Fifteen years since the events of October 2000, in which Israeli police killed 13 Arab protesters, Hassan Jabareen, head of Israel’s leading Arab civil rights organization, talks to +972 about the lessons Israel’s Palestinian population learned from the killings, the escalation of systematic discrimination since, and the vision of a democratic state of all its citizens. ‘If Arabs in Israel determined their political leanings in accordance with what Jews said, they would always be inferior.’

The Arab public in Israel this week marked 15 years since protests that resulted in the police killings of 13 people and left hundreds wounded. “October 2000 led our public to understand that the existing parliamentary and legal tools are not enough to defend our rights,” says Attorney Hassan Jabareen, founder and executive director of Adalah, in an interview to +972 Magazine. October 2000, Jabareen explains, was a pivotal moment for Palestinian citizens of Israel, one that changed the way they viewed the State of Israel and forever altered their political relationship to it.

Only five years after establishing Adalah when the events broke, Jabareen led the legal team that represented the families of the victims in commission of inquiry appointed by then Supreme Court Chief Justice Aharon Barak (also known as the Or Commission). Since then, Adalah has become the leading legal advocacy organization for the Arab minority in Israel — more than 1.6 million Palestinians (21 percent of the population) who are Israeli citizens.

Over the years, Adalah has filed a long series of petitions demanding equal rights and equal distribution of resources for the Arab minority. Many of its cases resulted in landmark rulings. Adalah has also challenged, unsuccessfully, a new wave of legislation targeting Palestinian rights and political activities in Israel: the Nakba Law, citizenship law, the acceptance committees law that legalized housing segregation, and the anti-boycott law. Jabareen himself led the representation of Palestinian members of Knesset who were disqualified from running in elections (he won in every case), and the defense of Arab public figures facing criminal and political persecution.

Jabareen is the attorney for the High Follow-Up Committee for Arab Citizens of Israel and an attorney for many Palestinian members of Knesset. Former High Court Chief Justice Aharon Barak once called him “one of the most important constitutional attorneys in Israel.” He was part of the team that published the Haifa Declaration in 2007, which presented the Arab-Israeli public’s vision of for “a democratic state for all its citizens.”

In our conversation, Jabareen revisited the events of October 2000, what has — and hasn’t — changed since, and discussed the prospects of civil equality in Israel.

What had you been working on in the months leading up to October 2000?

We entered the new millennium with a certain degree of optimism. Those were the glory days for civil society organizations, when Adalah and other Palestinian rights organizations inside Israel, the West Bank, and Gaza were founded. Talks between the PLO and the Israeli government were looking serious and we thought we were nearing the end of the occupation. Momentum could be felt around the world. New democratic regimes were being established, apartheid fell, the Berlin Wall fell. We knew we were living under a institutionally discriminatory regime, but there was hope. The events of October 2000 surprised us.

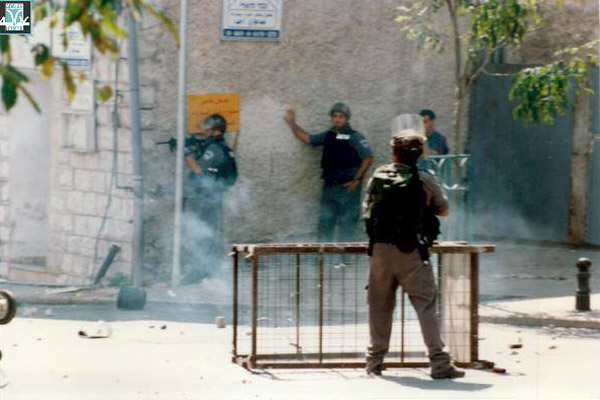

Palestinians in Israel were used to political protests, but we hadn’t had intensive experience with people being killed during demonstrations since Land Day in 1976, when six people were killed in Sakhnin and Arabeh. We thought that was behind us. I was at a demonstration at Umm el-Fahm, that’s where the first victim was killed. I saw people’s reactions. I felt the anger. I was there at Rambam Hospital the moment Wissam Yazbek from Nazareth passed away. I was next to his mother when the doctor came out and broke the news that her son had died. I will never forget that moment.

