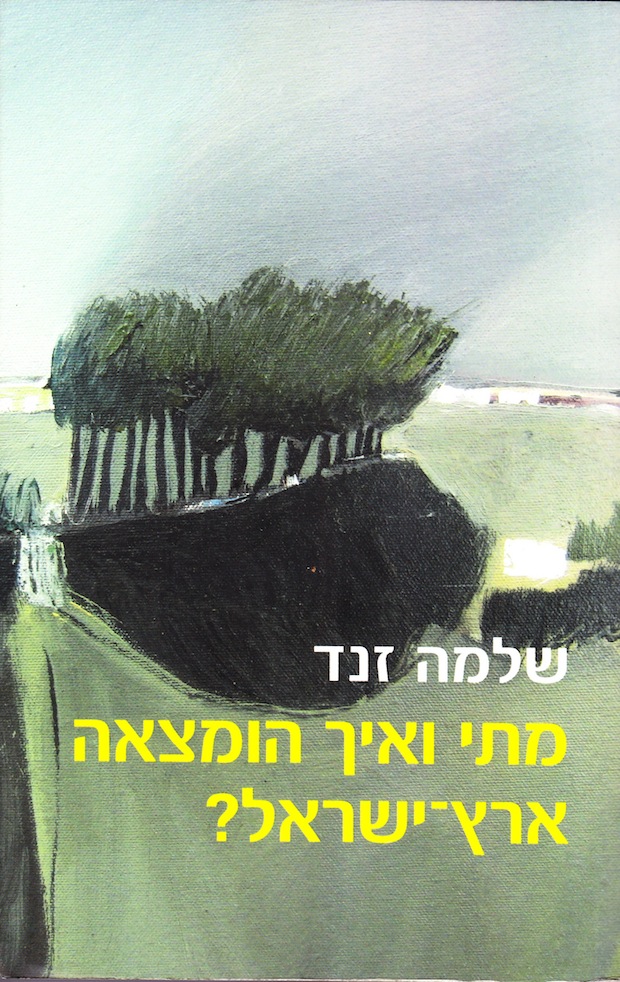

A review of Shlomo Sand’s “The Invention of the Land of Israel” and other musings on religious Zionism.

“After the people was exiled from its land by force of arms, it kept faith with it in all the lands of its diaspora, and never ceased from praying and hoping to return to its land and renewing in it its political sovereignty.” Among the many falsehoods contained in Israel’s Declaration of Independence, this must be the most baseless, yet you can hardly describe the core of Zionism without it. After dedicating his earlier book, “The Invention of the Jewish People,” to debunking the notion that there is a Jewish nation, and the lie that it was “exiled from its land by force,” Sand now turns attention in his new book, “The Invention of the Land of Israel” – to the second part of that sentence.

[whine] I’ll begin with a technical remark. Israeli publishers are sadly behind the times when it comes to digital books. Reading a book on the Kindle is a completely different experience than reading the dead tree edition: you can mark the text and keep it for future reference without damaging the book itself; you can easily copy relevant parts and quote them; and you can write remarks as you read, and read them later. I’ve been using a Kindle for two years now, and every time I have to crack open a codex I feel like I’ve been kicked back to the 19th century. Yet there is no proper Hebrew e-reader. [/whine]

Whines aside, this is a much better book than the first one; that book was published by the highbrow (read: poseur) Resling publishing house, and was accordingly tongue-tied and heavy on jargon. This one was published by a popular publisher – Kineret, Zmora Bitan – and now we see Sans at his prime, his writing much better and clearer than in “The Invention of the Jewish People.” Sand knows how to tell a tale and leaves the reader gripping for more.

The heart of Sand’s thesis is the intentional confusion in Zionism between the Halachic – Jewish law – concept of Eretz Israel (“The Land of Israel”, EI) and the concept of a place which is under Jewish sovereignty, and yearning for such a place. “Eretz Israel” is, originally, a Talmudic concept – not a biblical one – which delineates it as a territory that imposes extra religious obligations on Jews living in it, which Jews living outside of it are unburdened of. Talmudic legend grants EI various mystical qualities (wisdom, beauty and other nonsense which could only be written by people who haven’t lived here), but does not refer to EI as the “homeland ” of the Jews, and neither does it require them to live in it.

Judaism is of no homeland. It is a religious movement which can exist anywhere, whose last territorial anchors were cut down with the destruction of the Second Temple by the Romans in 70 AD. Were contemporary Judaism what Zionism later made it out to be – a people living in their homeland – it would have suffered a terrible shock. And while many were horrified by the destruction, and while a few haunting mourning poems were written in Greek or Aramaic, Judaism survived the destruction of the Temple amazingly well.

