Between the years 1948 and 1952, thousands of Yemenite babies, children of immigrants to the newly-founded State of Israel were allegedly taken away from their parents and given up for adoption to Ashkenazi families. Now, poet and activist Shlomi Hatuka goes back and speaks to the adoptees about one of the most painful, covered-up stories in the history of the state.

By Shlomi Hatuka (translated by Miriam Erez)

Dedicated to my grandmother, who gave birth to twins in a hospital, and came home with only one of them. May her memory be a blessing.

In Tsipi Talmor’s documentary film, Down a One-Way Road, we see Sarah Pearl, the former head nurse of the Women’s International Zionist Organization (WIZO), stating the following: “They were constantly bringing [us sick] children…as soon as they recovered, they were taken away…we were always at 100% occupancy. [Biological] parents never came. But donors did.” Pearl states that when she asked the head administrator why parents never came to visit their children, she received the following answer: “[The parents] have lots of kids, and lots of problems. So they don’t want their children.”

1.

Hanna Gibori, a social welfare worker from 1948 to 1954, and head of adoption services in the Northern District, testified before the state investigative committee that submitted its conclusions in 2001: “Hospital physicians handed over babies for adoption straight out of the hospital, without the official adoption agencies being involved.” Gibori added that if a baby was in her care, and no one showed any interest in it, it was placed with a family without being formally adopted. H. Leibowitz, then head of Adoption Services, described a Public Services Committee meeting in 1959:

“There is also de facto adoption, and it should also be considered. There are children who are in the care of the welfare system, and there are children who are placed by a third party, and there are children – and this is a tiny minority – who are placed by their birth parents.”

In a Knesset plenary that same year, MK Ben-Tzion Harel called a spade a spade: “A not-to-be-dismissed percentage of children are adopted straight from the hospital or maternity center. In some cases this is done in unacceptable ways, in a manner that borders on trafficking…”

Then there’s the April 21, 1950 letter from a Dr. Lichtig, head of hospital at the Health Ministry, to the state hospitals in Haifa, Pardes Katz, Tzrifìn, and Dajani (Tzahalon), titled “Returning sick children from the transit camps”:

“There are cases that have come to our attention of children who have been released from hospitals and not been returned to their parents’ custody. Apparently there are couples wishing to adopt who act quickly. Meanwhile, the bereft parents search for their children. [I’m sure you agree that] there is no need to explain that it is incumbent upon us to make every effort to prevent such incidents […] The camp administration shall [hereby] be responsible for children’s being returned to their parents, as it is also responsible for the children’s having been hospitalized…”

The act of adoption is supposed to rectify a painful hole in an individual’s life. Despite the fact that in most cases adoption is successful and the adoptee benefits from a loving family, it is also an is inherently tragic situation: every individual wants to know who their biological parents are. The adoption process takes this into account, and besides placing the adoption file – which should contain as much information as possible – at the adoptee’s disposal, adoptive parents also obtain information about their child’s birth and life up until their adoption, so that when s/he wants it, it is available.

And herein lies the great tragedy of the Yemenite, Middle Eastern, and Balkan “adoptees” (and the ensuing abyss in their lives): since the abductions could not have been carried out with the biological parents’ knowledge, the adoptees’ trails were so well-covered that their ties to their biological parents were wiped out, rendering them waifs – most making many interim undocumented stops along the way, others being taken from their parents immediately after birth or upon landing in Israel.

Southern District Head Physician Dr. Yosef Yisraeli says that there existed a policy of transferring hundreds of children from hospitals to group homes far from their parents’ residences, and then giving them up for adoption. Even the legal system did not refrain from being involved, lending a hand to the erasure of the children’s tracks. In the 1950s, there were no laws governing adoption in Israel, and lone voices cautioning against child trafficking and the urgent need for codifying and monitoring adoption were dismissed.

One of those voices belonged to High Court Justice Shneur Zalman Cheshin, who wrote in a May 1955 decision:

To our embarrassment, fictitious adoption orders and custodial orders are issued weekly, indeed daily, using methods of tenuous routes, bypassing and sneaking past the authorities, …dubious interpretations [of the law], convoluted arguments, and sleight of hand […] Even the rabbinate has begun issuing adoption orders.

