqan, whose signature work from the 1936 Arab Revolt, the longest sustained nationalist Palestinian uprising against British Mandatory control, eventually became the lyric to Iraq’s national anthem. Although Ahmad completed his higher-level teaching certificate there, a British administrator ordered him back to the plains of Tulkarem, where he was to open new schools in the then-distant villages of northern Palestine.

And so he did. In nearly four decades of service to the Palestine he knew, my grandfather helped rear two generations of would-be citizens. To this day, some of his pupils from that era, all septuagenarians themselves, will recall how ustaz (teacher) Ahmad used to strike fear in the hearts of this or that peer, dissuading others who might foolishly be inclined to mischief. I knew Sido (grandfather) as terse and forceful, too, but I found these qualities reassuring, like the relentless rhythms of a tightly formed qasidah (poem).

In a devastating elegy to his “suffocated generation,” the Damascene poet Nizar Qabbani counsels the children of the Arab nation: “You don’t win a war with a reed and a flute.” But my grandfather, like so many of his comrades from the time, fought a different kind of war. He outlived Britain’s reign and the Ottomans’ before it, and when he retired, his end-of-service certificate, dated June 19, 1961, came stamped by the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan’s Directorate of Education. In Nablus.

The last time I saw Sido, he was sitting on the edge of a bed in the basement of my aunt’s home in Amman. The day marked nothing in particular — no anniversary, no celebration, no birth or death. Yet there he was, ever the school teacher, his kuffiyeh draped over a black suit jacket, now loose over an atrophied frame.

“May I enter, Sido?” I asked in my timid Arabic. He acknowledged my presence, without saying a word, and I walked in to sit beside him. There, seven decades between us, we sat shoulder to shoulder and let the silence have its say.

He would die soon after, at the age of 92, just as Bill Clinton’s “peace” ushered in a new era of displacement and loss.

Like all refugees, Ahmad Badawi Mustafa Ayoub left the world unmoored, his memories rent from the land that made them. But his story, like Palestine’s itself, will matter well beyond the next negotiation.

No empire, no flag, or sovereign can change that.