Most of the Jews in the world at the time – Sand quotes Philo of Alexandria on the issue – did not consider either Jerusalem or Judea their homeland, which is quite natural as they were not born there; and they didn’t think of EI at all. They made pilgrimage – or, rather, sent envoys on pilgrimages on their behalf, and sent their contributions with them – but they never saw it as a political center. When Judea erupted into insurrection in 66 and again in 132, it received no support worth mentioning from the rest of the Jews. The Sadducee priesthood class lost all its power, but the Pharisees prepared the ground well: every Jewish community already had its “minor temple,” the synagogue.

Pharisee Judaism, which would in time morph into rabbinical Judaism, made a shady deal with their Roman overlords after the destruction of the Temple: they would lead the people with Roman support, and a descendent of Hillel the Old would serve as patriarch (Nasi, in Hebrew) until 415. The rabbis kept their part of the deal: they did their best to tame Jewish nationalism. They turned the messiah, formerly just a successful warrior king – king because of being a successful warrior – into a being of marvel, super-human and inhuman, so as to avoid the misfortune of ever seeing one. The messiah, after all, is supposed to return the world back to what it was before the rise of the rabbis: a temple, sacrifices, and gleefully smirking priests back in their station. Can’t have that.

As part of this process of taming, the rabbis came up with the Three Vows, which forbade Jews from massively emigrating to EI, forbade them from rebelling against the nations of the world (it’s worth noting the rabbis, servitors of the emperors, gave divine sanction to their rule), and the third vow is directed at the nations: “That they should not enslave Israel too much.” Rabbinical Judaism left EI behind. Sand quotes some later rabbis who opposed emigrating to EI since the Halachic demands on those living in it are very high, and failure to meet them would make the land impure.

Thus, while hordes of Christian pilgrims flooded the country, the number of Jewish pilgrims coming to see the land which they supposedly ” never ceased from praying and hoping to return to” was miniscule. The noted Hebrew writer Boaz Evron’s book “Ha’Heshbon Ha’Leumi” seems to breathe life into every page of Sand’s book. Evron used to quote A. B. Yehoshua, who wrote in despair that, judging by medieval and early modern travel books, Jews seem to have made every effort to avoid EI; they often travelled around it.

Until nationalism came around, and Eastern European nationalism was possibly the worst. Intolerant and often murderous, its arrival sent a large number of Jews – always a convenient scapegoat – away. Millions of the Jews of Eastern Europe fled to the Americas, mostly to the US. A significant number of the remaining either joined or formed socialist or communist movements, and many became ultra-Orthodox, rejecting modernism in all its forms. A small minority formed the Zionist movement.

The rabbis have, as a rule, rejected it and persecuted it with fury, both Orthodox and Reform. The first because they saw how Zionism twists Judaism into a nationalist heresy which greatly resembled the nationalist movements of Eastern Europe. This was no accident: Zionism and anti-Semitism were, and to a large extent still are, mirror images of each other, both accepting the axiom that Jews have no place in Europe and that they must be “returned to their homeland.”

This baseless concept – most Jews living today have nothing to do with the Jews living in Palestine in the Roman era as those have long ago converted – is what made Reform Judaism an enemy of Zionism. Taking a page from Philo, the Reform rabbis stated Jews were loyal to their actual homeland. And by returning to Philo’s formulation, Reform is much more authentic than Zionism, which as Sand describes, turned EI into an ancient Hungary or Poland, as envisioned by the respective nationalist movements.

I recommend the book – presumably there will be an English edition – particularly for people whose understanding of Jewish history derives from Zionist sources. The nationalist brainwash did not begin with Gideon Sa’ar: as Sand notes, the very word “hellenizer”, or Mityaven, is Zionist in origin. Our main sources for the Hasmonean period, the Makabim books, do not mention the term: they speak only of “sinners” and “breakers of the covenant.” In order to turn the religious sinner into a national sinner, Zionism had to come up with terms which the people of the time would have found meaningless.

Sand further notes an inconvenient fact: once “Eretz Israel” became a Zionist weapon, it cannot contain itself with Israel’s current borders. Our religious nationalists would commit a sin if they would agree to give up God’s promise, which would force them to reach from the Nile to the Euphrates. This is the historical logic of taking EI out of the narrow borders of Jewish law and into the wild, borderless plain of religious nationalism.

Sand’s last chapter deals with a forbidden subject, the Nakba, on whose memorial the original version of this post was written. He examines it through the history of the village of Sheikh Munis (where Tel Aviv University is now located), and shows how its inhabitants were forced into exile through no fault of their own. It is important, then, to read the book today, at a time when the goons in Herzl shirts and MK Michael Ben Ari sing “He’venu Nakba Aleichem” (“We have brought a Nakba upon you)”, showing again how thin the border between the denial of an atrocity and its justification is; when the police prevent the activists of Zochrot from leaving their own building; and when Sand himself receives a death threat, in the form of white powder in the mail.