As much as it chagrins the likes of Elliott Abrams, the increasing difficulty they are having with defending Israel’s policies is due to the policies they are working to defend. The longer the occupation continues, the less support it will find among Jews in the United States.

By Mitchell Plitnick

Over the past few years, there has been a good deal of consternation in Israel and in the American Jewish community about the relationship between the two. That concern has grown as Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu consistently works to please his right flank with ever more controversial statements and actions amid a petrified peace process.

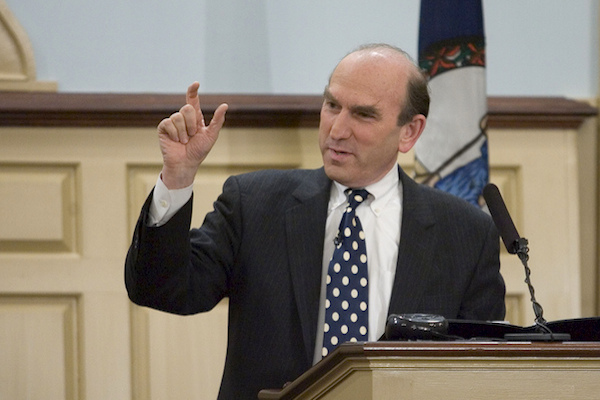

Neoconservative pundit Elliott Abrams reviewed two new books that document this phenomenon and try to explain it. Trouble in the Tribe: The American Jewish Conflict over Israel by Dov Waxman of Northeastern University and The Star and the Stripes: A History of the Foreign Policies of American Jews by Michael Barnett of George Washington University both look at shifts in Israeli policy over the years and examine the effects of those policy shifts on Jews in the United States. Abrams sees both books as blaming Israel for the growing divide with the U.S. Jewish community, and he feels compelled to respond by laying the blame instead on Jews in the United States.

Waxman’s book focuses on the divided reaction of Jews in the United States to Israel’s nearly 50-year old occupation and the Netanyahu government’s policies that entrench and maintain it. Barnett examines the tension between the more tribalistic and nationalistic Israeli Jewish society and the liberal, cosmopolitan U.S. one. In both cases, the authors make the case that the differences between the Israeli and American Jewish communities are driving a wedge between them and pushing Jews in the United States farther away from Israel, politically and communally.

Channeling Kristol

Abrams’ review carries loud echoes of the neoconservative icon, Irving Kristol. Like Kristol, Abrams believes strongly that Israel and the Diaspora Jewish communities are inextricably linked and that Jewish survival in the long term depends on those Diaspora communities, especially in the United States, supporting Israel absolutely. Kristol did not believe that Diaspora Jews had to back all of Israel’s policies blindly. Indeed, most of Kristol’s work was written at a time when Israeli political discourse was far more liberal than it is today. He believed, therefore, that it was “tremendously important to translate the classics of Western political conservatism into Hebrew,” so that Israelis could benefit from the “genuine political wisdom” of the West.

It was important to Kristol, and still is to Abrams, to root out the liberal and universalist trends that had become the hallmarks of the American Jewish community (and were once, particularly in the 1990s, rapidly growing trends in Israel). These trends, both men correctly understood, are completely at odds with the sort of narrow, tribalistic, self-interested, and nationalistic politics that they believed to be the only political path to long-term Jewish security, in Israel as well as the Diaspora. As a result, Abrams is ideologically committed to opposing the very values that Waxman and Barnett contend are causing discomfort with Israel for Jews in the United States.

Abrams begins by dismissing Waxman’s contention that “American Jews … have ‘greater knowledge’ about Israel today than did their parents or grandparents.” He sarcastically asks, “Why would that be, and where did they acquire their balanced and penetrating insights—by reading the New York Times?” The comment implies a casual dismissal of the massive difference between the information that people around the world have access to today than in the past.

To begin with, for the past 25 years or so, people all over the world have had easy access to historical research that, even if one only reads Israeli, Jewish, and Zionist authors, tells a much more nuanced story of Israel’s history than was commonly available previously. Israeli writers such as Benny Morris, Avi Shlaim, Tom Segev, and others caused a stir with their books in the 1980s and 1990s. More than that, they forced less controversial historians to broaden their own scopes in order to be academically credible. That discursive context was established just before the Internet age permanently altered the accessibility of news and analysis everywhere.

Clearly, The New York Times, whatever its value, is far from the only source of information people have about Israel and its occupation of the Palestinian people. Israeli news sources, as well as European, Arab, and other global sources, provide a far fuller picture of life for Palestinians, as well as the effects of nearly 50 years of occupation have had on Israel. In the past, Israeli peace and human rights groups, to the extent they existed, rarely tried to disseminate their materials in the United States and often did not even bother translating them to English. Now, human rights and other progressive groups in Israel, the Palestinian Territories, and around the world report on conditions under Israeli occupation as well as the increasing ethnic tensions within Israel itself.

The advent of video on social media has also served to open the eyes of many to the inevitable nature of any military occupation, especially one that has gone on for so long. Surely, Abrams is well aware of all of this. But he inexplicably, and without substantiation, dismisses the notion that people today are better informed about Israel than they were in the past.

