A few weeks ago, a representative from the office of Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas called Idit Shemer, an Israeli author, in Jerusalem. “We want to print a few copies of “Departing Iraq,” by Mr. Ishaq Bar-Moshe,” said the voice on the phone. “Abu Mazen [Abbas’s nickname] is interested in distributing them at a conference for Arab leaders, which will take place soon in the West Bank.”

Why is the PA’s president interested in a book by a Jewish Israeli writer?

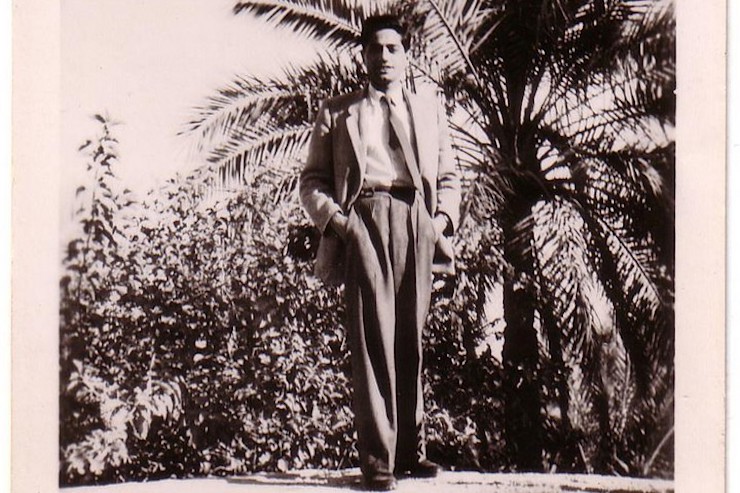

The answer lies in language: Ishaq Bar-Moshe wrote in Arabic. His first important work was published in Israel during the 1970s, and he chose to write it in literary Arabic (Fusha). When he immigrated from Iraq in 1950 at the age of 23, he already spoke Hebrew and wrote fluently in English, but always felt most at home writing in Arabic. Bar-Moshe passed away in 2003.

“How do you think he would have responded to Abu Mazen’s request?” I ask Shemer, his daughter.

“He would have been very happy,” she said. “My father was a man of dialogue and of co-existence. In literary terms, his book is very important. It was his dream to see his book, which he wrote in Arabic while living in Israel, read by Arabs living across the Middle East and the Palestinian Authority.”

The anonymous voice on the phone from Ramallah was Ziad Darwish, a member of the PLO’s Committee for Interaction with Israeli Society. A few days ago, he invited Bar-Moshe’s family to Ramallah.

“President Abbas is very interested in Arab Jewry, and particularly in Iraqi Jewry,” confirmed Darwish. “He wants to distribute Bar-Moshe’s book because it is a first-person account of Iraqi Jewish life. The president believes it is important to raise awareness among Arab leaders of the Jewish communities that lived in their countries,” he adds.

“Arab Jews were an integral part of the Arab world and they held very important positions. Some Jews describe their experience of living in Arab countries as hellish, while some Arabs claim that Jews in Arab lands conspired against the governing regimes in their countries — but the book narrates the reality of the Jews of Iraq during that period. Many people try to deny or hide this reality, which is why the president is interested in distributing his book,” continued Darwish.

This is not the first time Darwish’s committee has recognized authors that most Israelis have never heard of. “Shmuel Moreh met the president,” said Darwish, referring to the Iraqi-born professor of Arabic literature who was a recipient of the Israel Prize. “After his death, we organized a memorial event and invited his family. The president ordered 300 copies of his book ‘Baghdad My Beloved,’ and distributed them to the entire leadership in the West Bank. We cherish Arab Jewry; their influence was profound.”

Bar-Moshe published 10 Arabic-language books in Israel. There were no serious efforts to publish them in any of the Arab states; nor is it clear that Palestinian Arab citizens of Israel were aware of the author. Who was Bar-Moshe writing for, assuming he could not have imagined that one day the Palestinian leadership would be reading his books?