But Cheshin’s earnest entreaties swam against the current, and in the late 1950s, a law was passed containing a terrifying clause according to which the parents of an adopted baby or child need not be present in court to give their agreement at the time of the adoption permit’s issuance, nor can they appeal the decision. And all this within the bounds of the law, not to speak of adoptions carried out outside the law, or under explicit trafficking conditions.

All this leads up to the fact that in none of the cases I will describe was adoption carried out as we now understand it. In the vast majority of the cases, the biological parents’ details (including the birth mother’s name, date and locale of the birth) do not appear. Furthermore, the reason for the child’s being put up for adoption is not stated, and in rare cases in which the biological parents’ details are recorded, their signatures are absent from the adoption document. In fact, in none of the cases described – not a single one – is the signature of a biological parent found confirming that s/he forfeits her rights as a parent; and there is no testimony of a signature ever being required for doing so in any legal framework.

2.

As if that were not enough, not only was the child’s trail covered up in many cases, but also their very adoption. In these cases, the adoptive parents acted as the main driver when they “…not only changed their child’s name, but her ID number, so that the event could never be traced,” according to Yehudit Hibner’s (a retired senior Interior Ministry employee) testimony before the state investigating committee. Her full testimony will remain classified until 2066.

Many adoptive parents went even further: private investigator and attorney Ofer Kochi, who personally investigated the matter and who found and made the following statements available, found that in 1954, Health Ministry Legal Advisor Eliezer Globus cautioned physicians against recording births retroactively. Kochi discovered that parents adopted children and claimed afterwards to have given birth to them, thus obtaining the requisite birth certificate. Globus:

Before us lies the question of retroactive recording of birth, as well as another disturbing question, that of recording of adoption in the birth registry. […] I’ve written countless times already that entries in our birth registries are [to be] as per the provisions of clause 4 of the Public Health Act of 1940; there is no other law. This clause refers to actual births, involving labor and umbilical cords, not of adoption and not of documentation of adoption. […] [Any other] notice of birth conveyed by the woman is false, invalid, and it is forbidden to use it.

This is only part of the directives that Globus wrote and were distributed by Dr. Yaffe to the hospitals and birthing centers under the directive “Recording of Births of Waifs Who Were Adopted.” It is a long directive characterized by genuine terror, written after it was discovered that instead of reporting adoptions, adoptive couples reported births that had not happened. In such cases, there is no adoption file to be found.

These cases differ from more recent practice, wherein the birth certificate is recorded under the adoptive mother’s name in order to conceal the identity of the birth mother from the adoptee. One of the most scandalous discoveries of the state investigative committee – a stash of birth and death certificates signed in advance – aroused fear that beyond the adoptive parents’ false declarations of birth were Interior Ministry clerks who colluded in issuing falsified birth records:

Two years earlier, in a 1952 article published in Haaretz (below), Mordechai Artzieli exposed the issue of adoptions stemming from huge demand. According to Artzieli: “One can understand the couples who go the black market route. It stems from the desire to cover all traces of the adoption so that the adoptee will never know.”

The article opens with the matter of skin color – an inextricable part of the entire phenomenon at that time: Ashkenazim sought to adopt children of light complexion, but were compelled to make do with dark-skinned children, as that was what was available. Artzieli says:

It’s not the first time that Mizrahi children have been adopted by Ashkenazim. One of the grave components of adoption in Israel is the ‘complexion problem’: while most of the couples seeking to adopt are Ashkenazi in origin, most of the children placed for adoption are Mizrahi…” [Obviously, in most of these cases, the adoptive parents could not hide the fact that they were adopted from their children, as reflected in the stories that I present. At the same time, there are adoptees who only found out that they were adopted by accident. S.H.]

The erasure of the tie between the biological parents and their children, in which many parties had a role, not only led to most of the adoptees ultimately seeking out their biological parents in vain, but also a decent number of them never even knowing that they were adopted. That is the first answer to the question asked by journalist and television personality Yaron London: Where did the adoptees disappear to? Perhaps they didn’t “just disappear”? [Hebrew] As incredible is it sounds to us, this is the reality of dozens, if not hundreds, of Israelis.