How did you understand the incidents at the time?

As a member of a human rights organization, what preoccupied us most was how to react: how we could do our utmost to provide legal protection to protestors, and how to raise awareness of the killings. We got 500 Palestinian lawyers to represent, pro-bono, all those who were arrested. We published a few sharply worded press releases — in Arabic, Hebrew, and English — accusing the prime minister, the public security minister, and the police commissioner of murder. We blamed Israeli society for not reacting. We stand behind every word. We wrote back then that [the killings] simply were not justified. After investigating the incidents, it was clear we were right. The Or Commission later confirmed all this.

The Jewish public was also taken by surprise. What do you tell people who believe Arab citizens joined the Intifada on October 2000?

The events began with Ariel Sharon, then head of the opposition, going up to the Temple Mount, where Al-Aqsa Mosque is located, which was designed to harm negotiations between the PLO and the Ehud Barak government. There is no dispute about this. Border Police used enormous firepower there and those images resonated deeply among the Palestinian-Israeli public. In response, the High Follow Up Committee for Arab Citizens of Israel called a general strike among Palestinian-Israelis — an obvious response, in my opinion.

The strike could have ended like any other. To remind you, strikes were also called in December 1988, which were widespread demonstrations in solidarity with the events of the First Intifada. Nothing happened back then. But this time, the government’s use of lethal force in Wadi Ara triggered an escalation. If the police had allowed people to protest, everything would have turned out differently. Even if Wadi Ara’s highway had been shut for a few hours. By the way, the police tolerate such closures every now and again, sometimes even with prior coordination with some of the Arab MKs. That confirms that it doesn’t always have to end the way it did in October 2000.

The solidarity Palestinian-Israelis demonstrated with fellow Palestinians was legitimate. It was done peacefully and civilly. No one used live ammunition. Out of the 800-page Or Commission Report on the events of October 2000, not one incident is mentioned in which an Arab used live ammunition.

Still, roads were blocked. Stones were thrown at innocent drivers.

It is permissible for minority or depressed groups to block roads to protest certain incidents. Democracies allow marginalized groups to protest sometimes in ways that fall outside the framework of the law. Only a fascist worldview would insist that one must fulfill and obey the law at all costs. Clearly it’s not permissible to hurt others while engaging in protest but you can allow roads to be blocked and traffic upset in exceptional cases. The State of Israel is very far from this democratic view of things, especially with regard to us Arabs.

The problem isn’t Arab protesters. The problem is that the Israeli public sees them as an enemy against which force must be used. The police use lethal force against Arab protesters not by chance, but because the police are part of the Jewish public and internalize its racism. Of course there are members of the Israeli public who oppose this sort of hostility toward Arabs, to the use of violence, and who support equality, but these are a minority. The majority does not distinguish between legitimate solidarity and violence — the only question being if you are Jewish or Palestinian. That’s the determining factor. That’s why the October killings had racist underpinnings.

Didn’t the protesters put peoples’ lives in danger? Is that not the context of the shooting?

The Or Commission heard 434 testimonies. It reviewed tens of thousands of documents and a large portion of police and Shin Bet intelligence reports. They visited sites where people were killed and evaluated each incident individually. After all this, it stated unequivocally that not one murder was justified. Not one. It confirmed unequivocally that the police used excessive force in violation of the rules of engagement. The committee condemned the use of snipers and live fire.

It is true that during the “eight days of October” there were severe incidents. Some Jewish drivers were pulled out of their cars and were harmed, and one Jewish citizen was killed near Jissr a-Zarqa. But these were isolated and exceptional incidents. The Follow Up Committee condemned them vehemently and immediately. The dominant picture from those days, alongside the death of 13 [Arab] youths and the wounding of countless others by the police, was injury and persecution of Arabs by Jewish citizens in Nazareth Illit, Tiberias, Acre, Lod, and Ramle.

