To avoid being transferred to a garbage dump in East Jerusalem, the villagers of Khan al-Ahmar will have to convince three other Bedouin communities to evacuate the area. After that, they can live near a wastewater site.

By Hagai El-Ad

Since the mid-1970s, Israel has been working to drive Palestinians out of the West Bank area which lies east of Jerusalem. Special efforts have been invested in emptying the “Ma’ale Adumim bubble” — the sizable swath of land extending eastwards, from the outskirts of East Jerusalem about halfway to Jordan, to be enclosed by the planned separation barrier – of Palestinians. These efforts are explicit, ongoing, and violent.

Nonetheless, the state’s recent brazen admission of its intentions before the High Court of Justice, in its response to a new petition against demolishing the village Khan al-Ahmar, is a new low.

To justify the forcible transfer of Palestinians out of their homes, the state peppered the court with formalistic arguments based on the “rule of law,” context be damned. The residents of Khan al-Ahmar were accused of “building illegally,” as though Israel leaves Palestinians in Area C any option to build legally.

They were faulted with living too close to Route 1, which connects Jerusalem with the Dead Sea, conveniently ignoring the fact that they were there years before the road was ever built, and are willing to move 100 meters to the north, away from the road, to placate the state. These and other absurd legalisms were enlisted in order to avoid spelling out before the court Israel’s aforementioned true motivation: cleansing “the Ma’ale Adumim bubble” of Palestinians.

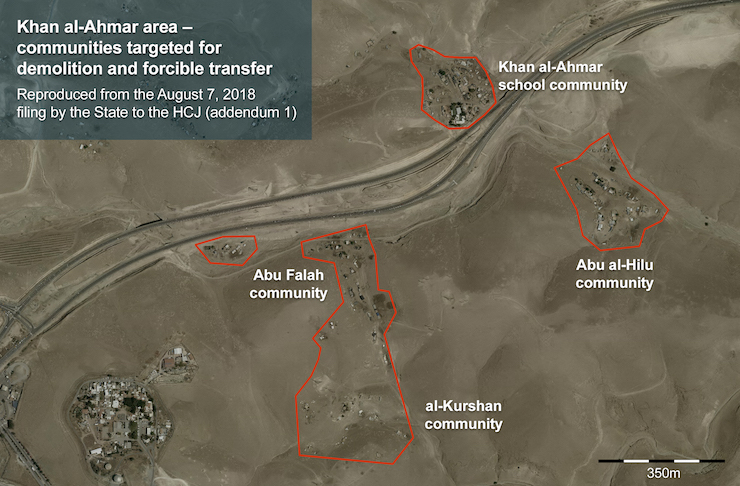

Yet this underlying motivation becomes ever more explicit as the state, in its response to the new petition, suddenly tied the future of Khan al-Ahmar to its neighbors. Of course, we are not speaking of the settlers who live nearby, but rather three other Palestinian communities that are now somehow also slated for expulsion. The state did not even bother to come up with an excuse for this, but simply declared that the planned expulsion now includes not “only” the 30-plus families of Khan al-Ahmar, but the entire “four compounds of the Jahalin Abu Dahuk tribe, comprising some 80 families” — that is more than 400 people in total.

Doubling the number of people to be expelled was presented as a precondition to offering Khan al-Ahmar an alternate relocation site, this time next to a wastewater treatment center: “This plan will be promoted in keeping with all the provisions of the law, and advancing it will be contingent upon having all the relocating families sign an affidavit stating that they commit to evacuating the Khan al-Ahmar compound independently and without violence.”

In other words: the state is ready, and has been for more than two months, to transfer Khan al-Ahmar’s families directly to the initially proposed “permanent site” near the Abu Dis garbage dump. It has emphasized it is “in the final stages of preparation for fulfilling the final demolition orders for the Khan al-Ahmar compound.” But since a new petition was filed anyway, why not try and leverage it to transfer even more Palestinians from the “Ma’ale Adumim bubble?” Never mind that they have nothing to do with the petition. Never mind the mind-boggling cynicism of expecting a Palestinian community to persuade hundreds of other Palestinians to join them in “consensually” abandoning their homes, supposedly for their own good. Never mind how explicit it makes the state’s true intentions: to dispossess and expel as many Palestinians as possible from the area marked for cleansing.

Over the years, and through dozens and dozens of petitions by various Palestinian communities, the High Court deepened the breach of justice it set by its failure to rule from the outset against the expulsion of protected people from their land. This failure became an outright disgrace on May 24 this year, when the justices green-lighted forcible transfer — a war crime — in the case of Khan al-Ahmar. The new petition, filed by a group of Palestinian attorneys, may be the court’s last chance to look reality in the eye, to stop serving the state’s policy by accepting formalistic quibbling, and prevent this crime from taking place.

On the ground, the authorities are subjecting all the Palestinian communities in the area, including Jabal al-Baba and Abu Nuwar, to incessant, violent pressure, mostly through constant threat of demolitions and the denial of basic infrastructure. Israel’s endgame here is to remove all these communities and use the separation barrier to de-facto annex the “Ma’ale Adumim bubble” — devoid of Palestinians. Of course, it intends to also retain control over the areas beyond the separation barrier: the enclaves in which it will graciously allow isolated islands of Palestinians to continue with what remains of their lives.

How foul is this policy? From the state’s perspective, the residents of Khan al-Ahmar can “choose” to live by the Abu Dis garbage dump — or by the a sewage treatment plant, which happens to serve, among others, the settlement of Kfar Adumim: the very same settlement whose residents repeatedly petitioned the High Court to have their Palestinian neighbors kicked out. This is Israel’s plan: the Palestinians who were the neighbors of Kfar Adumim will either become the neighbors of that settlement’s sewage or of Jerusalem’s garbage. It does not matter — as long as the area is cleansed.

Hagai El-Ad is Executive Director of B’Tselem. This article was first published in Hebrew on Local Call. Read it here.