From its origins until today, liberal Zionism has been unable to reconcile Israeli policies of dispossession and military control with the image of a democratic state. Is it merely a matter of semantics, or inherent to the ideology? Part two of Ran Greenstein’s analysis.

By Ran Greenstein

As discussed in the previous part of this article, liberal Zionists like Arthur Ruppin and Hans Kohn responded in divergent ways to the challenge of reconciling broad universal values with narrow Zionist aims. What they shared with other activists and intellectuals, though, was full realization of the costs involved in their choices. This is not the case for most present-day Israeli liberals, who take the post-1948, post-Nakba realities for granted, as the starting point for looking at the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

One way of looking at the dilemmas facing liberal Zionism today is through the notion of denial, or the refusal to acknowledge historical context, which continues to shape our political scene. This context reflects long-term processes and can be broken down by the key dates with which these processes are associated. In each case they built on existing trends to set in motion a new round of developments that shaped the subsequent period. Let us consider each in turn and discuss their implications.

The denial of 1917

This was the year of the Balfour Declaration, which asserted British support for the quest of the Zionist movement to establish “a national home for the Jewish people” in Palestine, based on the understanding that “nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities” in the country. It set in motion a process of mass immigration of Jews into the country and the re-construction of the Jewish community as a separate political entity, on its way to independent statehood. It also led to the formation of a Palestinian-Arab national movement, which opposed immigration and land acquisition by Jews, and demanded democratic government based on majority rule. The growing conflict between these mutually exclusive forces led to the 1947-48 war, the Nakba and the creation of the State of Israel.

Liberal Zionists deny that the Balfour Declaration was illegitimate from the perspective of Arab residents of the country, until then the unchallenged majority of the population. The British subordinated their prospect of independence to that of a new group of immigrants, and facilitated the creation of a ever-growing zone of social and economic exclusion, from which all Palestinians were barred (as rights-bearing residents, employees, tenants). Their natural response was resistance. It is hard to think of a single group of indigenous people in history who reacted differently to a similar situation. Yet, the liberal Zionist perspective finds it impossible to contemplate this basic reality, as it would raise questions about settlement and dispossession, colonialism and indigenous rights, which cannot be answered easily within its paradigm.

The denial of 1947

The UN partition resolution, which called for Palestine to be divided into Jewish and Arab states, was supported by the Zionist movement and the majority of Jews, and rejected by the majority of Arabs (in Palestine and elsewhere). One of the core beliefs of liberal Zionism is that these attitudes reflected the logic of compromise, which was adopted by Zionism historically, but was abandoned after 1967 and needs to be restored today. In contrast, the Arabs adopted a rejectionist position that undermined their chances to gain independence then and ever since.

In what way does this way of looking at 1947 constitute a denial? Seen from the perspective of the time, the partition resolution was inequitable. It granted the Jewish community territory it did not possess and took from the Arab community territory it did possess. Only 10,000 Jews – 1.6% of the total Jewish population – were expected to live as a minority in the area allocated to Arab state while the equivalent figure for Arabs in the Jewish state was 400,000 – 33% of their total. Jews, a third of the population, were allocated 56% of the territory, while Arabs who were two-thirds of the population were allocated only 44%.

Read more: The perennial dilemma of liberal Zionism

Beyond the specific details of the resolution, it gave a seal of approval to a process that had seen Palestinians losing their overwhelming demographic and territorial domination, unable to block the rapid growth of the organized Jewish community, and marginalized in their own homeland. Rejecting partition did not lead to a positive outcome for them, but they could not agree to have large chunks of their country given away to a group of people they regarded as unwelcome guests, most of whom had been there for less than a generation. That the foremost leader of the Jewish community at the time had built his career on opposition to sharing land, employment and residence with local Arabs, did not help build trust in a future under Jewish rule or alongside an expanding Jewish state.

The Nakba that followed the partition resolution was, in a sense, a self-fulfilling prophecy. Ethnic cleansing was both a result of the actions of Zionist forces, putting into effect plans for creating a contiguous defensible Jewish territory, and the re-actions of Palestinians, at times anticipating violent expulsion by fleeing the advancing military forces. The crucial point is that regardless of the circumstances of their departure or their participation in the events (as militants or peaceful residents, who were passively cleansed or actively fled their homes), all those who became refugees in 1947-48 were denied re-entry into the new State of Israel. The result was not merely the displacement of large number of people but the destruction of an entire society.

The liberal Zionist paradigm can digest these events only as the tragic but ultimately fortunate outcome of the quest for Jewish national self-determination. That it transformed the conflict into a struggle for restoration of people and their rights, forever marking it by the imperative to redress the “original sin” of dispossession, cannot be contemplated however. Rather, we need not dwell on the past, move on with our lives and wait for the “salmon syndrome” – using Ehud Barak’s horrible phrase – to die out.