Yom Kippur October 2000 was horrific. Jews went out and attacked Arabs — some even used knives. They terrorized Arab shops and workers. In Tiberias they tried to destroy an old mosque. The authorities focused on arresting and prosecuting hundreds of Arabs, but they were very indifferent toward Jews who harmed Arabs.

How do Palestinian citizens of Israel understand October 2000 today?

Many things have changed since then. The separation barrier was erected; Gaza was placed under siege; the West Bank became more disconnected. New laws against the Arab public have been introduced in Israel; family reunification for Arab families in Israel was abolished by the Supreme Court itself; the Nakba Law; the acceptance committee law. We’re living in a different reality.

Palestinian citizens of Israel have come to the conclusion that legislative and legal tools are no longer sufficient in safeguarding their status. Thus, since October 2000, you see more efforts being dedicated to international advocacy; to appearances in front of international committees, meetings with foreign embassy representatives in Tel Aviv, advocacy before the European Commission and various UN committees. The aim is to get the international community more engaged in order to safeguard the status of Palestinian citizens of Israel.

We cooperated with the Or Commission, despite concerns and reservations. We expected legal proceedings. It was the attorney general’s decision to close the investigations against police officers that led us to the decision to appeal to the international community. In years prior, there had been Arabs who opposed turning to the UN and the international community. But after the [internal] investigations were shut, international advocacy became part of the consensus.

In the years that followed, the Arabs of Israel published a series of vision documents that acknowledged the structural hostilities of the state vis-a-vis its Palestinian citizens. We emphasized our Palestinian national identity and cited the Nakba as a formative and central component of Palestinian identity. The documents were highly influenced by the events of October 2000.

From a Jewish perspective, this process describes a certain narrative whereby the Palestinian citizens of Israel detached themselves from the state in October 2000 and then anchored this detachment in the documents outlining their vision.

I understand how it’s possible to see it this way if you subscribe to Israeli consensus worldviews. The decision to engage in international advocacy is seen as hostile because the belief is that Arabs ought to be submissive and accept the foundations of the regime, primarily its constitutional foundations of being a Jewish and democratic state, and to act accordingly. We reject this.

This is not just my personal opinion, this is the opinion held by the vast majority of people active in civil society, the political parties, and the members of the Follow Up Committee. We do not accept Israel’s ethnic constitutional foundations; instead we strive for a democratic state for all citizens. If Arabs in Israel determined their political leanings in accordance with what Jews say, they wouldn’t even be able to ask for equality; they would continue being inferior.

In retrospect, the Or Commission emerged as an act of readiness on the part of the government. It’s hard to imagine such a commission being appointed or operating today.

Correct. Despite our criticism of certain aspects of the commission’s work, and our claim that the commission didn’t have the courage to explicitly cite the names of the police commanders guilty of murder nor recommend that they be indicted, it did a serious job, especially given the prevailing political context and attacks by government ministers criticizing its legitimacy. The commission addressed the issue of discrimination in depth in its conclusions. And it tried to argue for criminal investigations into those involved in the killings.

Fifteen years later, the Or Commission looks like an institution alien to this state. And I use the term ‘alien’ in a positive sense. There was an opportunity with the commission, but it was missed.

Has that led you to have second thoughts about your work with the commission?

Before deciding to work with the Or Commission, a delegation from Adalah traveled to Northern Ireland to confer with lawyers who had a similar experience with a commission that investigated the events of Bloody Sunday, and to South Africa. We were concerned not only about the crushing nature of the events, but also that they would eventually blame the Arab public in Israel of what happened.

