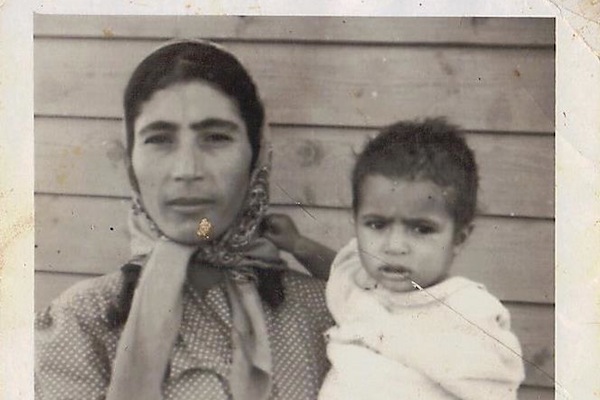

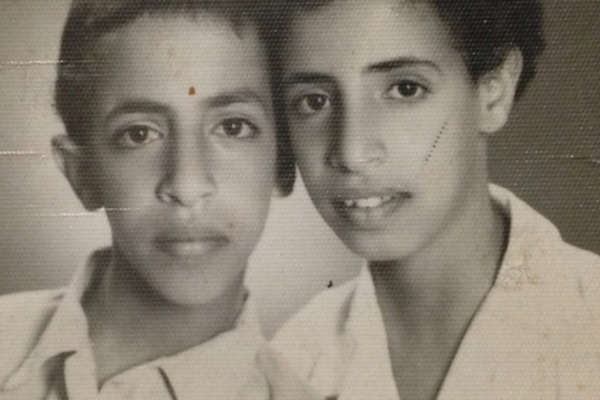

In the years following Israel’s establishment, thousands of Yemenite babies, children of new immigrants, were reportedly taken from their parents by the medical establishment and disappeared. Now two filmmakers are working to bring to light the stories of the families who were torn apart.

By Tammy Riklis and Yonit Naaman

The past half year saw the release of acclaimed Hebrew web series “Neviim: Operation Amram,” which takes a closer look at the Yemenite Children’s Affair and the families whose children disappeared in the early years of the state. The 12-part series, which was released piecemeal over the past year, follows the activists from the Israeli non-profit organization, Amram, as they went from town to town to collect painful testimonies from families whose children disappeared.

Each episode of the series shines a light on a different stage of this long journey, which begins with a meeting of Amram activists on the balcony of Naama Katiee in Haifa. The group ponders the problem of explaining to children that other children had been kidnapped in this country (“How can I tell her that doctors kidnapped children? She will refuse to go to the doctor.”) and moves on to the stories of people, families, and entire communities that went through hell. This is a past that some are living every day, a past that had been silenced and repressed for decades.

What gives the series its strength is the camera’s unwavering focus on the conversations between the activists and those who give their testimony, without any background noise or commentary, creating a strong feeling of intimacy. The men and women telling their stories are Israelis from age groups and ethnicities not commonly seen on the screen. In fact, for years their story was not part of Israelis’ collective memory, which is full of trauma and bereavement. Now, for the first time, it is being documented as a unique piece of history that affords a peek into the life of new immigrants from Arab countries in the 1950s. Speaking about a kidnapped child or sister without apology or cross-examination is made possible by members of the third generation who “become the mouthpiece of the first generation. “It’s a heavy responsibility but it has to be done” says singer Neta Elyakam in the sixth episode, which looks at the kidnapping of Moroccan children in the southern city of Netivot.

Amram’s became the focus of much attention last year after establishing an online archive of testimonies, DNA tests, and a call to open state archives and files on adoption (this struggle resulted in opening up some of the archives, which included deliberations by the various state commissions of inquiry that looked into the affair). Haokets has for years publishing for years materials about this affair, its twists and turns. The fact that the topic refuses to vanish from the public agenda is encouraging. The series is part of the effort to broaden the scope of the discussion, to enlist other groups in the struggle, to raise the consciousness, and to locate other affected persons from communities which in the public mind had not been previously connected to the affair.

For example, Operation Amram’s tenth episode looks at kidnappings of children from the Iraqi community, was posted in a Facebook group titled “Preserving the Iraqi language,” and led to a deluge of responses, such as: “The episodes cause more and more testimonies to come to the surface, they create patterns of thinking, people watch them and realize that they are part of something bigger.”

We met with Elad Ben Elul and his partner and co-creator, Yossi Brauman, to find out how they cope with dealing with this raw wound so intensely.

