On the backdrop of rising discrimination and violence against Israel’s Arab citizens, a new children’s book invokes the spirit of friendship between Arabs and Jews, giving us at least one thing to look forward to in 2016.

By Yoni Mendel (Translated from Hebrew by Ami Asher)

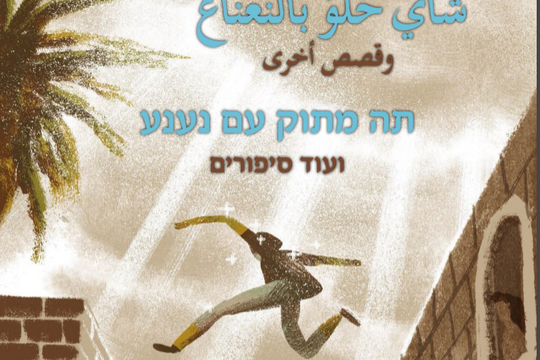

A new children’s book, “Sweet Tea with Mint And Other Stories” is being released in a climate of increasing discrimination. With the Education Ministry excluding books from its curriculum out of fear of “miscegenation,” at a time of record low of Arabic proficiency among Jews, and with the images of Jews dancing and stabbing photos of Palestinian babies still fresh in mind — this book is perhaps the only good reason to look forward to 2016.

Until this very moment, I have been struggling to understand why reading the book brought a tear to my eye. Was it because of one of the passages in the book? Because of the simple human gesture it describes? Or perhaps because of the Israeli reality into which it has been released? Either way, the birth of this book is nothing short of a miracle.

The reality in Israel of 2016 is a sea of hatred between Jews and Arabs, with attempts by demagogic politicians, researchers and “interpreters on Arab affairs” to prove that we are in the midst of a so-called “clash of civilizations” with Islam. It is a country that, since its very beginnings, has consistently sought to ignore the Arab-Jewish culture. A country run by a man who, just last March, encouraged Jews to vote in the elections because “Arab voters are heading to the polls in droves.” This is the dark reality in which a collection of stories and legends written and translated by Jews and Palestinians proud and courageous, a collection of stories and legends written and translated by both Jews and Palestinians is being published. Every story is published in Hebrew and Arabic.

What will Bennett say?

Sweet Tea with Mint And Other Stories is a collection of stories that invokes the Jewish-Islamic bond, and more generally the legacy and friendships between Arabs and Jews. It also includes the values shared by followers of Islam, Christianity and Judaism; the social responsibility we have for all inhabitants living in the same country; the value of equality regardless of ethnicity and religious affiliation; the moral requirement and the obligation to protect and fight for the weak — those without status, language or a state. No less important, it evokes the power of religious faith, not as a blueprint for nationalism, but as a force of tolerance towards all humankind, and the role of Jewish, Muslim and Christian traditions not in promoting hatred and separation, but as a moderating and reconciliatory force.

Education Minister Naftali Bennett will probably have to scratch his head a few times when perusing this book, if indeed it does make headlines. On the one hand it is a collection of stories in which the religious-traditional discourse so valued by Bennett is a leitmotif. Jewish religious references are central to it — including the revelation of Elijah and the origins of King David— stories related to the Jewish holidays and key religious values, be they prayer and giving charity in secret, or stories relating to the synagogue.

This may sound familiar enough to Bennett, but alas, the Jewish religion is mentioned in the book alongside Islam and Christianity, and verses from the Old Testament appear next to verses and stories from the New Testament and the Quran. Moreover, Judaism is referred to in the book mostly in the context of Jews of Mizrahi origin, for whom Arabic and Arab culture are not the enemy. Furthermore, the daily lives described in the book are those of Muslims, Christians and Jews living together in this country, as well as in other Middle Eastern countries, as true neighbors. Furthermore, the names of many of the book’s protagonists are both Jewish and Muslim – Na’im, Aziza, Sisou and Mimoun.

In the same vein, the underlying message of the Jewish holidays it talks about is neither “we will forever live by the sword,” as was recently promised by Prime Minister Netanyahu, nor that “in every generations the gentiles rise up against us.” Instead the book imbues us with a sense that equality is possible, and that the weak must be protected and fought for, and certainly not driven out of the country as so-called “infiltrators.” The moral of the stories is that mutual and community responsibility and solidarity cuts across religious and ethnic affiliations, and that joint struggle is one proven way of keeping evil at bay.

An alternative to nationalism

It appears there is a chasm between the book’s educational messages and the messages that Israeli decision makers — not to mention a great majority of local public officials, whether secular, traditionalist or national-religious — have been promulgating. Thus the book offers a sound and humane alternative — a traditionalist-Arab and traditionalist-Jewish alternative for the one-dimensional segregationist discourse that had become the default among Jewish Israeli society. Moreover, it forces us to think. It is not informed by an us-against-them or good-versus-evil mentality, but requires the reader to see the human in human beings.