Where indeed? The very act of asking is in fact ignorance incarnate, even if one is an autodidact. As one can glean from the quotes and stories that follow, no one is disputing the existence of illegal or secret adoptions that took place in large numbers during those years; it could not escape one’s attention and was in fact a conspicuous, society-wide phenomenon then as is its exposure today. And yet, it is one of the most covered up and repressed phenomena in Israel’s history. From 1948 to the end of the 1950s, there were 6,000 adoptions, with some estimates placing the number over 10,000. Although a minority of adoptions were legitimate, the phenomenon was so widespread that it led Judge Cheshin to write a book about it [Hebrew].

3.

The other answer to “Where did they go?” lies in the relationship between the adoptees and their adoptive parents. Of all of the adoptees that I met and interviewed, not a single one turned their back on their adoptive family. Their adoptive family is their rock, their home and their space, both physical and emotional; it is the strongest psychological component of an individual. They view their adoptive parents as mother and father in every respect, in most cases having enveloped them in love and having given them everything they could. The need to protect them manifests to the point that some adoptees hide the fact that they discovered that they are not their biological children, or that they found their biological parents – a rarity in both cases. More than a few even chose not to find out about their backgrounds in order not to open old wounds, either their parents’, their own, or both.

Note the recent verdict handed down by Judge Nili Maimon in the case of an adoptee who, together with his adoptive family, sued his biological family after the latter contacted him against his wishes:

It is the adoptee’s right not to know who gave birth to him…He has a right to avoid psychological pain, possibly unbearable, [caused by] questions, wondering, awkwardness, and mental and emotional confusion entailed in finding his biological parents and family.

Judge Maimon ordered the defendant to pay the plaintiff NIS 400,000. The unequivocal favoring of the good of the child over the wishes of the biological parents inherent in the 2013 verdict is a consequence of those regulations and laws passed in the 1950s, the effect of which has not dissipated since.

More recently, organizations [Hebrew] have been established, both by biological parents and adoptees, which vehemently oppose both the imperviousness of the agencies that manage adoption and the laws regulating them, as well as the option of opening the adoption retroactively to the biological parents. The organizations also advocate for the right of adoptees to open their files and obtain information on their biological families. There is no doubt that the Yemenite children affair has cast a shadow over our legal system to this day: the erasure of the tie between biological parents and adoptees has in fact become the elephant in the room.

Many who have investigated the affair have encountered adoptees who refuse to come forward, or refuse to open their files for the aforementioned reasons. Yet, along with the quite natural anxiety and the understandable desire not to turn their worlds upside down (not to mention those of their biological parents), exists the terrifying cloud hovering over their adoption: the abduction of Yemenite children.

As previously mentioned, some of the adoptive parents took an active role in covering the tracks that would have led to the biological parents. At the same time, however, at least some of them shudder to discover after all these years that the child they so desperately sought to adopt (in most cases their only child) reached them via illicit means – without the biological parents’ knowledge nor agreement, in most cases after the latter were told that their child had died.

It is a heavy cross for the adoptees and their adoptive parents to bear. And if that is not enough, there are no details of the abduction itself; basing the story on the parents’ testimonies has in many cases led to the adoptees reaching the errant conclusion that they were abandoned. The anger and disappointment leads them to want nothing to do with their biological parents.

No one denies the transfer of hundreds of children in both WIZO and Agudat Yisrael [non-Hasidic ultra-Orthodox social welfare] institutions. Investigative committee documents, as well as documentation by private investigators, are filled with testimonies by nurses and caregivers who describe the “underground adoption railroad” in the 1950s – a large portion of which were headed abroad, in blatant contravention of the British Mandatory Law that the Knesset adopted (the testimonies are classified. See below).

4.

The following are the stories of the adoptees, some of whom I met and talked with. Most were taken from newspaper articles, or obtained with the help of other researchers. The incredible story of Shoshana and her twin brother is published here for the first time. As I have mentioned before, in none of these cases – not a single one – can the signature of the biological parents relinquishing their rights, be found. Furthermore, there exists no evidence that they were legally required to do so.

