Between unequal distribution of municipal taxes that discriminate against development towns and admittance committees that bar entry to those who do not belong to the ‘white tribe,’ the Left must lead the struggle against the kibbutz’s sectorial policies.

By Elad Wolf

Since the founding of the state, the kibbutzim have undergone a process of privatization. From their socialist infrastructure, the kibbutzim and the moshavim have turned into the enemies of equality and solidarity. Perhaps the time has come for the Left to move forward and release its hold on the kibbutzim.

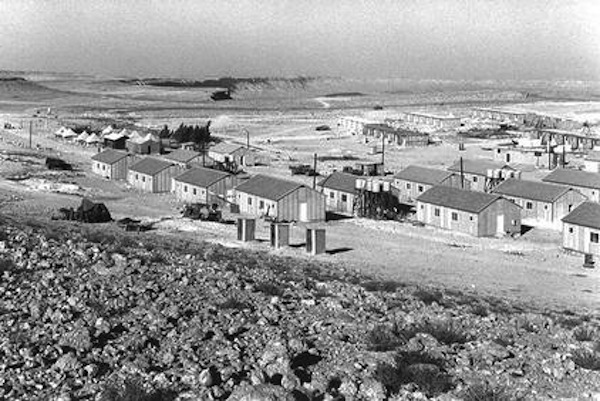

The biggest question one must ask is what will happen when the residents of Israel’s impoverished development towns decide to engage in a struggle. A real struggle that will include banging on the kibbutz gates and blocking its access roads. When they decide to rise up against the historical injustice, according to which municipal taxes go solely to the tiny kibbutzim and moshavim at the expense of dilapidated development towns, or simply rise up against the admittance committees that refuse to accept them. Perhaps they could also demand that the kibbutzim divvy up their land for the purpose of building public housing.

Where will the Left be on that day? Will it shut up? Will it protect the kibbutzim? Will it call for negotiations? Or perhaps it will decide to take the side of the development towns? Choosing any of these options aside from the last one is an affront to the very idea of the Left. But if you ask any of the self-defined Israeli leftists this very question, they aren’t likely to choose the last option.

The development towns must engage in this struggle. The distribution of municipal taxes and the national budget is simply unfair. There is a preference for the rich, white Israelis over the hungry workers — it is as simple as that. Take, for instance, the debt accrued by the development town of Yeruham as opposed to the unreasonable growth of the Ramat HaNegev Regional Council’s (which presides over mostly kibbutzim and moshavim) budget. While Yeruham is struggling to rise above its debt — without any resources of its own — the state keeps transferring huge sums of money in municipal taxes to the adjacent Sha’ar HaNegev Regional Council; this despite the fact that all the IDF bases are in or around Yeruham.

Or take the factories, hotels, and tourist services at the Dead Sea, which constitutes a huge source of income for the state. All of the municipal taxes go directly to the coffers of Tamar Regional Council. Take an even closer look and you’ll find that the majority of the workers at the Dead Sea hotels are contract workers from development towns such as Arad or Dimona.

But it doesn’t end here. Those who do not belong to the same “white group” will also never be able to penetrate the borders of the kibbutz. The admittance committees are still in effect, meaning that Arabs and Ethiopians will never be able to become kibbutz members, while Mizrahim only rarely make it. The Israeli Left must not only take the side of the development towns, it must lead this struggle in the Knesset and in the streets.

During this past election I learned two important things: the first happened while I was managed the campaign for a candidate for Meretz’s internal elections. While making phone calls to voters from the kibbutzim, we heard time and time again that they vote “according to the kibbutz’s dictate,” or according to “what is good for the kibbutz.” My kibbutznik friends told me that I will never be able to truly understand, but that they are beholden to the kibbutz. The candidate who ran on behalf of the “kibbutz” is someone who most people didn’t even like, who in the past opposed raising the minimum wage, and who demanded lowering taxes on contractors who bring in work from outside Israel. But the dictate stood.

The second thing I learned happened while traveling between small campaign events across the country, some of which took place on kibbutzim. The question we kept hearing was: “What are you planning on doing for us?” The Left’s response must be: Why must we do something special for you that isn’t being done for your neighbors? Why are you better?

But the Left does not say these things.

Instead the Left continues to safeguard Knesset seats for members of the kibbutz and moshav movements, in order to vote in a way that does not reflect the worldview of the Left, but rather to serve the needs of the kibbutz. After he was kicked out of the Knesset, Meretz’s kibbutz representative, Abu Vilan, said that it is inconceivable that the Left would just toss aside a representative of the movement, and that the kibbutzim should consider supporting a party that will look after their interests.

The struggle between the heads of the powerful authorities against the weak ones proves this point. On one side we see several members of the Labor Party who are interested in redistributing the budget and challenging this unequal power dynamic. On the other side we see kibbutz and moshav representatives from the Labor Party who stand alongside the heads of powerful councils. The latter are using their political power to shut down any attempt at redistribution.

If the kibbutz movement is interested in being a sectorial party, let them do it. The door is wide open. But if they believe in the interests of all people, they must choose between Right and Left, between the principle of equality and dog eat dog. And no, solidarity is not solely reserved for kibbutzim; solidarity should also be reserved for their Arab, Ethiopian, and Mizrahi neighbors.

Elad Wolf is a Meretz activist.