The book includes six stories. Three – by Hadil Nashif, Altayeb Ghanaim and Sheikha Hussein Hlewa – were written originally in Arabic, and three were written originally in Hebrew by Ronit Chacham. Every story is presented first in its original language, followed by its translation into Hebrew or Arabic, respectively (the translators from Arabic are Yehouda Shenhav-Shaharabani and Altayeb Ghanaim; the translators from Hebrew are Hussein Alghol and Altayeb Ghanaim).

The book’s characters and stories, interestingly, are situated in the socioeconomic and political margins, yet the reader quickly reveals that their first and most important struggle is not for money or prestige, but primarily for recognition, equality and justice. Accordingly, the stories unfold mainly far from the Israeli socio-geographic center — in the Tiberias market, in the Arab border town of Baqa al-Gharbiyye, in desert dunes, in Haifa’s Wadi Nisnas neighborhood, in the Jewish border town of Sderot, in Lod-Lydda, and even in a Jewish quarter in a Moroccan city. Its characters call upon us to look within ourselves and straight into the eyes of Israeli society and feel, above all, embarrassed. Embarrassed, first and foremost, for the painful lack of Israeli children’s book that take its readers through the alleyways of Wadi Nisnas and Sderot. Secondly, we are embarrassed by the lessons we learn from our society. This collection is mostly about characters who dare to be kind — in both thought and action — without any reward. They are willing to go out of their way because they see the Other.

The stories are about the transformation of individuals and society at large when they manage to see the Others and understand their plight. It is a book about courage, about the ability to make a difference. It is a book about poverty and richness and the boundaries between them. It is a book about social justice, but one that sets clear priorities in advance: not Tel Aviv’s middle class figures who profited from the 2011 social protest, such as Yair Lapid. It is about Arabs and Jews, mostly religious or traditional — including Jewish immigrants from the former Soviet Union and Arab countries — that have almost always been marginalized and rarely appear in children’s stories.

It is a courageous book, no less. Its power lies mainly in the ability to juxtapose members of different religions and write about them sincerely. There are not too many children’s books written in both Arabic and Hebrew, let alone books that bring together the wealthy Mimoun and the poor Sisou family in Morocco for a Passover seder, where the former finds out that even he can be their Elijah. Or take Maha in Wadi Nisnas who buys a raincoat for old Abu-‘Issa and explains to her son Fadi that she did it not so that the old man would give his coat to Jesus (Issa), but out of the hope that the old man’s “happiness would touch his heart.” The book’s ability to tell stories and legends centered on Jews, Muslims and Christians, in order to reveal the the human spirit in every person, in every society, in every religion — is so rare in these parts.

A response to Yinon Magal

In late November 2015, Yinon Magal, then a member of Knesset in the Jewish Home party — which controls the Education Ministry — gave his last speech in the Knesset. This was a few days before several women complained that he had sexually harassed them, eventually leading to his resignation. While reading Sweet Tea with Mint And Other Stories, I recalled this long forgotten speech, a well-planned, demagogic trick that Magal chose to deliver in lousy Arabic. Using “right-wing-Zionist-Arabic,” full of hatred for Arabic speakers, Magal hoped to “tell you (Arabs) the truth.” But truth was nowhere to be found, and instead Magal resorted to much of the cheap incitement we are so used to hearing from the Israeli political right and center. “You do not kill us because of the occupation or the settlements,” Magal said in his Arabic as he stared down the Arab MKs, “the truth is you kill and hate us because we are the landlords.”

He then proceeded to declare that “a Palestinian state will never be established,” and referred to Surah 7, verse 106 in the Quran, which supposedly proves that “this is our homeland.” The Arabic language stands in defiance to Magal, along with the message of the Sweet Tea with Mint And Other Stories, which is written in real Arabic and includes references to the holy scriptures of all three monotheistic religions. But unlike Magal, who represents the bankruptcy of Israeli society in more ways than one, this book charts the course our society could have taken.

Despite all its treasures, however, the book might cause its readers to feel helpless. Israeli schoolchildren would obviously benefit from it enormously. Surely if they read the letter written by Matilde to Maha and Fadi, or they smell the stones as they are heated up in Rouhama Sisou’s courtyard, or if they listen to Shlomi who fights against the expulsion of African refugees because “that’s the humane thing to do,” something will touch their hearts. They will be empowered to dare and see the Arab as they see the Jew, to protest against the expulsion of refugee children, to no longer consider Islam their enemy. But the helplessness lies in the feeling that while our children may be willing to listen, the Israeli adult world – from the Education Ministry to the great majority of school principals and teachers, and even parents – will not be willing to tell those stories to their children.

“Sweet Tea with Mint And Other Stories” is a collaboration of the Department of Education at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev and Hagar: Jewish-Arab Education for Equality, produced with support from the European Union. There will be a book launch on January 12, 2016, at 5:30 p.m., at the Ben-Gurion university. The public is invited.

Yoni Mendel is the projects manager of the Mediterranean Unit at the Van Leer Jerusalem Institute, and co-editor of the book review section of the Journal of Levantine Studies (JLS). This article was first published in Hebrew on Local Call, where he is a blogger. Read it here.