* * * * * *

Yehuda Cantor, of Yemenite origin, was born in the 1950s and discovered that he was adopted when he was 24. His adoptive parents had kept his adoption a secret, and he confronted them upon discovering the truth. When he opened his adoption file, he found it to be empty, save for a single page that stated: “The mother gave up her son for adoption.” Cantor was not allowed to receive a copy of the documents or even photocopy them, and was forced to copy them by hand. His biological mother does not exist; her signature is missing.

Cantor does not posses a birth certificate, and his adoptive parents’ document of registration contain only sketchy details that lead nowhere. Despite his wishes, Cantor could not locate his biological family, and at one point was refused the results of a genetic compatibility test. His DNA signature is locked away in a European lab, and anyone wishing to check compatibility is welcome to do so.

Yigal Mashiach, then writing for Haaretz, was one of the first to report on the incredible difficulties the adoptees have in coming forward with their stories. In 1955, Mashiach first published Cantor’s story as part of an investigative series. A week earlier, he published the story of Miriam Shoker and Tova Barakha, both of Yemenite descent.

Adina, now Miriam Shoker, has known that she was adopted since she was 12. However, she did not know that her biological father had been looking for her since the day of her disappearance. On the contrary, she believed that her parents had abandoned her, which is why she never opened her adoption file.

But her biological father never gave up. He searched unremittingly for years and even filed a complaint with the Shalgi Commission. Atypically, the commission found her, but never bothered to inform him. An attorney he hired discovered this while looking through the commission’s archives.

For eight years, Shoker hid the fact that her biological family had found her from her adoptive mother, only revealing her secret when she realized that her decision was wrong and felt that she owed it to other adoptees to come forward.

I grew up with a lot of anger at my biological mother, whom I believed had abandoned me. I never understood how and why this could be possible. My adoptive mother revealed the secret of my adoption to me when I was 12. Imagine: A girl grows up ‘knowing’ that her mother had abandoned her. Imagine what it does to her mentally and to her development. Only after I found my biological mother did I realize this was not the truth: there was no neglect or abandonment in this story. This was a story of deceit. This is why I recommend that all adopted children come forward and look for their biological families. So that you don’t cultivate ill-placed anger. After all, most of these children were not abandoned. (Mashiach, ’95)

Unlike Shoker, most of the adoptees weren’t fortunate enough to meet their biological parents and correct their assumptions. Note that Shoker’s adoptive mother told her repeatedly that her adoption was legal, as did the official committee that located her. It was recorded that Shoker was adopted legally. Still, her adoptive mother said that she took her directly from a children’s home in Rosh Ha’Ayin, and that when she heard that Miriam’s biological father was searching for her, she ignored it.

At 12, Tova Barakha found out from one of her aunts that she was adopted.

She [my adoptive mother] told me she couldn’t have children and that she and Dad went to WIZO to ask to adopt… [there] they were taken into a large room and told, ‘Pick out whoever you want and take them’. Mom says it was like a marketplace. Many, many crying children. Dad wandered around for a long time and finally picked me. They took me and left. (Mashiach ’95)

Years later, Barakha tried to open her adoption file, but the social services clerk would not let her see it. Finally the clerk agreed to tell her only that her biological mother had emigrated from Yemen alone, and that her name prior to the adoption was Leah Sa’adia. Barakha has chosen to tell her story in order to encourage others to do so – to dispel doubts. She, however, has despaired from finding her biological family.

Two other women of Yemenite origin – Ziona Heiman and Tzila Levine – also chose to come forward: their adoption files were found to be empty, and both had to search for their biological families either through the media or by relying solely on physical resemblance. Levine’s story, which has had a great impact, was published by Oron Meiri and Smadar Partosh in Yedioth Aharonot in 1997, as well as in Ma’ariv by Kobi Bleich. Heiman’s story was published by Yehudit Yehezkely in Yedioth Ahronoth in 2002.

Levine’s adoptive parents found her through a physician in Haifa. Relatives claim that they would not have adopted her had they known that she was abducted. However, Levine says, “When I asked about my past on the kibbutz, I was warned that it would be a waste of time and that I should focus on my current family. I realized that things were hidden from me and lived with a terrible sense of being part of a conspiracy”.