“You had to know my father,” said Shemer. “His truth was important to him. He could not write in another language. When he wrote from the heart, he wrote in his own language, the language of his dreams and his thoughts. He understood that he had a very small readership. He wanted to write and to see his books in print; he would give them for free to anyone who asked, but he also didn’t hesitate to submit book proposals that were rejected. His attitude was: ‘If you don’t want it, no problem. I’ll self-publish and maybe you will see what you missed.””

In a 2003 interview conducted by journalist Yuval Ivri for Direction: East, a Hebrew-language magazine about Mizrahi arts and literature, Bar-Moshe said: “I thought and I wrote a great deal in English and in Hebrew, but I did not feel connected to those writings. I love the Arabic language. I was raised in it and I lived in it for 23 years. I read every Arabic book I could find, and I discovered that much of their artistic output was superior to ours; this is particularly the case for literature.”

In response to a question about his relationship to Arabic in Israel, he said: “There was a deep antipathy toward Arabic in Israel when I wrote in that language. I felt as though I were from the enemy camp. I’ve written 10 books in Arabic and not one of them has received any attention. No one in Israeli academia is interested.”

Like many Iraqi Jews, Bar-Moshe was active in the Communist party. He was a journalist, an editor, and the founder of the Arabic-language publication Al Anbaa (The News). He was also an advisor to the Israeli embassy in Egypt, and an analyst for the Voice of Israel’s Arabic language service, which he also directed. His books are about life in Iraq, about longing, the Jewish community, and immigration.

“My father was a strange combination of writer, little boy, and journalist,” said Shemer. “He wrote his stories in a documentary style, very journalistic. They are full of inner dialogues — conversations he had with himself.”

“Leaving Iraq” and “A House in Baghdad” were both translated into Hebrew — the former by Nir Shohat and the latter by Hanita Brand. “Someone told us that a Hebrew translation of one of his books ended up in Iraq, via England, and that someone translated the Hebrew back into Arabic,” said Shemer.

Several articles about “Leaving Iraq” were published in the Arab world, including one written by Mahmoud Abbas. It turns out that the Palestinian leader was friends with Bar-Moshe for many years.

During his first decades in Israel, despite the hostile attitude toward Iraqi Jews and the Arabic language, Bar-Moshe was optimistic about the country’s future. That optimism turned to deep disappointment. Perhaps paradoxically, it was after Egypt and Israel signed the Camp David Peace Accords in 1979 that Bar-Moshe realized, he said later, that Israel was not interested in living in peace with the wider Arab world. The assassination of Yitzhak Rabin in 1995 was the final nail in the coffin of his hopes for Israel. He left the country permanently, moving to England and settling in Manchester, where there was a thriving Iraqi Jewish community. “I felt,” he said in a 2003 interview, “that I did not belong in Israel.”

Bar-Moshe had been an Israeli resident for 20 years when he decided to publish his books in Arabic. In order to understand how unusual his decision was, one must understand a bit of the history.

“I’ll give you the abbreviated version of 1,500 years of history in two minutes and we’ll get to Bar-Moshe,” said the researcher and poet Almog Behar. “Jews were already writing in Arabic in pre-Islamic times; during the Jahilliyah they wrote poetry, which had an enormous influence on Arabic literature.”

Behar continued: “Over the years, under Islam, Jews wrote and created in literary Arabic, as well as in Judeao-Arabic. Saadia Gaon [a prominent Jewish philosopher] wrote in Judaeo-Arabic, and Maimonides [an influential Jewish scholar] wrote most of his commentary in Arabic. During the Nahda, or Arab Enlightenment, which began at the end of the nineteenth century, literary Arabic underwent a modernization process that included Jewish writers. In Iraq, the entire education system shifted to literary Arabic.”

Iraqi Jews in Israel

For the first few years after their arrival in Israel, Iraqi writers like Sami Michael, Shimon Ballas, and Sasson Somekh continued to write in Arabic for Arabic-language publications both in Israel and in Iraq, while gradually shifting to Hebrew.