Although we did not have high expectations, we decided to use the commission so that we would have a platform to present personal stories, gather testimonies, present the claims of victims, and scrutinize police testimony. We opted to use the proceedings as a means of empowering us from within, as a society, regardless of what the outcome of the proceedings. Thus, we always stated at hearings that we already knew who the culprits were.

No one was indicted as a result of the Or Commission. On the contrary, the only charges filed by the attorney general were against the victims: against the father of a slain victim who attacked police officer Guy Reif during commission proceedings; the brother of one of the victims who stated after his brother’s investigation was closed that he himself would kill whoever killed his brother. In this respect, despite the professional and intensive work we did, we did not succeed. The racism of law enforcement officials was stronger than the rule of law.

Despite all this, I am not sorry about the work we did. If we hadn’t appealed to the Or Commission, we would not have amassed over 400 testimonies, which Adalah later released in reports. We would not have been exposed to testimonies by policemen. We would not have received over 4,000 pieces of evidence. We wouldn’t have an extensive record of each one of the killings. We would not have had an 800-page Israeli report stating that the police were hostile toward the entire Arab public. We would not have a report that states the events took place against a backdrop of historical discrimination against Arab citizens.

Do you still believe today in working together with Israeli institutions? In petitioning the Supreme Court?

One must distinguish between the necessity of using the law and legitimizing norms of oppression and discrimination. Human rights organizations have always used legal means. Slaves also represented their issues to the American Supreme Court. In South Africa, they turned intensively to the judicial tribunals. Residents of the West Bank and Gaza, Northern Ireland. None of those examples suggest that turning to the courts on behalf of victims provides legitimacy to the system, or that it is the only way to struggle against oppression and achieve equality. It is just one method of many.

The court serves the regime and the law is just one aspect of the politics of the Jewish consensus, especially when it comes to the Palestinians. We are working to change our position [in society]. And precisely out of an understanding of the connection between law and politics, politics also seeks change though the courts.

You probably know that most Israelis consider Israel’s High Court of Justice to be ‘leftist’?

I do not measure my values on a Jewish-Israeli scale. In recent years, the High Court has surrendered more and more to the Israeli consensus, rejecting petitions that were completely just. This is how it upheld the Acceptance Committee law, the Nakba Law, the anti-Boycott Law, and the most racist law of the past 20 years, the law banning family reunification.

It is highly doubtful whether the current High Court would have written today the Ka’adan ruling. Decisions that contradict the Ka’adan decision are being handed down these days. The ruling on the village of Umm al-Hiran is a colonialist ruling. Instead of saying that Arabs have the right to live with dignity in their villages, it rules that it is permissible to banish Arabs from villages inhabited for over 50 years in order to build Jewish townships. The Umm al-Hiran ruling should be used to teach a course about the linkages between law and colonialism.

In the past, I’ve heard Palestinian intellectuals claim that the laws against Palestinian Israelis are the Jewish public’s push-back to the vision documents and the attempts of Israeli Arabs to take their Israeli citizenship seriously, with regard to all the rights citizenship confers. In other words, until the 1980s, Palestinian citizens of Israel didn’t really internalize the fact that they were Israeli citizens, and once they realized this and started to struggle for their rights within Israel, the Jewish public became stunned and started consolidating its discrimination into additional laws. What’s your stance on this?

What you’ve just quoted is the account that most Arab intellectuals and academics in Israel ascribe to. I don’t agree with it. It’s not that “they didn’t take citizenship seriously” in the 1950s, it’s that it was a struggle for survival back then with regard to preventing deportation, home demolitions, land expropriation, and military rule. In the 1950s and 60s there was an Arab national consciousness in Israel. Back then the state was racist as well, but the political consensus was different.