Levine’s adoption order was issued by Judge Moshe Landau, then a district court judge and later a High Court justice:

After considering an adoption request filed by Anda and Mordechai Rosenstock made on November 18, 1948 for the adoption of a girl, to be named Tzila Rosenstock, and whereas the girl is a waif and her parents are unknown, and whereas the girl was given to the applicants by the Hebrew Community’s committee, I hereby order that the applicants become the adoptive parents of Tzila Rosenstock.

And with that, one of Israel’s most respected judges signed off on and was complicit in a criminal act. In his defense, Judge Landau claimed that he dealt with many adoption cases and could not recall a specific one.

Based on the amazing physical resemblance between them, Tzila Levine and Margalit Omeissy took a DNA test that showed that they were indeed mother and daughter. The results caused a scandal that undermined the professional status of the Hebrew University genetics researcher who performed it, Dr. Hassan Hatib, who was thereupon the target of racist remarks from Prof. Yossi Hirshberg, who claimed that Hatib was only an animal genetics expert. Later, Hatib said that he was subjected to enormous pressure to negate his initial results and finally signed off on the test results, which he had neither performed nor believed, which showed the opposite results. Today he owns his own laboratory.

Despite her olive complexion, Tziona Heiman only discovered that she had been adopted after a classmate let it slip. When she demanded that her parents tell her the truth, they admitted that they had found her in a hospital, and that Yigal Alon, who then served as commander of the Palmach [the elite pre-state strike force that served as the precursor of the IDF] and was a senior figure in the Labor Party, had arranged her adoption. Ultimately it was Alon who brought her to her parents “as a birthday present.” Ruth Alon, Yigal Alon’s wife, recalls:

This couple asked us to help them adopt a child. We went to a Jerusalem hospital with them [where we found Tziona]. She was so sweet, a wonderful baby. We brought her to the kibbutz, but we had no way of knowing who her biological parents were.

When Heiman asked to see her adoption file, she was turned down by social services – a common response to such requests, along with delays that often last years – and was finally told that her biological parents’ names were Avraham and Sa’ida, and that she’d been given the middle name Ora. Thereafter, Heiman received several inquiries, and as far as she knows, has found her biological family.

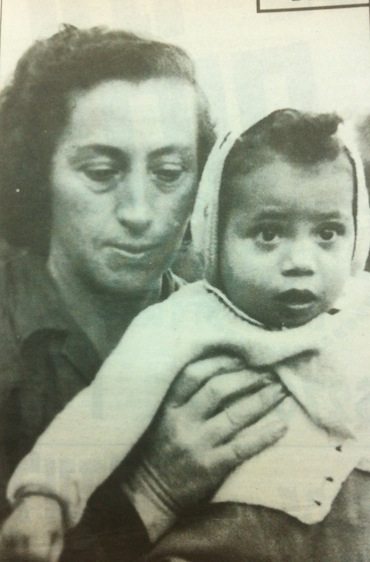

![Tziona Heiman and her biological mother. The state claimed that there is no biological tie and hid the [DNA] tests, and the family would not agree to further testing. “Judge for yourself” [right: Tziona Heiman as a child] [Caption] Tziona Heiman and her biological mother. The state claimed that there is no biological tie and hid the [DNA] tests, and the family would not agree to further testing. “Judge for yourself” [right: Tziona Heiman as a child]](https://static.972mag.com/dev/uploads//2014/01/haiman.jpg)

According to documents in his possession, in 1953 [Becher] was placed in the care of WIZO, and was thereafter adopted by Haim and Pini Becher, an immigrant couple from Turkey. He has a birth certificate issued in 1956 with his new name and adoptive parents’ names. He never received his original birth certificate.

Becher grew up in Haifa, and his parents never told him that he was adopted until, it being obvious to him that he was Yemenite in appearance, he insisted upon an explanation for the lack of resemblance. Though his parents told him that his biological parents had died, when he inquired, it emerged that he had been in WIZO’s care for two years, during which his biological parents were alive. Among other things, he discovered that his mother had given birth to him outside of marriage. All this was told to him orally; Becher was not allowed to even see his file. Despite an intensive search, the information provided to him led nowhere. At the end of his effort, Becher received the following letter: “All efforts made [to locate your biological parents] have been in vain. We have no clue as to your mother’s identity or whereabouts.”

