For the first time in over 30 years, a proper Kahanist party could be entering the Knesset. But is the rise of a party that advocates for Jewish supremacy, theocracy, and ‘total war’ as unprecedented as the outcry has suggested?

The last week has been an eventful one in the annals of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s dalliances with the racist ultra-right. Fresh from upsetting his authoritarian, antisemitic allies in Europe by failing to adequately maintain his recent efforts at Holocaust revisionism, Netanyahu has now paved the way for homegrown Israeli fascists to take their place — once again — in the Knesset.

The prime minister’s overtures to the Jewish Power (Otzma Yehudit) party are not, in the context of his political character, surprising. His readiness to rely on white supremacists and ultranationalists abroad to prop him up provides ample evidence of the types of characters he’ll make common cause with. It has also long been clear that there are very few depths Netanyahu will not plumb when his perch at the top of Israeli politics is under threat.

And that threat does, with the national elections in April looming, feel real. Faced with some of his current coalition partners failing to pass the electoral threshold, Netanyahu successfully lobbied the Jewish Home party to team up with Jewish Power, which brings the real prospect of an explicitly Kahanist party entering the Knesset for the first time in over 30 years.

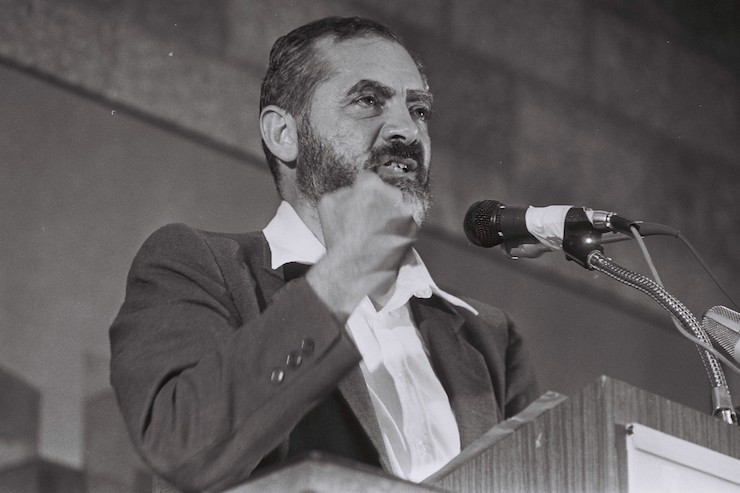

Rabbi Meir Kahane, who founded the Jewish Defense League and for whom the Kahanists are named, was a fascist. He wanted to remake Israeli society by expelling Palestinians and making Jewish law the law of the land. He believed in Jewish supremacy, was fixated on ethnic purity, and declared antisemitism in the diaspora necessary in order to prevent assimilation. Violence and militarism were, for Kahane, instruments through which to ensure national rebirth.

The JDL manifestos Kahane wrote in the 1960s and ‘70s in New York contained seeds of this fascist ideology. The policy platform his party, Kach, ran on in the 1984 Israeli elections, and which got him elected, was explicitly fascist. It’s important to state this unequivocally. Referring to ‘Kahanism’ without naming its ideological pedigree makes it impossible to have an honest discussion about this latest evolution in Israeli politics.

From fringe to mainstream

Kahane undoubtedly shifted the parameters of Israeli discourse during his turbulent parliamentary career. Among Kach’s principles and policies were those calling for mass expulsions of Palestinians; the annexation of the West Bank, Gaza, the Golan Heights, and the Sinai; and a ban on marriage, and all sexual contact, between Jews and non-Jews — punishable by prison sentences ranging from five to 50 years. This last point was a particular obsession for Kahane: his political rallies in Israel regularly featured histrionic, concocted tales of scores of Jewish girls kidnapped and taken to Palestinian villages; and during a Kach election broadcast in the 1980s (delivered, curiously enough, in English), he warned of “the destruction of Israel not through bullets but through Arab babies.”

His party’s security principles, meanwhile, continued the theme of righteous Jewish violence that informed his writings for the JDL — violence that he invested with both a biblical lineage (Bar Kokhba, Judah Maccabee) and a redemptive potential (an end to Jewish oppression). His Second Amendment-style JDL slogan, “Every Jew a .22,” made aliyah in the form of a call to give the Israel Defense Forces a “free hand” when dealing with Arabs — in other words, a shoot-to-kill policy with no questions asked.

Among Kahane’s other visions were an ethnically-segregated education system, which would be focused on teaching love for Israel and the Jewish people; a small government with minimal bureaucracy that would allow the flourishing of a “Jewish economy”; and the outlawing of the Israeli Communist party.

The list goes on. Above all, Kahane sought the dismantling of what passed for Israeli democracy, calling for a state based on Jewish religious law. Indeed, he believed that Judaism and “Western” democracy were fundamentally incompatible, although he was not against the temporary use of democratic institutions in order to further his other political goals.

As much as almost the entire spectrum of Israel’s political establishment pronounced their shock at Kahane’s rhetoric and actions, even going so far as to boycott his speeches in the Knesset, his popularity in Israel only rose after his election. Having failed to make the electoral threshold in 1973, 1977 and 1981, and after winning a single seat in the 1984 elections, Kach was projected to win four seats or more in the 1988 elections. The Israeli Election Commission barred Kach from running on the grounds that the party’s platform incited racism, but by then Kahane’s talk of mass expulsions was already being aired by mainstream parties in the Knesset.