It is not possible for Arabs to adopt their Israeli citizenship in its entirety. To take citizenship seriously, in its entirety, is to fight for full equality, equal rights and duties in all domains. For example, to fight for military service and advancement within the military, so that we are represented among the top officers, or in the Foreign Ministry, or so that we have seats on the Knesset Foreign Affairs and Defense Committee. But Arabs won’t demand that and Adalah will never submit a petition making that demand because the current regime does not guarantee equal citizenship at its core, not even in theory. I do not know a group of natives in modern history who fought for equality in all domains, including integration, before regime change occurred and their rights were recognized. The struggle of Arab citizens is first and foremost to change the regime to a democracy for all its citizens, and end to the occupation.

Adalah does seek achievements that address equality and dignity in daily life. That’s why our court petitions demand equal budgets and fight discrimination or land expropriation. But we won’t ask for an equal distribution of Palestinian refugee property, for example. And when Jewish-Mizrahi intellectuals call for equal distribution of the Kibbutz-owned lands, they are asking to distribute what was taken from the Palestinians. We aren’t part of Israeli wars and won’t ask for equality in the distribution of spoils from these wars. We are the victims of these wars.

You can’t take part in dispossessing and revoking the right of return of your fellow people. You cannot be a Palestinian soldier in a Jewish army that is occupying your people. You cannot be an ambassador of a government that occupies. You have to fight for dignified life.

But there is a Palestinian consul and there are Palestinian soldiers…

I’m referring to the call for equality, a process of political parties, leadership and civil society, not to individuals. Those aren’t Adalah’s struggles. We cannot be equal in a regime that is based on denying our identity. You can’t join the machine that is suppressing your people. A blind call for civil equality that ignores the right to live with dignity is not a true call for equality; it is merely an illusion.

Why shouldn’t Palestinian national identity and group rights be expressed in a Palestinian state? The State of Palestine could extend self-determination to all Palestinians in the world, while Palestinian-Israeli citizens of Israel would be entitled to full civil rights and equality in the State of Israel, as a Jewish state.

This is what liberal Zionist philosophers claim. When I hear that, I laugh. To whom will we pay taxes? To the Palestinian Authority that safeguards our national rights, or to the Jewish state? Where will we be able to work as ambassadors? In our nation-state or in the Jewish state? What parliament will we be a part of? And if there is a vote in parliament regarding national matters, will it be possible for Arab members of Knesset to participate in the vote? Which regime, the Palestinian or the Jewish one, will set the curricula of our schools? Who will decide which religious holidays and national holidays are given during the school year? What about the status of Arabic? Where will the Al Midan Theater get the funds to do plays depicting Palestinian life? The idea you suggest necessitates three types of laws in the Jewish state. One for Jews, one for Arabs, and one for citizenship. This is apartheid par excellence.

Zionism wanted to gather all the Jews in one territory. The idea was that only in Palestine would you would have a national and civil life for Jews. Here, freedom and autonomy would be realized. Thus it was possible to say to Jews in the world: if you want full rights, go to the state of the Jews. By the way, this is what Netanyahu said when he invited French Jews to immigrate to the Jewish state after the events of Charlie Hebdo. This is also what the liberal Zionists say to us today. But this idea that states uphold the civil rights of only one ethnic group, that is the racist idea that prevailed in old Europe. A Jew is entitled to full civil rights in France as well. Citizenship doesn’t get split apart by territory or regime. The idea of an ethno-nationalist state is anachronistic. It has a dreadful past, and it has no future. And this is without even saying a word about the point of departure of our discussion. We did not immigrate to Israel, it immigrated to us.

On a more personal level, you are 50 years old and you’ve been involved in civil struggles on behalf Arab-Israelis for more than 20 years. What is the thing that most worries you today?

Civil war. First and foremost, what’s going on in Syria, but also in Iraq, Libya, and Yemen. This is a very difficult situation. Every Arab man or woman who hopes for a better life is thinking about that right now. The situation in Syria does not mean that I am abandoning the struggle against the occupation or the fight for a life of dignity here; but on a personal level I acknowledge that this is what worries me most today. This is the thing that more than 300 million Arabs are talking about, including Arabs in Israel.

Translated from Hebrew by translated by Gila Norich.