Varda Fox discovered that she was adopted later in life, after which she discovered her Yemenite background. Her parents, an immigrant couple from Germany, told her that they had paid $5,000, (which amounts to $48,578 today) to adopt her. An Israeli social activist in Eastern Europe told me that today, the sums couples pay to adopt can reach up to $150,000. Although Varda told her story (published in Yedioth Ahronoth in 1993) in the Knesset plenum, as far as I know, she has never found her biological family.

Uri Wachtel, also of Yemenite ancestry, discovered that he was adopted when he was six years old.

Like scores of others, Wachtel was the only child of Holocaust survivors who could not bear children, and who grew up as the second generation of Holocaust survivors. When he asked about his adoption, his mother told him that she and his father adopted him from WIZO, where they were told, “Go ahead. Choose one. Like in an animal shelter.” Wachtel’s biological mother was compelled to put her children up for adoption at the Jerusalem WIZO after her husband died. One child was one-and-a-half, while the other – Wachtel – was five months old. She traveled daily from Atlit to nurse him, until she was told that both her sons had died in a flood. His brother Haim was found in a group home in Bnei Brak four years after his “death” and disappearance from WIZO. Genetic testing confirmed the relationship.

Vered Fox, who appeared in Down a One-Way Road, says that her adoption could not be concealed; as she put it, she was the “black daughter of white parents.” Yet she never opened her adoption file so as not to hurt her parents, since such an act could be interpreted as “…betraying them, as if their roles as mother and father [could be] erased. I just couldn’t do that to them.”

Despite the fact that the vast majority of abductees (80%) are Yemenite in origin, a significant portion are of other backgrounds; with admirable sensitivity, Rabbi Uzi Meshulem calls the whole affair “the [lost] Yemenite, Mizrahi, and Balkan Children”.

Some other examples: Tzvi Amiri Nee Biton, was born to an immigrant couple from Tunisia who lived in a transit camp in northern Israel. When his mother went back to Haifa’s Rambam Hospital, where he had been born prematurely and remained for further care, she was told that he had died. In fact, he’d been placed in foster care, and from there was adopted by a couple residing on a HaShomer HaTzair (socialist-Zionist) kibbutz, where his parents hid his adoption from him for years. When he ultimately found his biological family, he discovered that they had undergone tragedy after tragedy, all beginning with his disappearance. Their case is described by attorney Rami Tzubari in his book Looking for My Lost Siblings.

The name of a former Knesset Member is also tied up in the affair. In order to protect his privacy, I’ll not mention him by name, even though his part has been published openly in the press. He was born in the 1950s and grew up on a kibbutz. An immigrant couple from Kurdistan, whose children disappeared without a trace, claimed that they’d discovered that he was their biological son, and based on the resemblance, asked to meet with him and undergo DNA testing. The MK denied that he was adopted, while his adoptive mother claimed that she’d given birth to him. At the same time, growing doubts arose surrounding their claims, which ultimately led to the case being published in the press without fear of their taking legal action. I asked investigative reporter Shoshi Zaid to dig up the facts for me, and after expending much effort, she told me that the family is unwilling to comment. This case reveals an extreme yet not uncommon facet of adoptees’ choices. As for this point, I will say that I know two adoptees who not only would not agree to come forward with their stories, but did not even want to open their adoption files for various reasons, not necessarily sentimental ones.

In 2010, journalist Carmela Menashe revealed two astonishing stories, indisputably involving criminal acts, which took place in the same institution: Gil Greenboim was born in 1956 in Haifa’s Batar Hospital (a private hospital run by a Dr. Batar) to a woman of Moroccan descent who was told that her baby had died. She was then released from the hospital’s care. A month later, her very-much-alive baby was given up for adoption based on the decision of the hospital staff and the welfare office, obviously without her knowledge. Greenboim accidentally discovered that he was adopted. Atypical to such cases, his mother’s name was written on his adoption papers, but her signature was nowhere to be found. He found his biological family and made contact with them, but did not tell his adoptive parents until they lay on their deathbeds, as he cared for them devotedly until their demise.

