The Education Ministry seems to be doing all it can to give teachers the feeling that deep, honest conversations about democracy and equality are not welcome in school.

By Gil Gertel

The director-general of the Education Ministry published an amendment to its “Educational Discourse on Controversial Issues” guidelines last week. The reason? To impose restrictions on guest lecturers who come and speak to students. The amendment does not propose any tools for selecting lectures, instead it creates ambiguity intended to frighten principals and teachers. Two studies published over the last few weeks confirm the trend: fear has spread on all levels, from teachers to heads of local authorities, over dealing with humanistic and democratic education. We have reached a point in which democracy is seen as a “complex and explosive concept.” Israeli society is afflicted with a severe anti-democratic disease.

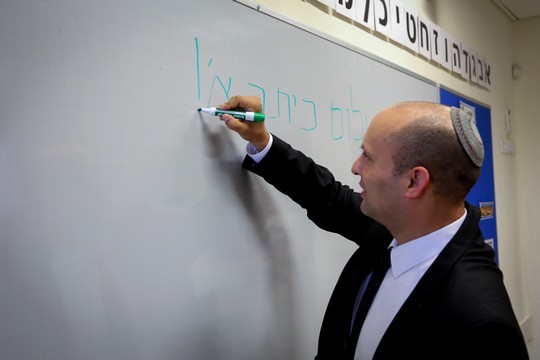

Exactly one year ago, Education Minister Naftali Bennett banned members of Israeli anti-occupation group, Breaking the Silence, from speaking to students. This, of course, was nothing more than spin. In Israel the education minister does not decide who can or cannot enter schools, certainly not by arbitrary declarations against an organization that he dislikes. Bennett knows this, and thus thoroughly examined the work of educators, who for the past year have tried their best to figure out how to please the honorable minister. These professionals cannot make a decision vis-a-vis government bodies — instead they are to establish criteria to filter out those who must not be allowed to enter school grounds.

The director-general’s guide on educational discourse, in its original version, was intended to push teachers to deal with controversial topics. The directive called to remove the barriers of fear, to guide teachers, and emphasize the importance of such discourse. Here is a positive example from the guide:

The goal of this guide is to encourage teachers to hold discussions on questions of personal identity and civil discourse on controversial topics that raise moral dilemmas.

The education system is interested in educating its students to make value-based judgements, to develop a public and political consciousness, to become active on social and political issues, and to take a stand. Thus it seeks to promote a principled and critical discourse, as well as a range of opinions in the framework of civil education that is common to all sectors of society.

The updated version published last week included a paragraph on the entry of guest lecturers:

Entry is forbidden to external groups and speakers whose activities, among other things, promote racism, discrimination, incitement, calls for violence, and party propaganda that are not in accordance with the director-general’s guide, as well as discourse that harms the legitimacy of Israel as a Jewish and democratic state. Moreover, entry will be forbidden to speakers who have been convicted of a crime of moral turpitude, or any group that violates state laws or any body whose activities undermine the legitimacy of state bodies (such as the Israel Defense Forces and the courts).

Ambiguity is frightening

Many of these guidelines state the obvious, such as the requirement to follow the law. For this there is no need for a new guide. But among the obvious guidelines hide two ambiguous, underlying dictums, which must not be used when choosing guest lecturers. The first one forbids “discourse that harms the legitimacy of Israel as a Jewish and democratic state.” Who will decide the boundaries of such legitimacy? According to this dictum, Bennett’s infamous statement, according to which “we must give our lives” for the annexation of the West Bank, is illegitimate. In my eyes, his suggestion is neither Jewish nor democratic.

The second dictum forbids allowing “any group whose activities undermine the legitimacy of state bodies, such as the Israel Defense Forces and the courts.” Is this guideline intended for groups who undermine the existence of those bodies, or merely specific activities those bodies partake in? For instance, I believe that the army’s activities in the occupied territories are not legitimate, but I say this in order to strengthen its legitimacy — as an army that protects a state, not as an occupation army. And what do we do with all the groups led by right-wingers, which harm the legitimacy of the court system on a daily basis?

These ambiguous guidelines do not prevent Breaking the Silence from lecturing, nor do they allow far-right groups such as Im Tirzu to speak to students. Principals cannot actually use these guidelines to make decisions ahead of time about what is or is not allowed. And what principal in her or his own right mind would take the Education Ministry to court? Therefore, it is safe to say that the new directives are not intended to assist principals in deciding who can or cannot be invited. Instead, they are designed to frighten principals and teachers from inviting groups in the first place.

Thus the guide completely guts the concept of “promoting a range of opinions,” turning it into an ambiguous slogan that scares principals and teachers from initiating any educational activity.

What’s so scary about democracy?

Yet teachers and principals did not wait for the new guidelines from the director-general to know something rotten was taking place long ago. This year’s Dov Lautman Conference on Educational Policy, which took place two weeks ago, focused on partnership and democracy in Israel. In the run up to the conference, a team headed by Professor Eran Halperin conducted a study on the ways in which teachers and parents handle controversial subjects in school. According to the study, teachers assumed that the Education Ministry, and especially parents, are not interested in teachers dealing with these topics in the classroom. For instance, 87 percent of teachers claimed that it is important to discuss relations between Jews and Arabs in the classroom. Yet only 47 percent think that this is expected of them, and only 23 percent think that parents expect this of them.

Surprisingly, it turns out that the parents’ position is entirely different. Ninety-one percent of them actually want their children to learn about Jewish-Arab relations, and 74 percent of them think that Jewish students need to learn the Palestinian narrative. Despite the parents’ high expectations of the education system, only 29 percent of them think that teachers actually bring these issues into the classroom.

It turns out that we have a double miscommunication: the teachers want to teach, but think this is not expected of them; meanwhile the parents want their children to learn, yet think teachers are refraining from teaching. Perhaps nobody wants anything, and everyone simply prefers to place the responsibility on someone else.

One may ask why teachers are concerned. After all, the original version of the guide supports breaking down barriers of fear. Here is the simple answer: 73 percent of teachers reported that they do not even know of the guidelines. That is, even the Education Ministry is saying two different things: on the one hand, it is important to discuss controversial issues with students, on the other hand it does not even distribute the guidelines that encourage teachers to do so.

Another study looked at the positions taken by heads of local authorities in Israel vis-à-vis democracy in school. They, too, claimed there is great significance in promoting democracy in schools, especially in light of what they called “the weakening of democratic foundations in society.” However, in their view this does not fall under the role of the local authorities, but rather is the sole responsibility of the Education Ministry. Heads of local authorities stated that democratic principles are not included in the Education Ministry’s “set of principles,” and often contradict the “spirit of the ministry.” Democracy is seen by the authorities’ heads as a “complex and explosive concept,” and they fear that it may raise opposition among residents. There are even those who believe that “educating for democracy does not answer the needs of the residents.”

A year and a half ago I published an article [Hebrew] on the weakness of democracy-based education, following the publishing of a study that focused on high school principals. The picture hasn’t changed much since then; the problem is not with the education system — Israeli democracy is sick, and its sickness can be felt in schools.

Parents, teachers, principals, heads of local authorities, clerks at the Education Ministry — all of them are Israeli citizens. They, like all of us, lack the deep foundations of a humanistic and democratic outlook. After all, what is everyone afraid of? Of declaring, without fear, that racism is bad, that democracy means protecting the rights of minorities, and that Palestinians also have a narrative. There, I said it. It wasn’t so hard.

Gil Gertel is an educator and a blogger at Local Call, where this article was first published in Hebrew. Read it here.