The Israeli government’s attempts, via the nation-state bill, to erase the Arabic language from this country not only threatens Palestinians, it also undermines Mizrahi identity. But their attempt is doomed to fail.

By Netta Amar-Shiff

When my grandmother, Sa’ida, came to Israel, she worked at Kfar Hadasim Youth Village as a house mother, and needed to undergo a quick process of Hebraization so as to communicate with hundreds of new immigrant children. Although they had much in common, there remained a gulf between them, the most prominent of which was their mother tongues. Hebrew served as a bridge for both the children and my grandmother to a new society in Israel. Her mother tongue was relegated to the personal, and especially the synagogue.

By the time I came into this world, my grandmother had an impressive command of Hebrew, as opposed to her friends who were not forced to work with children and teenagers. And yet she regularly peppered her words of wisdom with Yemeni Arabic idioms. As a fly on the wall during her Shabbat conversations with her friends, I would understand few words — yet the meaning was clear. Only sometimes did my grandmother stop to translate for me. This is how Arabic, my grandmother’s language, the language my mother knows perfectly yet never spoke to me, found its way into my heart.

As a child of Generation X in 1970s Israel, I was part of part of the lost generation of the Israel of the ’80s and ’90s. A generation that includes women and men who today sit in the government. And yet, the melting pot did not totally work on me and many others of my generation. On the contrary, we felt a need to look back at our parents and grandparents’ lost generation. To pave a new path for building a future.

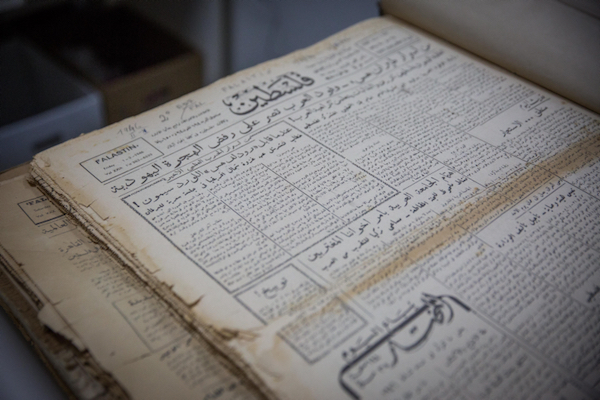

Preserving Arabic as a living language

Our Arab lineages and family histories only became more prominent during the Oslo Accords in the ’90s. The rise of the Mizrahi Democratic Rainbow Coalition and an alternative cultural-historical discourse, in which the “other” Israel demanded a slice of the pie, brought the history of Arab Jews to the public’s attention. This was followed by a flurry of cultural activity, including the founding of the Israel Andalusian Orchestra, new literature, classical and popular poetry, dance, and theater, which looked to Jewish-Arab origins. The enemy within — our denied Arab identity — was now beloved.

This generation’s push to revive the Arabic language — both spoken and written — can be found in various initiatives, such as those by Neve Shalom-Wahat al-Salam and Hand in Hand. Starting mostly in the 1990s, bilingual schools, such as the one my children attend, began popping up across the country. Their goal is to allow Jewish and Arab students to learn and live in both languages — and to view them as equals. A new generation of Jewish and Arab children viewed Arabic not only as a “second language,” but as part of their shared experience.

My efforts to make a change with my children, who read Torah in Yemeni with an Arabic accent and understand my Arabic-speaking aunt better than I do, was given a rude awakening when the Ministerial Committee for Legislation’s decided to approve the so-called nation-state bill, which would strip Arabic of its status as an official language of the state.

The denial of Arabic’s official status reminds me of an Arabic saying: “Denial is the donkey of the law.” The initiators and supporters of the bill are fed by primeval fears of the Arabic language, which they view as a demand on behalf of the country’s Arab citizens for its rightful place in Israel’s law books. Young and old, Knesset members and government officials continue to sanctify the cursed policies of the state’s founding fathers, praising the erasure of what remains of Arabic in this country. They are thirsty to return to the glory days of a pure, white European country that never was and never will be in the Middle East.

As opposed to the despicable human engineering committed by the state leadership vis-à-vis its Arabic speaking population in the first years of the state, we are now living in an age in which the ties between society and the regime are far more complex and multi-dimensional. The borders of language are no longer established through legislation, thus there is no way to force these kinds of processes on the population. The nation-state bill is doomed to fail in the face of this irreversible process by the generation that knows its parents and grandparents, and does not focus on the narrow limits of its religious, ethnic, and linguistic origins.

All of the deep historical currents of this country’s inhabitants stand against this process. Therefore it is incumbent to strengthen the new current, which seeks to educate the present and future generation to learn Arabic as a living language. Not as a language used by the IDF intelligence corps, but as a language of shared living in this country. Everyone is welcome to join.

Netta Amar-Shiff is a human rights attorney. This article was originally published in Hebrew on Local Call.