Gil Greenboim was luckier than Dudu Dehan, who was born in 1969 in Batar Hospital to a mother of Moroccan descent. She was told that he died, after which he actually spent eight years in foster care. From there, Dehan was sent to a home for mentally handicapped children where he lived until he was 30, despite the fact that he did not suffer from any cognitive or psychological disabilities. Meanwhile, his court-appointed guardian never intervened to rectify this horrifying scenario. When Dehan was told by an employee in his institution that his parents were not his biological parents, he began looking for his mother, but was rejected at every turn, and was told that nothing was known about her (some people even told him that she was dead). But Dehan did not give up, and ultimately found her using his birth certificate. Astonished, she told him that when she’d asked to see her baby, a Dr. Margalit told her that he had died and refused her requests to see his body. A nurse who had been on duty at the time admitted that children born at Batar had gone missing, and as far as could be seen, had even been given to couples seeking to adopt who “placed their orders” in advance. A midwife added that they would routinely cover up the newborns so that their mothers could not see them, although she herself refused to comply. Remember, this was the 1970s: if such “solutions” and recklessness took place, and any voice of dissent hushed, think of how things were 20 and 30 years earlier.

Here’s another answer to the question of where the adoptees went: abroad. Despite the fact that even British Mandatory Law explicitly prohibits removing children outside their country of birth for adoption, such cases have been discovered dating back to the 1950s. In one such case, documented by Mashiach, a senior officer in WIZO residing in England used her connections to remove a girl from a WIZO institution in Israel for adoption. “She pulled strings and it worked,” says an employee of the institution. WIZO comes up again and again in these stories.

Many investigators have found adoptees abroad who have refused to “open the adoption can of worms.” But they’re not the only ones. In 1986, Arnon Navot served as police superintendent when he received a letter commissioning him to investigate the matter in order to establish an evidentiary foundation for a committee’s work. In an interview with Yossi Walter for Ma’ariv in 1995, Navot claimed that he was thwarted in his task. Nonetheless, he discovered damning findings. For example, clerks were discovered to have issued multiple death certificates for a single baby, each bearing a different name, thus enabling the certificate’s use for a live baby.

Among others, Navot found an individual in Belgium (after he had been adopted there) who the records show died in infancy. But many of the committee’s files were burned, and Navot himself was not permitted to investigate the matter of his own adoption.

In the Ma’ariv interview, he spoke unequivocally of the blatant rationalization for the abductions:

It all stems from the fact that the Ashkenazi clerks related to the Yemenites as animals who felt no bond with their children. ‘You have lots of kids. What difference will one less make?’ was heard by more than a few parents upon being informed that their child had died.

Shoshana’s story is extraordinary. While more complex, from both a personal and familial standpoint, than the scope of this article allows, her testimony contains a horrific angle: trafficking in children. Since she was not taken into foster care, Shoshana was left behind in an institution until a late age, where she bore witness to the most shocking case of all. Intelligent and alert, she wandered among “child merchants,” surrounded by Yemenite children who came and went without notice.

Shoshana and her twin brother were taken from their mother immediately after birth at Tzrifin Hospital (mentioned in Dr. Lichtig’s memorandum) and placed in a WIZO institution in Jerusalem, where they stayed until they were seven. There, along with many Yemenite children, they saw new children fill the empty beds on a regular basis. Most of the children were housed separately with no adult supervision until the war broke out – when the sirens sounded and the children were taken to bomb shelters. To her astonishment, Shoshana met children of light complexion who resided in the same neighborhood. Apart from the staff, who were all “white,” she never saw any adults the entire time she lived there, nor were the words “father” or “mother” uttered by any of the children.

At around age seven, Shoshana and her brother were taken to live in Gur Aryeh, an ultra-Orthodox institution in Bnei Brak, where again, all of the children were Yemenite. Every so often, they’d gather the children in one of the rooms – usually the one we used for prayers – and the door would open. ‘The American aunts’, as they were nicknamed, would enter. They spoke a foreign language. One by one, the girls would be called forward to be inspected by the staff. Then each girl would get back in line. Children regularly disappeared from Gur Aryeh, says Shoshana. Only during her stay there did she find out that she had a biological family, and was told that her mother had died five years after giving birth to her. If it was true, it is not hard to imagine that she died of heartbreak from never seeing her children. Shoshana refused to recount more than that; it’s an open wound, she says. More than 60 years later, it is still a living, painful trauma.