“But they never gave up entirely on Arabic,” said Behar. “They became prominent translators and professors of Arabic literature. In 1955, they had a very interesting conversation with Emile Habibi, the Palestinian politician and journalist in Israel who founded the Haifa-based newspaper Al Ittihad. As a result of this conversation, the Jewish-Iraqi writers decided that they should write in Hebrew. Habibi, who was a leader in the Communist party both during the British Mandate and after the establishment of the State of Israel, said that literature must serve the masses. If the Jewish masses were reading in Hebrew, then writers must write in that language, in order to connect with them and represent them.”

“Why was Bar-Moshe’s decision to write in Arabic so surprising?” I ask Behar.

“Unlike the other Iraqi-Jewish authors who wrote in Arabic, Ishaq Bar-Moshe and Samir Naqqash did not establish their reputations as professional writers before they immigrated to Israel. Bar-Moshe’s decision to start writing in Arabic in the 1970s, two decades after he arrived in Israel, came as a big surprise to the literary community,” explained Behar. “Sasson Somekh called Bar-Moshe’s books, “literature without a readership.” By the 1970s, there were almost no Jews in Israel who read Arabic for pleasure, and there was close to no chance that anyone in the Arab world would be interested in the literary output of Arabic-speaking citizens of Israel.”

Israel became increasingly hostile to the Arabic language, which was widely perceived as the language of the enemy. Books in that language were ignored by publishing houses as well as academia. Even the literary prizes were given in a different category: Bar-Moshe won the Prime Minister’s Prize for Arabic Literature, along with writers like Emile Habibi, rather than simply the prize for Israeli literature. Most of his books were published privately (in Bar-Moshe’s case, by the Sephardic Jewish Community in Jerusalem), while the task of translation often fell to family members.

“That was part of the tragedy of Arabic,” said Behar. “Because they were considered so marginal, family involvement was essential; there was no other source of translators.”

Shemer says that her father’s last book, “Two Days in June,” was translated posthumously. “My mother had to translate it from Arabic, because I don’t speak the language.”

Turning loss into gain

The mass transition from Arabic to Hebrew became a process of erasure and collective forgetting, said Behar. Jews who were native Arabic speakers refrained from reading in their own language because the culture of taboo made them feel it was a shameful act, so the language was not passed on to the second and third generations. Today, the average graduate of an Israeli public school education has no idea that Arabic was once a Jewish language. Only a tiny minority of Israeli Jews — less than one percent of the population — speak Arabic.

The Jewish-Iraqi writers who continued to write in Arabic after they arrived in Israel are almost completely unknown today, according to Behar. He has been teaching courses on Mizrahi literature for almost 15 years, but says his students — the vast majority of whom sign up for his courses because they are interested in the subject — have never heard of Iraqi writers like Shimon Ballas, who was once a luminary of Israel’s Arabic-writing Jewish literary community.

The cultural and activist revival among third-generation Mizrahi Jews has not skipped Bar-Moshe. A few months ago, a short film about Bar-Moshe was released, with the title “Three Things That Were Lost.” His granddaughter Na’ama Shohat produced the film as her senior thesis for the Screen-Based Arts Department at Jerusalem’s Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design. In the film, which she dedicates to her grandfather, Shohat recalls the many excerpts from his books that speak of loss, of exile, and of a longing to return to a place that has changed beyond recognition.

“I didn’t know him, and this was my opportunity,” said Shohat. “My sense of belonging and yet not belonging makes me feel very connected to my grandfather. His book reflects a loss of home, and also my own loss of my grandfather. This emptiness is the source of art — the film is my way of turning loss into gain.”

In Iraq, too, the younger generation has been trying over the past decade to revive its forgotten literary heritage. Saddam Hussein and his predecessors wanted to erase every last trace of the country’s Jewish presence, explained Behar. “When they played songs by Jewish artists on the radio, for example, they used to attribute them to “unknown composers.””

Since 2003 and the fall of Saddam Hussein, Iraqis are imagining a multi-cultural alternative vision for their country; this has led to a growing interest in its Jewish past. Iraqi-Jewish literature has returned to the academic canon, while articles and opinion pieces on the subject are published in prestigious publications.

“It didn’t happen in their lifetime,” said Behar, “But today those writers have been brought back into the fold.”

This article was first published in Hebrew on Local Call. Read it here.