The immediate trigger to start building the wall was the security of Israeli citizens. Ten years later, with all the known accumulated effects on Palestinians, nature, economy and political affairs – has the barrier fulfilled its stated goal for Israelis?

Project photography: Oren Ziv / Activestills

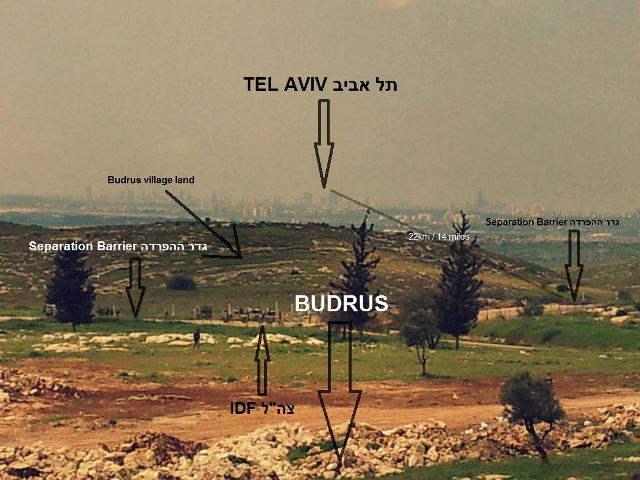

Standing on the cemetery mount in Budrus, at first sight the separation fence seems to make perfect sense. Over the clouds of tear gas rising from the field below where the village youth and the army youth are exchanging stones for grenades, beyond the fence which is now almost on the Green Line after the famed local popular struggle led the army to change the route of the fence and give back 95 percent of the village’s lands, and through the brownish fog of car smoke that sits on top of the heart of the land – one can clearly see the Tel Aviv skyline. Only twenty kilometers away, one can actually recognize some famous buildings that seem surprisingly close.

Standing here, one can easily understand why Israel wants this fence to be here. As mentioned in the first chapter of this series, it was the wave of suicide attacks on Israeli cities that created public pressure on the government to build the wall, and this fence here that prevents Palestinians from accessing the biggest metropolis in the country freely and quickly seems to be just the solution.

Yet a second glance is also needed here. Taking one’s eyes away from the city’s skyline, one can also see the demonstration dispersing, the gate in the fence opening, the army jeeps storming in, the cannon installed on one of them shooting some 20 tear gas canisters into the village, the soldiers attempting to make arrests and the families trying to seal their doors and windows in face of the gas.

This second glance can also be a reminder that some 100 dunams of land are still caught on the other side of the fence, that the army (like any Israeli) can still freely enter this place and do as it pleases, that had it not been for the struggle the fence was due to annex twenty times more land, costing farmers their livelihoods, and that in most places there was no such struggle, or no such success in it. It also reminds one that the current state of affairs is still unacceptable to the millions living under military regime, and that they will go on fighting it one way or another until independence. This makes things a little more complicated.

“There is no doubt that the route endangers troops”

“Ask the average Israeli what he thinks of the wall and he’ll say ‘look, I’m saving my skin here, so hell yeah – let them stand the extra two hours in a checkpoint, because he’d think the question is whether to build a wall or not,” says Colonel (res.) Shaul Arieli, a member of the Council for Peace and Security and co-author of The Wall of Folly (“Khoma U’Mekhdal”). “In such a case I think he’d be totally right, because life always supersedes anything else. But that’s just the bluff – as there is no real argument on the question of whether Israel has the right to build a wall. The entire world says we can use a fence, a wall, a river filled with alligators, just as long as it’s on the Green Line. This is where Israel is in disagreement, and where the government willingly chose to endanger its citizens for the benefit of other interests, such as settlements.”

As mentioned earlier in the series, the length of the zig-zagging barrier is more than twice that of the Green Line and is thus clearly harder to protect. But it’s not just the route as a whole that offers less than the best defense possible, it’s also certain specific fragments of it. In 2005 the High Court of Justice repealed its own ruling, and shifted the fence built near the settlement of Tzufin. Justice Aharon Barak ruled that the state lied to the court by hiding the fact that this section of the route was planned for the benefit of future settlement expansion – and not solely for security reasons. It was a ruling that would cost the fence planner and the settler Colonel (res.) Danny Tirza his job – but not to worry: the same Tirza has recently been hired by Prime Minister Netanyahu to sketch a future border for Israel to present in negotiations.

In a different case, that of the village of Bil’in, the court found that not only was the route planned with the expansion of the Matityahu East settlement in mind, but that it was actually tactically inferior. “There is no doubt that the route endangers patrolling troops,” wrote former Supreme Court President Dorit Beinisch. “Considering previous cases in which we were told of the importance of keeping the fence in dominant topographical positions the current route raises some questions.”