* * * * * *

The same week that Yaron London’s shocking article on the affair [Hebrew] was published, high school students took their history matriculation exams. The first part of the exam dealt entirely with the Holocaust: Hitler; the Wannsee Conference; the various stages of the Final Solution; anti-Semitism in Nazi Germany; the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, etc. Imagine if the exam also included the racist teachings of Arthur Ruppin and Ben-Gurion; the racist and discriminatory policies of the Ashkenazi establishment toward new immigrants from Arab and Muslim countries, the kidnapping of Yemenite children, the ringworm experiments on Moroccan children, etc.

The material covered in Part 1 of the exam touches on events that, while painful, are constitutive to Israel’s establishment. Therefore, learning them should be compulsory for several reasons: we believe that Israelis need to know these facts; if the state doesn’t make sure they are taught, they will be forgotten, and future generations will not feel the weight of their significance. While considerable effort is made on the part of the state to analyze and interpret the Holocaust, it acts with the same “devotion” to wipe out other injustices from memory – among them the abduction of the “lost” Yemenite children (as it is complicit in each of these atrocities). Despite the fact that the notion of “disappeared” Yemenite, Mizrahi, and Balkan children is so inconceivable and terrible in its proportions, what actually makes it dangerous, in the view of the establishment, is not the countless tragedies that it caused nor the suffering of the mothers. Rather, it is the active abetting of official entities that took part in this criminal deed.

The establishment of the State of Israel was tied up in powerful organizations struggling among themselves for influence, funds, and power: WIZO, the Jewish Agency, the Joint [Distribution Committee], the medical and legal elite, the Hevra Kadisha [Jewish burial society], Agudat Yisrael; Na’amat [Labor-sponsored Working Mothers’ Association], the kibbutzim. According to the testimonies in this affair, these are the very organizations that were complicit in the criminal act of the abduction of Yemenite children. Whether fueled by racist ideology, greed, or a front for the gain of certain benefits, these organizations’ names come up again and again in the testimonies of both parents and children, physicians and nurses, clerks and administrators – the vast majority of which are backed up by archives and documents. This is the DNA that forged Israel.

However, while this disgraceful chapter has been proven by evidence, it is not taught in any class – history or otherwise – to our children, who, as they grow to adulthood, believe that the entire affair is simply based on rumors, if not outright lies. The failure to teach and learn these truths leaves a vacuum that becomes fertile soil for denial. And who knows better than we – the nation built on the ashes of the Holocaust – the dangers of denial?

The abduction of the children of Yemen, the Middle East, and the Balkans is indisputably an ethnic-based crime – as was the ringworm affair, committed by Ashkenazim on Mizrahim – it is an open, bleeding wound whose dimensions are too large to be ignored. On the contrary: with each generation the awareness becomes stronger, along with the state’s role in the cover up, denials, and whitewashing. Meanwhile, the gaps between the Mizrahi and state narratives are still wide. These stories turn push us toward the understanding that the state cannot move on without resolving this affair in a way that will certainly be painful and difficult for all concerned – a process that as far as can be seen will compel us to renounce our beliefs and rebuild them from scratch.

The second part of the history matriculation exam dealt entirely with the establishment of the state up through the Yom Kippur War. One day, I hope students will be asked how the Mizrahi struggle for equality led to a shift in the perception of Zionism, and about the clauses of a future “reconciliation pact” dealing with the state’s acknowledgement of the gross injustices committed against families whose children were abducted. Mark my words: that day will come.

Thanks to: Dr. Rafi Shovali, Ofer Kochi, and Attorney-at-Law Rami Tsubari

Sources: Yigael Mashiach, Haaretz, Yehudit Yehezkel, Tzvi Alush, Gaby Baron, Oron Meiri, Smadar Partosh, Yediot Aharonot, Yossi Walter, David Lavie, Koby Bleich, Maariv, Shoshi Madmoni, Shishi, Carmela Menashe, Mabat Sheini

The author is a poet and social activist. This post originally appeared in Hebrew on Haokets.

Related:

The Yemenite Baby Affair: What if this was your child?