Heroines of the Mizrahi struggle

Ben-Elul (30) and Brauman (34) have been a couple for eight years. They live in Tel Aviv, and over the last two years they have been working together in their spare time on several viral web series whose intent is to influence the social agenda and promote change.

“We have discovered the vast advantages of such a series that render the pursuit of TV superfluous”, says Yossi, who filmed and directed the series, and who admits that for the last six months he has been filming and crying, crying and filming. “You can see how the camera is trembling. Elad cries while editing. This is powerful stuff.”

Before Operation Amram, Ben Elul and Brauman created the highly-discussed web series “Prophets,” made up of 10 episodes dedicated to the new heroes and heroines of the Mizrahi struggle. When filming the episode with activist Naama Katiee, in which she spoke about the Yemenite kidnappings, the two realized that this topic required far more coverage. “The episode with Naama went really viral” says Ben Elul. “It was clear to me that this story deserves its respect. In general, the male “prophets” did not attract as wide an audience as the women. I am glad that the women’s leadership in the Mizrahi struggle was duly presented and documented.”

Brauman: On June 21st of last year, the anniversary of Rabbi Uzi Meshulam’s death (Meshulam and his followers attempted to force the state to come clean about the kidnappings of Yemenite children by barricading themselves in his home, where they stockpiled with weapons), is dedicated to the awareness of the kidnappings of Yemenite, Mizrahi, and Balkan children, Amram launched a website with a database of testimonies.

At this stage, Elad and I were thinking of creating a different series that would focus on other “prophets.” I checked their website and saw that the database was organized according to the year of abduction, hospital, and country of origin. There were hundreds of testimonies, each recorded on video. It was like stumbling upon a Spielberg archive. It felt like a movie rolling before my eyes and I realized that this was what we had to do.

I asked Elad and he said that it should be another series and not a movie. A series that takes place here and now. We shoot, edit and upload.

You knew that it was going to be a web series?

Brauman: Yes. Aside from the fact that we are able to reach a wider audience, a web series is a direct way to speak with the viewers, to hear them, to see Facebook shares and reactions. Television series have other obligations, they depend on budget, censorship, time, and bureaucracy. Here we decide everything ourselves.

Ben Elul: “This is an excellent way to bypass the institutional route, in activism and in the media.”

Brauman: “Most media content is directed towards a particular audience speaking a particular language. Our audience includes people from across the political spectrum, including people from the radical left, proponents of BDS, and people to the right of Naftali Bennett. Our audience disregards dichotomies.”

What was the starting point of the series?

Ben Elul: “We started with the understanding that the voices of the testifiers, the families, are the most interesting and the most important aspect of this story. We wanted the series to be in the present, not a retrospective. We wanted to shoot, edit, compose music in real time. In this way the series became not only a documentary about the struggle, but also a tool in the struggle.

Brauman was born in Petah Tikva, studied film at Camera Obscura, directed independent films, and had his work screened in Berlin and at the Tel Aviv Pride festival. He previously worked as a journalist at Time Out Tel Aviv, and today makes a living by managing media and content. We asked him if there is anything in his biography that connects him to this painful affair. “I am half Polish and half Romanian. My father was in Sobibor, he escaped on his own. There are Ashkenazim around me who feel hurt that I am taking on this project. They ask me ‘Why are you doing this, have you forgotten where you came from?'”

Ben Elul: “The Holocaust of European Jewry is beyond comprehension, and what your family went through is crazy. You are a remnant. According to international law, kidnapping of children is also considered genocide, since it amounts to the dilution of a population. It is impossible to know how many Yemenite Jews could have been here today. Thus it seems to me that Ashkenazi Jews can identify with the plight of the Yemenites.”

Ben Elul was born in Jerusalem and is a doctoral student in anthropology at Tel Aviv University. “Most of my adult life is connected with anthropology, academic or applied”, he says. “It is important for me to speak outside of the academia, to speak with people.”

Between activism and documentation

What can you tell us about your presence in the families’ homes?

Ben Elul: “First of all, we tried to be as sensitive as possible. We told them at every opportunity: ‘We’ll do whatever you want. We won’t shoot if you don’t want us to, if you do not like the angle we’ll shoot from another point. If you’d rather have different lighting, we’ll change it, no problem. Nothing is a must.” We are dealing with people who are describing events that the world cannot yet digest. They are building the story for the world.”

Brauman: “The families were often very delicate. They spoke in sentences that were sometimes difficult to fathom, but each sentence spoke volumes. It’s an abyss. Sometimes, while filming, we experienced things at a certain level of intensity, and then later, while editing and arranging, we would experience them at a different level. A volunteer who transcribed one of the chapters said that during the transcription process he understood the severity of what was being said. The activities of documenting, of providing access, are very powerful.”