The views of liberal Jews

The thrust of Abrams’ point is that more assimilated and intermarried Jews, as Jews in the U.S. increasingly are, cannot have the required passionate attachment to Israel that will lead them to support it. Jews in Canada, the United Kingdom, and Australia, he says, “tend to cast their votes for the political party that supports Israel, having switched allegiance in recent decades to help elect Australia’s Liberal party as well as leaders like Margaret Thatcher in the UK and Stephen Harper in Canada.” By contrast, Jews in the United States vote for more progressive candidates, prioritizing domestic issues over Israel.

In other words, for Abrams, the problem is that Jews in the United States do not vote based on their connection to Israel but rather based on domestic concerns. Although true, it doesn’t follow that this means that Israel is not very important to Jews. The widespread political engagement on the issue is an obvious marker of Jewish attachment to the issue of Israel, but the numbers also don’t support Abrams’ view.

The few data points Abrams uses are not conclusive. In the recent election in Canada, for example, the Conservatives did not win a majority of the Jewish vote, as they had in 2011, despite Prime Minister Harper’s clear dedication to supporting Israeli policies. And, aside from the United States, the Jewish community outside of Israel is small and not particularly influential. Their size makes them more vulnerable to anti-Semitism, an issue which has been much more in the forefront in places like England and France. They also tend to be relatively affluent, which many observers note is at least as big a factor in the community’s shift toward more conservative voting.

And if Abrams is correct, how can he explain the rise of Jewish groups critical of Israel’s policies like J Street and Jewish Voice for Peace (JVP)? To be sure, some Jewish groups of the past, such as New Jewish Agenda and Breira, have always objected to Israeli policies. But the widespread appeal, political influence, and sheer size of J Street and JVP are unprecedented.

Even staunchly pro-Israel groups like the American Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC) are boasting much greater numbers at their annual conferences and a larger membership than they have in the past. It’s impossible to reconcile this level of engagement with Abrams’ statement that, “The American Jewish community is more distant from Israel than in past generations because it is changing, is in significant ways growing weaker, and is less inclined and indeed less able to feel and express solidarity with other Jews here and abroad.” Abrams is, of course, correct in saying that Jews in the United States are less connected to synagogues and Jewish communities in general than in the past. But are they less connected to Israel? A 2013 Pew poll found that 69 percent of American Jews were “very attached” or “somewhat attached” to Israel. That’s the same number as in a 2000-2001 poll that Pew conducted.

Moreover, Abrams bemoans the fact that “only about 40 percent of American Jews have bothered to visit (Israel) at all.” He might be surprised to learn that, according to a 1994 paper (presumably a time before U.S. Jews “abandoned” Israel in Abrams’ view, or at least before the problem was as pronounced as he would see it today) less than 30 percent of American Jews aged 26-64 had ever visited Israel. And, given the fact that tourism to Israel gradually rose from 1948-1995, when it experienced a huge leap, Jews were certainly not visiting Israel, a country that costs a great deal of money to visit, more frequently in the past.

So, although more Jews are intermarrying and disassociating themselves from the mainstream Jewish community in the United States, engagement with Israel has demonstrably not declined. In fact, a 2010 study from the Cohen Center for Modern Jewish Studies at Brandeis University showed a slow and gradual rise in the attachment of American Jews to Israel since 1986.

The salience of Israeli policies

What has changed is the nature of that engagement. Politically conservative Jews may be able to find common cause with an increasingly right-wing Israel. But the vast and liberal majority of American Jews, faced with the realities of Israel holding millions of people under military occupation for five decades and of the increasing and increasingly violent hatred of Arabs and fellow progressive Jews in Israel, have been forced to choose between supporting an Israel that doesn’t reflect their universalist values or speaking out in favor of those values.

Jews in the United States, like Jews everywhere, overwhelmingly support Israel’s existence. But many cannot ignore an Israel that has repeatedly killed and injured many civilians in Gaza, intentionally or otherwise, destroying the infrastructure there and causing massive poverty and misery. They can’t ignore the settlement expansion that cannot be reconciled with a two-state solution. They can’t ignore an Israeli government that brings out voters with racist scare tactics and that includes prominent figures who support annexing major parts of the West Bank. And they certainly can’t ignore an Israeli prime minister who blatantly interferes in U.S. politics in order to block an international agreement that Israel’s military leaders, and many others, uniformly agree would, and has, scored a huge victory in pushing back Iran’s potential for acquiring a nuclear weapon.

As much as it chagrins Abrams and other neoconservatives, the increasing difficulty they are having with defending Israel’s policies is due to the policies they are working to defend. The longer the occupation continues, the less support it will find among Jews in the United States.

That is not due to Abrams being wrong about the source of that reality. He’s actually quite correct. Occupation, the siege of Gaza, and the increasing violence against Israel’s Palestinian citizens are thoroughly incompatible with universalist, liberal values. A more tribal, nationalistic political outlook can accept or at the very least tolerate such things.

Indeed, what’s truly remarkable is how many otherwise liberal Jews have been, and still are, able to excuse the occupation. But until now, Jews who opposed the occupation had no voice. Now, with J Street on one end of the anti-occupation spectrum and Jewish Voice for Peace on the other, and a good number of groups in between, Jews who believe that Palestinians must have the same basic rights as Israelis have a voice. And, yes, this is an outgrowth of the long-held acceptance of universalist, liberal values among Jews. That trend shows no sign of slowing, much less being reversed. As a result, we can all, left and right, look forward to growing Jewish opposition to the occupation.

Mitchell Plitnick is the vice president of the Foundation for Middle East Peace. Follow him on Twitter at @MJPlitnick. This article was first published on LobeLog. It is reproduced here with permission.