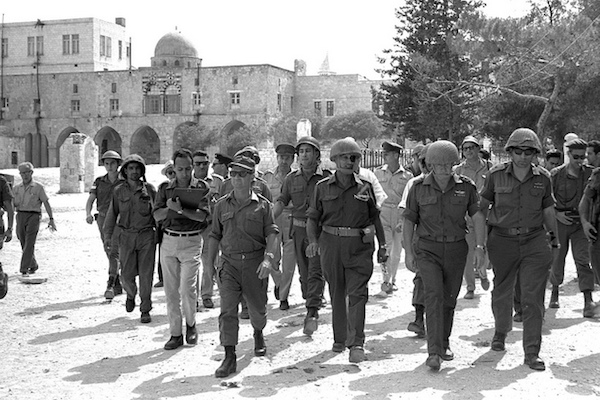

The denial of 1967

It is only with the war of 1967 and its aftermath that liberal Zionism truly came into its own. It deserves credit for having opposed the occupation, settlements and creeping annexation for decades. Is it fair then to charge it with denial? The answer is yes. Let us examine why.

The liberal stand against the occupation suffers from its refusal to consider the historical context of 1967, seeing the war as an aberration, a disruptive force that changed democratic, egalitarian little Israel into a right-wing oppressive state dominated by messianic settlers. Missing from this picture is the extent to which pre-1967 Israel was an oppressive state towards groups excluded from the mainstream: Palestinian refugees who were denied physical and political presence; Palestinian citizens who were physically present but also absent from full-fledged citizenship, having been subject to military rule and massive expropriation of their land; Mizrahi Jews who were given political rights but remained socially and culturally marginalized.

Exclusionary practices developed in the pre-67 period (in some instances – secretive methods of land acquisition and dispossession – already in the pre-48 period), were extended to the occupied territories, with some important modifications. The ethnic cleansing and the massive destruction of villages in 1948 were not repeated on the same scale in 1967 (though about 300,000 fled or were expelled from the newly occupied territories into neighboring countries, many of them refugees from 1948). The residents of the territories were allowed to work in Israel but were denied civil and political rights. Land was confiscated (and continues to be to this day) but on a smaller scale than what was expropriated from Palestinian citizens in post-48 Israel.

The resulting system of control is unique, yet displays many family resemblances to other oppressive Israeli practices, which were applied – to varying degrees – to different groups of Palestinians. It is the refusal of liberal Zionism to see the continuity between such practices, and the links they form within a common logic of exclusion, that constitutes denial. A struggle against the occupation that regards it as a mere territorial dispute, and refuses to consider its ideological and historical foundations – what Meron Benvenisti refers to as the “genetic code” of Zionist settlement – is bound to fail.

The denial of 1987

And yet, there was a period of time in which liberal Zionism seemed to be winning. With the First Intifada of 1987 and the processes it facilitated, culminating with the Oslo Accords of 1993, awareness of the occupation and support for its termination were at an all-time high. It was just a matter of time until the process of Israeli withdrawal was completed, so believed many liberals, and a genuine two-state solution would come into being.

As we learned in subsequent years, this widespread expectation failed to materialize. Instead of coming to its end, the occupation has shifted shape from direct to indirect rule, shedding responsibility for the welfare of its subjects, and excluding them even further from any share in the rights and resources associated with citizenship. While Israel has entrenched its control over the territory and material resources (agricultural and residential land, water and so on), occupied Palestinians have faced more serious restrictions on their movement, political organization, and ability to run their lives than ever before.

What was presented until then as a temporary military rule for ‘security’ reasons, has hardened into a mode of rule combining permanent inclusion of land and resources for the use of military and civilian authorities, catering exclusively to Jewish settlers, with the permanent exclusion of indigenous residents as rights-bearing citizens. In other words, an apartheid-like system that enshrines radically different levels of access to entitlements and resources based on ethnic-religious distinctions.

Not surprisingly, the response of liberal Zionists has been characterized, once again, by denial. Instead of coming to terms with the new realities, and developing appropriate strategies that would take into account the changing modes of rule, settlement patterns and demographic conditions, they continue to recite in vain the mantra of separation of Jews and Arabs in their own states.

The fact that the conflict can no longer be seen as merely territorial in nature (if it ever were so) makes no noticeable difference. All changes are eternally deferred to an indeterminate future, when Jews will become a minority (as if domination of 51% of the population over the other 49% were more legitimate than the reverse), when Israel has to choose between its ‘democratic’ and ‘Jewish’ aspects (as if ruling for half a century over millions of people denied political rights had not decided the matter already), when the prospect of a two-state solution is no longer viable (as if 20 years of futile diplomacy, resulting in entrenching the occupation were not enough), when the window of opportunity for a negotiated solution is closed (as if it were still open).

What is the essence, then, of the liberal Zionist denial? It is the refusal to recognize anything that makes the Israeli-Palestinian conflict unique and different from normal territorial conflicts: the colonial origins of initial settlement, the dispossession of 1948, the historical logic of exclusion, the permanent nature of the “temporary” occupation. As long as our well-published liberal Zionists continue to ignore such foundations of the conflict, their feigned anguished calls for a change of policy on moral grounds will remain little more than empty rhetoric.

Related:

The perennial dilemma of liberal Zionism

Can one be a liberal and a Zionist without being a liberal Zionist?

Ran Greenstein is an associate professor at the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg. His book Zionism and its Discontents: A Century of Radical Dissent in Israel/Palestine will be published by Pluto Press, UK, in October 2014.