At Israel’s request, Twitter is blocking Israelis from viewing certain tweets published overseas. Similar take-down notices have been sent to other international online platforms, the Justice Ministry confirms.

Israeli authorities are taking steps to block their own citizens from reading materials published online in other countries, including the United States.

The Israeli State Attorney’s Office Cyber Division has sent numerous take-down requests to Twitter and other media platforms in recent months, demanding that they remove certain content, or block Israeli users from viewing it.

In an email viewed by +972, dated August 2, 2016, Twitter’s legal department notified American blogger Richard Silverstein that the Israeli State Attorney claimed a tweet of his violates Israeli law. The tweet in question had been published 76 days earlier, on May 18. Silverstein has in the past broken stories that Israeli journalists have been unable to report due to gag orders, including the Anat Kamm case.

Without demanding that he take any specific action, Twitter asked Silverstein to let its lawyers know, “if you decide to voluntarily remove the content.” The American blogger, who says he has not stepped foot in any Israeli jurisdiction for two decades, refused, noting that he is not bound by Israeli law. Twitter is based in California.

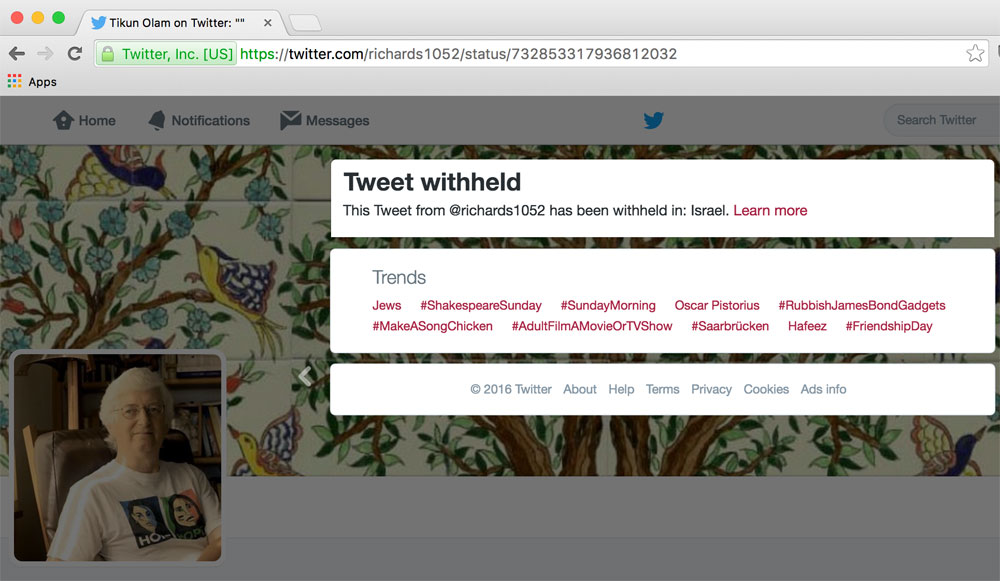

Two days later, Twitter sent Silverstein a follow-up email, informing him that it was now blocking Israeli users from viewing the tweet in question. Or in Twitter-talk, “In accordance with applicable law and our policies, Twitter is now withholding the following Tweet(s) in Israel.”

The tweet is still available from American and non-Israeli IP addresses, but viewed from Israel, it looks like this:

Because I am writing this from Israel, I am legally forbidden from telling you what Silverstein’s original tweet said. I can’t even tell you the specific legal reason why I can’t tell you what I can’t tell you.

What I can say is that as the use of military censorship in Israel has become less common and less sweeping over the years, authorities are increasingly using court gag orders to control the flow of information in the country. Often times those gag orders cover the very existence of the gag order itself.

+972 has seen Twitter’s correspondence with Silverstein, but not the Israeli Justice Ministry’s specific request of Twitter. Justice Ministry spokesperson Noam Sharvit denied, however, that Israel demanded any concrete action of Twitter in Silverstein’s case, only that it “brought the violation of the gag order to the company’s attention.”