Ben Elul: “We treated it with utmost respect. These families let you into their homes with cameras, and the moments we capture are very painful. It has a healing potential, but clearly the difficulties and the loss they feel are ever present. This was an emotional challenge, for us as well as for the people of Amram.”

Brauman: “We were in Petah Tikvah filming an Iraqi family where the father spoke about the abduction of his firstborn son. I lost my father when I was two-and-a-half years old. This man is surrounded by women and I, too, have only sisters. This father talking about his son, that was really shattering. When we left, I said to myself that I had to go right away to my father’s grave to light a candle. I really collapsed in the street that day. I cried non-stop.”

Ben Elul: “There were many testimonies that made me cry, but the most moving one for me was the segment where Naama meets members of the Bnei Akiva youth movement. These were mostly Ashkenazi youth in a traditional Jewish youth movement, and Naama created a connection such that this story can be viewed as a Jewish story.

The families, too, always see the element of Judaism and spirituality. These are religious people who experienced something and they interpret it from a religious point of view. As the series progressed we understood these connections ourselves. We decided not to work on the series

on Saturdays in order to honor the families. Instead we honored the Sabbath.

Oppression olympics

One of the interesting decisions Bauman and Ben Elul made was putting the victims and the perpetrators — the establishment — on opposite sides. The two say they have been told many times that there is a missing side to the story – that of the kidnappers, the doctors, the nurses. “Our answer is simply that we do not have these testimonies”, says Ben Elul. Brauman adds that the series wants the audience to stop talking about individuals and focus on state bodies and organizations that took part in the kidnappings. “Speak about organizations. No one has to be hanged in the town square. Organizations like WIZO and Hadassah, the state and its archives owe us the answers, not this nurse or another.”

Bauman and Ben Elul speak about the mayhem that erupted during the screening of the series in Tel Aviv when Amram activist Shlomi Hatuka spoke about the role of Ashkenazim. “I know the woman who made the most noise,” says Brauman. “She stood in front of the panel and said ‘It is not nice of you to speak like that about the Ashkenazi Jews, their children were kidnapped as well.’ After the event people asked me ‘You were there, the only Ashkenazi on the stage, why didn’t you say anything?’ I understand that this is difficult for them but I also know full well that in this case we have to take a step back. Ashkenazim are used to being in the spotlight. We do not have to be in the spotlight in this case. We are not the victims here, we are not the ones who were harmed, even if we do not like hearing that the perpetrators were Ashkenazi Jews.”

Ben Elul: “Amit Hai Cohen, who composed the series’ soundtrack, said at the screening that each one of us is a victim of kidnapping. It’s a spectrum. There is the classic tale of the Yemenite woman whose baby was kidnapped, but there are many manifestations of kidnapping. In a sense, someone who is separated from his family and sent to a boarding school in Netivot is a child who has been abducted by the establishment. This affair is in essence the DNA of everything. What is now going on in the Israeli discourse is like extracting a tooth. We are afraid to acknowledge the pain of others, because if we do, it will be doomsday.”

Brauman: “The Ashkenazim have to understand that you suffered the way I suffer. We are both victims. This is the switch that the Ashkenazis have to make, and I say this as an Ashkenazi. If I have one complaint against the Ashkenazim today, it is not that they kidnapped, but why they take part in silencing and denying the kidnappings. Luckily, on our page we do not have responses from kidnapping deniers, but we know of one case of a woman who shared a segment and the deniers were all over her.”

What kind of denial did you encounter?

Ben Elul: “All the standard ones; that the kids were sick and died; that they were better off adopted than living in the conditions they lived in; how is it that not one adopted child has been found; and, of course, the theory that the young state was a ‘mess,’ in which these things could have easily happened unintentionally.”

Brauman: “The families are not seeking civil war, they do not want to turn the state upside down, they do not want to put Ashkenazim in jail. The deniers behave as if it had happened to them. It’s unbelievable, the hue and cry: how dare you mention the Shoah? How dare you say this or that?”

How was the series received by the state and the mainstream media?

Ben Elul: “It’s interesting. It is impossible not to see the enormous influence of the series on the discourse, it is hard to disregard its relevance, the fact that it is widely talked about, but they do not write about us, do not interview us, and do not mention us.”

Brauman: “We went with Naama to Ynet’s studios. They did a report about the experiments, but then decided to shelve it. It is not clear why. The media knows that it is a hot topic.”

A version of article was first published in Hebrew on Haokets. Read it here.