By Fady Khoury

The decision by Israel’s Supreme Court to keep the Nakba bill intact demonstrates its capitulation to rightwing pressure and increasing struggle to survive as an independent body.

The High Court of Justice (HCJ) on Thursday dismissed a petition submitted by Adalah, the Legal Center for Arab Minority Rights in Israel, and the Association for Civil Rights in Israel, challenging the constitutionality of the Budget Foundations Law (Amendment No. 40) 5771 – 2011 – commonly known as the Nakba Law. This law authorizes the Minister of Finance to financially penalize government-funded bodies that engage in activities that amount to “rejecting the existence of the State of Israel as a Jewish and democratic state” or “commemorating Independence Day or the day of the establishment of the state as a day of mourning”.

About the Nakba:

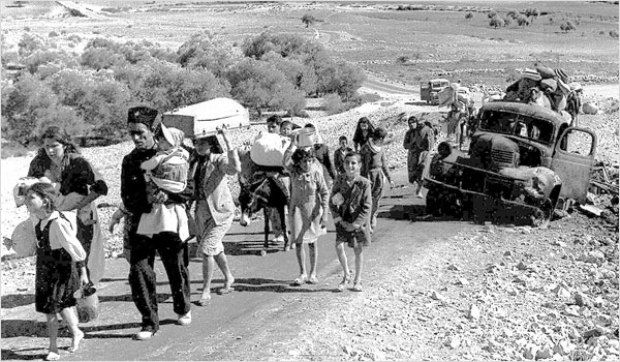

Nakba Day marks the events of 1948 and their effects on the Palestinian society, which are described in the introduction to the book titled “NAKBA: Palestine, 1948, and the Claims of Memory”, as follows:

“The 1948 war that led to the creation of Israel also resulted in the devastation of Palestinian society. At least 80 percent of the Palestinians who lived in the major part of Palestine upon which Israel was established – more than 77 percent of Palestine’s territory – became refugees. […] The minority of Palestinians – anywhere from 60,000 to 156,000, depending on the sources – who remained behind became nominal citizens of the newly established Jewish state, subject to a separate system of military administration by a government that also confiscated the bulk of their lands.[…] For Palestinians, the 1948 war led indeed to a ‘catastrophe’. A society disintegrated, a people dispersed, and a complex and historically changing but taken for granted communal life was ended violently. […] After 1948, the lives of the Palestinians at the individual, community, and national level were dramatically and irreversibly changed.” (p. 3).

As an important historic event that had (and still has) an enormous impact on Palestinian reality, society and collective status and identity, Nakba day is annually commemorated by a number of local authorities, schools, and political parties. The commemoration events vary. Some focus on the artistic value through screening movies, holding concerts, or reading the poetry of Palestinian national poet Mahmoud Darwish or other relevant materials. Others concentrate on historic and political aspects, which are represented through experts’ discussion panels (historians, politicians, anthropologists, sociologists…), political speeches or marches. Most of events are likely to include some combination of these activities.

The Nakba Law and HCJ’s decision:

The law seeks to prevent Palestinian citizens from commemorating Nakba Day. In previous versions of the bill, it was proposed to define commemorating Nakba Day as a felony punishable by imprisonment, but the Ministry of Justice intervened and suggested a more moderate version, which went into effect in March 2011.

The Nakba Law clearly limits freedom of speech, as it deems some forms of speech punishable by a penalty that could reach up to three times the expenditure of the commemoration in question. The bottom line is that the law makes commemorating the Nakba illegitimate and unacceptable, an activity that requires regulation in the form of penalization.

The HCJ’s ruling this week held, among other things, that since the law has not yet been applied to any cases, , the inquiry into its constitutionality would be premature.

This ruling is baffling. The HCJ is the authorized interpreter of the law and the Basic Laws as the constitutional norms in the Israeli legal system, decides to wait and see how the executive will apply it. This could be legitimate in cases that involve a statute that is open to several interpretations, where the court waits to see which will be chosen. In such cases, the unconstitutionality of the statute does not stem directly from it, but rather from its application by the executive branch. However, in cases in which the mere existence of legislation creates an infringement on human rights or the clear potential of such an infringement, it is within the judicial branch’s power – and some would even say duty – to examine the constitutionality of the said legislation.

This approach was applied by the HCJ not too long ago in the famous decision regarding the constitutionality of the prison privatization law, in which the mere act of transferring the state’s authority for managing a prison to a private organization which is motivated by profit would severely violate prisoners’ basic human rights to dignity and freedom. In its argument, the state claimed that the petition was premature, since it is not necessarily the case that human rights would be violated. The court dismissed these arguments and decided that the legislation was in fact unconstitutional, without waiting to see whether its application would lead to a different conclusion.

As in the prison privatization case, the notion of inherent human rights violations applies to the Nakba Law. Even though the Nakba Law targets government-funded bodies only, it sends a clear message that in all cases, commemorating the Nakba is illegitimate and to be frowned upon. Thus, the effects of the law are far more wide reaching than just those cases to which it directly applies. It renders illegitimate the collective memory and narrative of the Palestinian citizens of Israel, and by its mere existence, it violates the Palestinians’ constitutional right to dignity.

It also violates their freedom of political and cultural expression in two ways: firstly, by limiting the freedom of expression of the affected institutions; second, through the law’s chilling effect on bodies and individuals who may not even fall within the scope of the law but might refrain from engaging in activities commemorating the Nakba due to the stamp of illegitimacy this day has incurred.

The law also infringes on the right to equality. The schools of Palestinian citizens are no longer allowed to commemorate the Nakba, since according to the law it is “marking Independence Day… as a day of mourning.” Nor would they be allowed to present the pupils with the Palestinian narrative, since it falls within the scope of “denying the existence of Israel as a Jewish and democratic,” while the Jewish education system is free to instill and cultivate the Zionist narrative and values.

Local authorities are now forbidden from holding events commemorating Nakba Day, out of fear that it could lead to withholding government funds necessary to its survival. Withholding government funds thus punishes pupils and residents, even should they choose not to participate, since fewer funds means fewer services. The law thus contains a component of collective punishment.

All of these violations are implied though the mere existence of the statute, rendering its implementation irrelevant. Whether the executive decides to apply it only to certain bodies or to limit the fine, those who are subject to its application will still suffer a violation of the above-mentioned rights. Therefore, it is clear that the HCJ simply avoided the constitutional examination of the Nakba Law.

Through the employment of different avoidance techniques, the judicial branch avoids examining politically-sensitive matters that may affect its relationship with the other branches of government. In the case of the Nakba law, the HCJ was conflicted. On the one hand, determining that the law is constitutional contradicts previous rulings, and would probably invite extensive criticism from the human rights community and the legal community. On the other hand, ruling that the law is unconstitutional and thus void would anger the right-wing coalition that initiated the law and is presently pursuing legislation that would limit the power of the judicial branch.

The Court’s decision in the Nakba Law case demonstrates that the recent threats to diminish the Judicial Branch’s powers are already taking effect, in that the authority responsible for guaranteeing and safeguarding human rights has turned into an institution that is focused mainly on its own survival.