A page on Twitter’s website explaining the practice of “withholding” content stresses its commitment to being as transparent as possible about its censorship. The company notes that it has partnered with Lumen to make “requests to withhold content” themselves available to the public.

The database of take-down notices provided by Lumen and Twitter, however, does not include the publication of a single request that either mentions or originates from Israel or the Israeli government. Therefore, it is impossible to know with absolute certainty exactly what the Israeli request entailed.

Facebook, on the other hand, provides public data about the number of requests to restrict content in Israel “alleged to violate harassment laws, as well as content related to Holocaust denial.” Facebook says it restricted 236 pieces of content in Israel in the second half of 2015, the most recent period for which data is available.

Israeli legal authorities censoring information published inside Israel’s geographic and legal jurisdiction might seem like standard practice, albeit morally and ethically objectionable. Attempting to block information published overseas, however, is more akin to the type of censorship we’re used to hearing about in countries like China, Turkey, Syria, and Iran.

In most countries where internet censorship is most prominent, the practice is most commonly associated with the suppression of political dissent and attempts to control the free flow of information, upon which democracy and healthy political debate are fully dependent. Those who want to circumvent internet censorship, however, have an array of technical options for accessing blocked content.

This development also comes as the Israeli government has declared non-violent political activists as a high-priority target. Earlier this week, the public security minister and interior minister announced their intentions to deport foreign anti-occupation and BDS activists, and make Israeli citizens whose political activism includes nonviolent tactics like boycotts, “pay a price.”

Most of the public discussion surrounding internet censorship in Israel in recent months has focused on alleged Palestinian incitement to violence, which, at least at face value, can be interpreted to be a matter of public safety. Enforcing a gag order, however, is the state attempting to control the flow of information, plain and simple.

Which is not to say that there are not legitimate uses of gag orders, for instance, to protect minors and victims of certain crimes. According to the Israeli Justice Ministry spokesperson, Silverstein’s tweet indeed included information that could be used to identify a minor who was the victim of a sex crime.

In a more general sense, however, when a state has demonstrated its willingness to use gag orders and censorship to cover up its own crimes (the Bus 300 Affair and evidence of extrajudicial killings exposed by Anat Kamm) and to stifle legitimate free speech that challenges an undemocratic military regime, it becomes a moral imperative to fight all forms of censorship.

One recent and unfortunate example of how gag orders and censorship can be used to obfuscate justice, and at the very least give the impression of a coverup, is the shooting deaths of two Palestinian siblings by Israeli security contractors at the Qalandia checkpoint in late April of this year.

Palestinian witnesses said that the two, who were said to have knives in their possession, posed no immediate threat to the Israeli guards or police officers stationed at the checkpoint. Israeli authorities, however, have refused to release CCTV footage of the shooting, and placed a sweeping gag order on the investigation and the identity of the suspects. On August 2, the gag order was once again extended until August 31 — 126 days since the shooting.

It may have been possible to justify the original gag order, which was supposed to last only one week, with investigatory considerations. More than four months later, however, it is hard not to question what it is police have to hide.

***

Asked how many take-down requests have been sent to overseas social media platforms, the Israeli Justice Ministry spokesperson responded:

The Cyber Division, works, among other activities, with various internet providers to remove content that violates Israeli law, including the terms of use of the providers themselves. The division acts against forbidden content like the publication of pedophilia content, incitement to violence and racism, and publications that violate judicial or statutory gag orders. It should be noted that in the terms of use of most providers, the providers themselves declare that they comply with state orders. As part of the division’s activities, a number of providers have been approached in recent months with requests to remove such content, in various cases.

Asked whether it has also sent international media outlets requests to block certain content from Israeli readers, the Justice Ministry spokesperson said: “there have been such requests in the past which were sent to foreign providers, also including [publications] that were published in Israel.”

Read this article in Hebrew on Local Call.