Just five minutes from Kfar Saba, under full Israeli control, children from the village Arab a-Ramadin will attend a school made of clay, without electricity, and most certainly without computers. All my years as a teacher and administrator couldn’t have prepared me for this place.

By Eitan Kalinski

As I stood in front of a structure called ‘School for the Children of the Village of Arab a-Ramadin,’ located five minutes from Kfar Saba, I felt myself shamefully shed over 40 years of teaching. A stone’s throw from Kfar Saba’s cultural centers and educational palaces to the west, and the settlement of Alfei Menashe to the east, stands a cramped condemnable clay structure with a gaping roof. We’ll call it a school.

In Kfar Saba, which as I mentioned is five minutes away from this school, the staff of teachers at every school is diligently undergoing final preparations to receive the students who will arrive to smart classrooms, laboratories for chemistry and physics, computer and robotics rooms, a gymnasium, spacious well-lit classes, air conditioning that will give you chills during heat waves, heating that will warm students when it’s cold, an expansive yard for recess, bathrooms and water fountains in the yard, and lockers and cold water in the corridors.I have been a teacher for over 40 years. I assumed managerial positions for several years and led a teacher’s seminar in Safed. All my organs associated with the education system suffered from shock on Saturday, when I left a tour with dozens of young members of Combatants for Peace and stood before this structure. I felt the intensity of a painful gap between what I experienced throughout all my years in the school system, and the trampling of respect for student and the teacher, which will take place on September 1 at the ‘gate’ of the Arab a-Ramadin school.

On the other hand, for the children of Arab a-Ramadin — located in Area C, under Israel full Israeli jurisdiction — a dedicated staff of teachers imbued with a mission to do the impossible, wait within the clay walls of the classroom. Under a gaping frayed ramshackle roof, three students will sit around one desk because of the shortage, and over 40 students will cram into one classroom. Rays of sunlight will shine through one tiny window to light the room that isn’t connected to electricity.

Inside the cage

Descriptively embroidered cloth caught my attention through the window, with remnants of lesson plans for seventh graders from the previous year depicting that science was the first lesson each Thursday. Second lesson: English; third lesson: Arabic; fourth lesson: sports; fifth lesson: literature; sixth lesson: geography. The seventh and eighth lessons were devoted to assisting those interested in receiving help with homework.

I admire the seventh grade science teacher who taught the second lesson on Thursday in conditions in which they could only tell stories about science, unable to introduce students to contemporary 21st century studies.

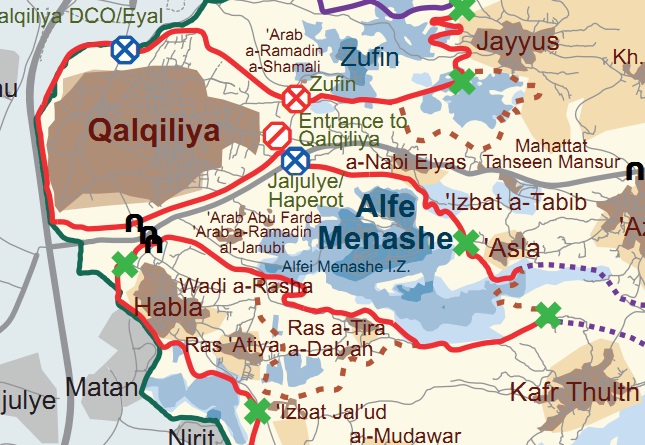

The village of Arab a-Ramadin is impossibly trapped: it’s in the West Bank, though disconnected from the rest of it by the separation barrier as it’s located on the Israeli side. One needs to travel through a checkpoint to get to the nearest Palestinian city, and to undergo a long and humiliating security check on the way back, including restrictions on the amount of goods that can be brought home. On the other side of the village Israel sprawls into Kfar Saba just around the corner, but the villagers aren’t permitted to cross the invisible border. So they find themselves trapped between the place where they’re permitted to be, but are physically blocked from entering, and the place open before them that they’re forbidden to enter.

On the chalkboard in the seventh grade classroom, a quote from a poem by Mahmoud Darwish remains:

I am an Arab

My ID number is

50,000

I have eight children

And the ninth is due after the summer

Does that anger you?

I am an Arab…

On the chalkboard in the seventh grade classroom, a board urgently in need of new life, remains a quote from another of the poet’s poems:

Leave our wounds

Our land

Leave the aridity

The sea

Everything…

Leaning on my cane I could hardly stand up, so I stayed in place for a good hour reciting Bialik’s poem to myself:

Should you wish to know the Source,

From which your brothers drew…

Their strength of soul…

Their comfort, courage, patience, trust,

And iron might to bear their hardships

And suffer without end or measure?

Should you wish to know the source from which the children of Arab al-Ramadin draw courage and strength of soul to suffer without end or measure at the ‘madrasa,’ it tends to fall in the center of the village. Dilapidated buildings symbolize the determination of the villagers to continue clinging to the land on which they’ve stayed since 1950, after some were expelled and others fled in panic in 1948, from Be’er Sheva and the surrounding area. Israel has wounded the beautiful view on the way from Kfar Saba to Alfei Menashe with barriers and fences, as it needed a road ethnically clean of the Palestinians legally living there since the days of Jordanian rule.

I was a young proofreader at a newspaper called Voice of the People, when in 1955 the educator Nimer Marcus, brought his 14-year-old student Mahmoud Darwish, from the village of Kafr Yasif to Tel Aviv for a meeting with the poet Alexander Penn, the editor of Voice of the People’s literary supplement. In this meeting that took place in the editorial staff’s cramped room, the poet Alexander Penn saw it fit to steal away from his work to read excerpts from the poems ‘In the presence of the bookcase,’ ‘City of killing,’ and ‘On slaughter,’ to the young Mahmoud Darwish, in his booming voice that shook the walls. I remember Penn’s exchange with the young Darwish to this day: “We must learn to accommodate one another’s pain.”

In Arab a-Ramadin resides a population determined to hold on to its land, drawing power from Mahmoud Darwish’s poetry. Opposite them stand the Civil Administration’s armed forces, seeking to displace them from their land.

Eitan Kalinski is a retired Bible teacher.This article was originally published in Hebrew on Local Call. Read it here.