While it is possible to argue that cases such as these prove the security value of the wall, as the system appears to be able to mend its own errors where the route requires it, I wish to add some skepticism to the equation: for who is to say that the local Palestinian community even bothered going to court in all places where planners chose an annexing route? Who’s to say that evidence such as that hidden by the army and revealed by the petitioners in the cases of Jayous and Bil’in could have been revealed elsewhere? And what about the long term security implications of the High Court’s own consistent choice to accept the state’s odd claim that the wall is “temporary” and may thus be allowed to engulf and protect major settlements?

The Palestinian choice

Even if we choose to ignore the long and winding route or the instances in which wall planners lied about their true motives – we cannot ignore the security implications of four parts of the wall not yet being built. In three of these (Adomim Plains, Gush Etzion and the Judean Desert) construction is not even planned to resume anytime soon, and even in the fourth – southwest of of Jerusalem– one can still see the capital’s skyline from neighboring Palestinian villages and unlike in Budrus, one can simply cross over.

“These gaps allow infiltrators, drugs and weapons to pour in, as well as murderers,” says Arieli. “Yet they are not sealed off only because the government wants to annex large chunks of land and it knows the court would not allow it – so it forfeits our security.” “There’s no problem crossing the gaps in the fence and tens of thousands of illegal workers cross it back and forth every day, and there should be no problem getting suicide bombers through with them” stresses Ilan Tsi’on, co-founder of “A Fence for Life.” “So why don’t they? Because that’s the Palestinians’ choice. They know that if the fence is complete they will be faced with more facts on the ground, and will take away their option of influencing us. So in fact, our security is really an illusion.”

Arieli and Tsi’on’s answers highlight a new attitude to the security question: While the number of suicide attacks in Israeli cities has dropped significantly since construction of the wall began and while the wall did have its effect on this goal, it was not the only cause. Brutal oppression of the Second Intifada, reoccupation of Palestinian cities, mass arrests, pressure applied on civilian populations, and the work of the General Security Service all had their effects – as did the Palestinians’ choice to turn to a course of unarmed popular resistance, of encouraging economic, academic and cultural boycott, and of diplomatic work on the international level. “Yes, we have a barrier with armed patrols and that gives something to security, but does it bring calm? Of course not,” says Arieli. “The proof of that is that would-be terrorists are not captured around the wall as they used to be in Gaza before we started shooting anything that comes close to the wall there. If nobody is captured – it means that the wall itself is not what’s stopping people.”

The wrong question

IDF commander of the Paratroopers Brigade, Col. Amir Baram, recently told Ha’aretz that “Before the fence there was no efficient defense. The General Security Services (GSS) would warn that a suicide bomber was on the way, and I knew there wasn’t much we could do other than place soldiers on the road and hope for the best.” Yet even this combatant knows that the barrier cannot be a solution in the long run. A fence can be cut, a wall climbed over, and of course missiles can fly above anything. As Ilana Hammerman recently wrote in an op-ed, “no historic circumstance has been invented in which such a-symmetry (between occupier and occupied) would guarantee a life of calm and security.” These words were echoed in Sheerin Al-Araj’s grim prophecy earlier in the series in which she said: “It might take 10 or 15 years, but things will change, and when they do Israel will most likely not only have to deal with Palestinians but with the entire Arab world. I really hope Israelis understand this now and find a solution that won’t lead us to killing each other.”

Most countries in the world, the ICJ, the Palestinian leadership and most the activists struggling against the wall in their villages and cities (aside from supporters of the one-state solution) would agree to Israel’s building a security wall on its recognized border, the Green Line. Yet as long as 85 percent of it is built beyond that on Palestinian land, as long as it is transparent to Israelis, as long as it harms farmers and workers the way it does, and as long as the occupation continues – no solution and no barrier can truly offer Israelis security.

The question, therefore, is not whether or not a wall, any wall, offers security (which it probably does to some extent) – but rather whether this specific wall with this specific route offers true and lasting security more than other existing alternatives. The answer to that is almost certainly: No.

(As mentioned in previous chapters, despite my repeated requests, the Ministry of Defense refused to grant an interview with any official regarding the planning or construction of the wall for this series.)

Previous chapters in this series:

Part 1: The great Israeli project

Part 2: Wall and Peace

Part 3: An acre here and an acre there

Part 4: Trapped on the wrong side

Part 5: A new way of resistance

Part 6: What has the struggle achieved?

Part 7: A village turned prison

Part 8: A working class under siege

Part 9: Dividing land – water, fauna, flora

Part 10: My encounters with the wall in space

Next and final chapter:

Part 12: Where do we go from here?