Waging ‘total war’ against Israel’s enemies

Kahane was assassinated in New York in 1990, and Israel outlawed Kach as a terror organization in 1994 (the U.S. followed a year later). But his movement lived on in Israel: the core members of Jewish Power — Baruch Marzel, Itamar Ben-Gvir, Michael Ben-Ari, and Benzi Gopstein — are all disciples of Kahane and former Kach activists. Between them, they have variously persecuted Palestinians, leftists, African asylum seekers, and the LGBTQ community.

Jewish Power’s 2019 election manifesto bears a resounding resemblance to Kach’s platform. The party proposes implementing Jewish law as the law of the land, and having an education system that teaches love of Israel and the Jewish people. It promises “total war” against “Israel’s enemies,” and seeks the annexation of the West Bank and Gaza. It calls to expel “Israel’s enemies” (which should be read as Palestinians) “back to their countries of origin.” At the same time, the party wants to encourage diaspora Jews to emigrate to Israel, in order to try and prevent assimilation.

As far as security policy, the party wants “deterrence” to be restored to the Israeli army, and for the military to move from “a policy of ‘containing the enemy’ to one of elimination and annihilation.” They want to encourage procreation and fight abortion. They envision a “Jewish democracy” that “rejects universal values.” And they name their economic policy “Jewish capitalism” — part of which proposes that once “Israel’s enemies” have been expelled from the country, the security budget will be reduced by billions of shekels that can be partially reinvested in industry, small businesses and the periphery.

Total war, expulsions, annihilation, mandatory Orthodox religious law, pro-natalism, ethnic supremacism — those were Kahane’s calling cards, and they are Jewish Power’s, too. Thirty years ago, those policy proposals saw Kach outlawed. Today, they have led to an invitation from the prime minister, delivered via Jewish Home, to join his coalition. So what happened?

It didn’t start with Kahane

It would be easy — and for many, a cold comfort — to point to men like Kahane, Netanyahu, and the Jewish Power crowd as aberrations in Israel’s politics. Yet to take this stance is to suggest that Kahane’s ideas, and Netanyahu’s policies, are without precedent in Israel’s history. And when we take an honest look at the last 70 years, can we really say they are?

Expulsion was on the lips of Israel’s first prime minister, and was instrumental to the founding of the state. Intermarriage has never been possible in Israel, albeit without the threat of incarceration (a Conservative rabbi was briefly detained last year for officiating non-Orthodox weddings). Campaigns for a Greater Israel, backed by public figures from across the political spectrum, have been around since the occupation commenced, and even before. Legal status aside, Israel has been in the process of de facto annexing the West Bank for years, through a combination of demolitions, evictions, land expropriations, settlement-building, and “transfer” plans. Every discussion of the “demographic threat” that accompanies supposedly progressive two-state proposals invokes the specter of ethnic segregation.

For the past 20 years Israeli society has been shifting inexorably to the right, with the process accelerating since Netanyahu was elected in 2009. But neither Kahane nor Netanyahu is solely responsible for brutalizing Israeli society. The roots of what we are witnessing go back much further, and to something much more fundamental about the state. The fact is that Israel has not, for a single day since its founding, been a state for all its citizens. And in this lies the raw material for the havoc that we see today.

Indeed, the real impact of this latest political development is that it has once again blown apart the “bad apples” defense that is applied to everything from settler violence to the occupation itself. Indeed, progressive defenders of the “Jewish and democratic” balance tend to exceptionalize acts of state and social oppression against Palestinians, arguing they are signs of a political system wheezing under the strain of a 50-year military occupation and malfunctioning dangerously, perhaps beyond repair. But such protestations have long rung hollow, in much the same way that the cries of “this is not us!” did following Trump’s election in the U.S. — as if white supremacy had never darkened the country’s door. And as if racist state and interpersonal violence was a novelty in Israel’s history.

These arguments long predate the current political moment and will, it seems, long outlive it. In the immediate term, however, Netanyahu’s decision to extend the hand of power to unabashed purveyors of Israeli fascism offers us both a particular and a universal lesson: firstly, that in trying to square the circle of a “Jewish and democratic state,” the latter always has, and always will, play second fiddle to the former; and secondly, that a purported democratic system which offers the trappings of true democracy to the hegemonic group alone can, even when it is functioning as intended, bring fascism into power. Israel is by no means alone in that regard.

It is, then, somewhat ironic that Rafi Peretz, the new head of the Jewish Home party, on Wednesday defended the Jewish Power merger by stating: “When the house is burning…I don’t look too closely at whoever will help me put out the fire.” He is right about the state of emergency — but wrong about who’s holding the matches.

Information on Meir Kahane’s policies and proposals, for both the Jewish Defense League and Kach, are taken from the following books: “The False Prophet: Rabbi Meir Kahane,” by Robert I. Friedman (1990); “Heil Kahane,” by Yair Kotler (1986); “The Story of the Jewish Defense League,” by Meir Kahane (1975); and “Never Again! A Program for Survival,” by Meir Kahane (1972).