Faced with the most striking evidence, the Israeli media continues to treat the Palestinian version of the killings as a fabrication, demanding more and more evidence of wrongdoing; that is how the public is taught, day by day, that the reality of occupation isn’t worthy of its attention.

Ever since I left working on the sports pages and began dealing with current affairs, I remember myself trying to initiate stories on the Palestinian issue. Writing about the West Bank and Gaza seemed to me the most crucial contribution an Israeli paper can make. Besides, there were always great stories, of all kinds, in the occupied territories.

Israelis walk around feeling they know everything about the occupation and the conflict, but my impression has always been that this more of a defense mechanism than a fact of life. I often meet internationals who have traveled on the ground and know their way around better than most of the Jewish public. The more I deal with the occupation, the more I understand how much more I have to learn.

But the real problem in the media organizations I worked for was never a shortage of knowledge or good stories, but rather, self-censorship. In the most grotesque moments, the orders came straight from the top. I specifically remember an op-ed by our publisher at Maariv, Ofer Nimrodi, published during Cast Lead. In it Nimrodi apologized to his readers and to the army’s soldiers and generals, for a text by one of our regular columnists that criticized the IDF’s conduct.

Another time, the late editor of Maariv, Amnon Dankner, stood on the newsroom floor screaming at the editor of the the weekend magazine: “Israelis don’t want a picture of an Arab terrorist with rotting teeth on the front page of their holiday paper!” The thing that made him jump was an exclusive interview one reporter got with Laila Khaled in Amman.

Things got worse after Cast Lead. After the operation ended, we sat – the magazine’s editor and myself – with the heads of human rights organization B’Tselem. They presented us with the findings of their investigations, documenting numerous cases of civilian casualties, which could have been avoided, or at times – even seemed intentional. The attempt to turn this into a feature story was buried under excuses from the paper’s editors: it was a non-item, not interesting enough, not new, and so on. We all began to seriously deal with some of those cases – and the IDF even ended up putting soldiers on trials – only following the Goldstone Report and some publications in the international media.

The threshold for Palestinian stories has been on the rise ever since. To get a story published that actually dealt with Palestinians, it needed to be increasingly unique. Most of the time, there wasn’t even a real need to censor anything. Everybody in the paper understood.

Readers hated such stories, too. At a time when newspapers are collapsing, this is no small thing. Israelis often ask why their own human rights organizations turn to the international community with their stories and findings, but they should actually be wondering why neither the public nor the Hebrew-language media are interested in this material.

For a story to break into the mainstream conversation, it had to really have rare qualities: say, a blonde Danish guy who is rammed with a rifle by an army colonel during a bicycle protest in the Jordan Valley. Plus, there was a need for awesome media, preferably video. Testimonies by real people – which has always comprised the heart of journalistic writing – account to nothing when it comes to Palestinians. Photos are only slightly better.

If one thought that video cameras or mobile devices would solve this issue, as far as the Israeli media is concerned, not much has changed. A new myth emerged – that most Palestinian material is fabricated, or “manipulatively edited,” or any other nonsense that is meant to cast doubt on the entire event, and not less important – to deprive it of any context, as if the protest is not taking place under occupation, as if there is no reason for this “riot,” and so on.

There is always the chance that a video is manipulated or fabricated, including the current clips from the protest outside Ofer Prison – the one showing the killing of two Palestinian minors. Yet such fabrications are the rare exception, not the norm a journalist encounters. Most videos are real, most witnesses are reliable.

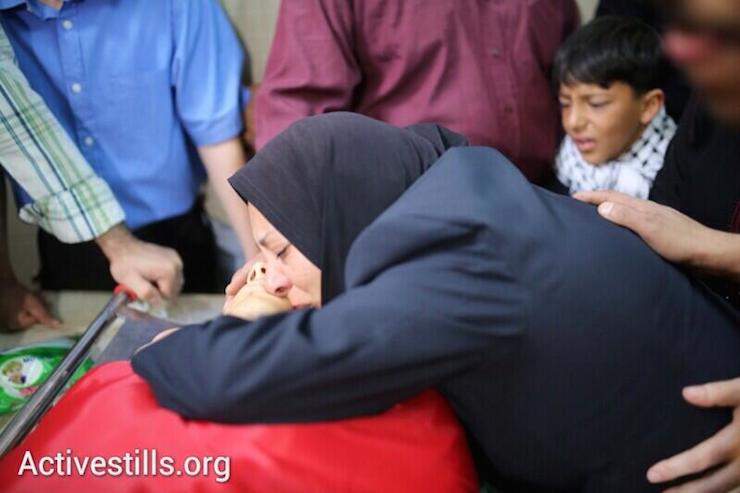

Specifically, there are 21 gigabytes of videos from the Beitunia shooting, taken from four security cameras; there are hours of tape from that day. There are the real bodies of two dead Palestinians. There are the reports from the hospital they were taken to. Even Israel doesn’t doubt the basic facts – that a couple of teens were killed in that protest.

And yet, when it comes to the Israeli media, the common response was rather skeptical. On Channel 10, Yaron London – not a raving right-winger – actually concluded that this was a fabrication. Defense Minister Moshe Yaalon and the headline in Israel’s most widely read paper, Yisrael Hayom, said pretty much the same thing. The other important daily, Yedioth, spoke of “a controversy.” The military correspondent in the widely watched Channel 2 News, Roni Daniel, sounded doubtful. They all chose to be blind, and to hell with their responsibility to the public.

This is why the Israeli mainstream seems to be divided between those who doubt the Palestinian version and those who think that shooting at unarmed protesters is not such a bad idea. This is why political decisions are taken in a public atmosphere that is as mean as it is ignorant. The results are as catastrophic as one could expect.

Two more notes: (a) because of the sensational character of the West Bank coverage in the Israeli media, directly resulting from the rise of the emotional and journalistic threshold to absurd levels, the “coverage” becomes an aggregation of bizarre, unrelated incidents, most of them not that severe. Someone is hit, another guy is threatened with a loaded gun – the sort of stuff you see in every city. Palestinians are killed almost every week in the territories, homes are demolished on a regular basis; people are arrested, beaten and humiliated every day. But if you ask the average Israeli, he thinks that what takes place in the West Bank is not that different from the pushing and shoving at the entrance to a rock concert anywhere else. That’s what they see.

(b) As far as the media’s dealings with the security forces goes, it’s the exact opposite: the bar is constantly lowered. The most heavily edited, most manipulative clips shown on Israeli television in recent years were from the Mavi Marmara. The IDF confiscated all the media from the numerous journalists on board, but released only several clips of few seconds each, edited, marked with arrows and other graphics, put in slow-motion at times. Did any of the journalists, local and international, who aired these clips bother to demand the release of the raw footage? Did anyone ask “what happened prior to those images?” as they do now?

At times, those clips only served the political needs of senior generals. On the day the army’s chief of staff testified before the committee investigating the raid on the Mavi Marmara, and “by pure coincidence,” the IDF Spokesperson released a (heavily edited) clip showing MK Hanin Zoabi confronting soldiers on board the ship. You could guess what the center of the media’s attention was that day.

Related

WATCH: Footage shows Israeli army’s killing of two Palestinian teens

Human rights NGO: Investigate senior IDF officers over Ofer killings