A group of dedicated activists have been working tirelessly over the past several years to force the state to come clean about the disappearance of hundreds of Yemenite children in the early days of the state. They might just succeed.

One of the aspects that is easiest to forget about the Yemenite children affair is that it is not a historical one. The disappearance of hundreds of Yemenite babies is not an old story, but rather a continuing injustice — even today. For the families who lost their children, who still do not know their fate, it has been a festering wound for nearly 60 years.

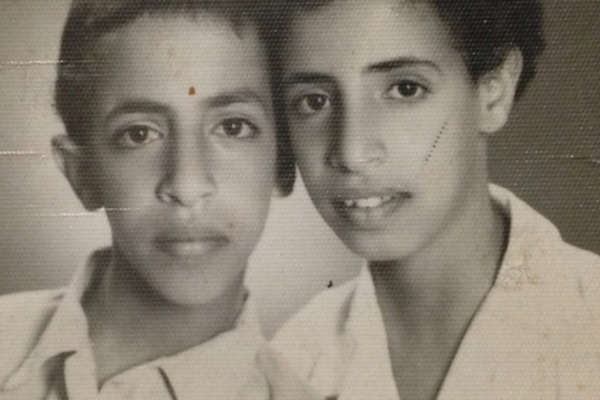

This means living an entire life of pain and doubt, of knowing that you wake up in the morning and drive to work, go to the supermarket, pay taxes, while your country remains silent over the disappearance of your child or your sister. That the doctors who treat you were educated by those who took part in disappearing children. That politicians deliberately prevent the state from formally recognizing the injustice, from apologizing, from compensating the family, and from supporting the attempt to find the children. That one of your close family members, whom you have never met, could pass you by on the street without knowing they have another family.

It is an unbearable burden to have to carry for 60 years. To understand the pain, all one needs to do is listen to just a few of the hundreds of testimonies published by Amram, an Israeli NGO dedicated to researching and exposing the disappearance of the Yemenite children. Through the tears of the parents, sisters, and brothers, one can understand how every day without answers is another day that the children are kidnapped — all over again.

Over the past few years, a small group of dedicated activists from Amram and other organizations have been able to break through the silence. They do not organize in a vacuum — it was the decades-long struggle by the families that led them to the journey toward recognition. Exposés published in newspapers such as HaOlam HaZeh in the 1960s and Haaretz in the 90s also broke that silence. The heroic struggle of Rabbi Uzi Meshulam, who led a campaign to try and force the state to come clean about the affair, further raised public consciousness.

Over the years, however, the establishment repeatedly denied the allegations. Commissions of inquiry worked to bury the issue, while many of the testimonies remained classified for dozens of years.

In the years since it was founded, Amram has done incredible work: through recording and publishing testimonies, holding discussions and conferences to raise public awareness, they have been able to significantly influence public opinion on the Yemenite children affair, to reach new audiences and successfully force the state to release a trove of previously-classified documents.

These activists succeeded in putting together a broad political coalition, including feminist and Mizrahi organizations, the Activestills photojournalist collective, Physicians for Human Rights-Israel, Ethiopian-Israeli activists, and members of Knesset from both Meretz and the Joint List.

On Wednesday of this week, Amram will hold a demonstration in Jerusalem, which will focus on three demands: first, that the state formally recognize that kidnappings indeed took place, apologize to the families and the children, and hold an annual day of recognition to mark the affair. Secondly, the activists demand that the state invest the necessary resources to unite the families who were torn apart. Amram has already succeeded — through D.N.A. tests, perusing adoption files, and public activism — to unite two families with children who were kidnapped and given up for adoption. There is no doubt that the state, with all its resources, will be able to do more. And lastly, Amram demands the state retroactively acquit Rabbi Uzi Meshulam, who was sentenced to six years after being convicted of violent offenses as part of his struggle to raise awareness over the affair.

These are modest demands. Like my colleague Noam Sheizaf, who researched the topic and made a film about Meshulam’s struggle, I also believe that recognition and reunification are not enough. The state owes these families real compensation. It won’t bring back the children, nor will it undo the injustice, but it will be the way to show that the state not only talks about responsibly and regret — it actually does something about it.

Just last week, the government rejected a bill by opposition leader Isaac Herzog (Zionist Union) — along with 37 MKs from Likud, Meretz, Shas, and the Joint List — to hold an annual memorial day for the sake of “solidarity and humaneness,” and to stand alongside the families. The government, it seems, isn’t willing to allow even that.