The deputy IDF chief of staff came under a barrage of criticism for saying trends that prevailed in pre-WWII Europe can be seen in Israel today. But if Israelis took a minute to reflect on his comments, they would realize that they were more solemn than slanderous.

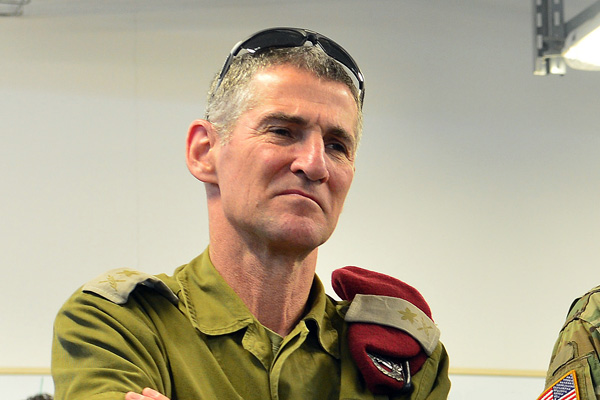

Headlines in Israel are blaring this Holocaust Day over a statement by the Deputy Chief of the General Staff of the IDF, General Yair Golan, comparing trends in Israel to those in Germany leading up to the Holocaust. At the official state ceremony for Holocaust Remembrance Day on Wednesday evening, Golan gave a short speech in which he said, among other things:

“If there’s one thing that scares me about Holocaust memory, it’s identifying revolting trends that took place in Europe in general, and Germany in particular, 70, 80, 90 years ago, and finding evidence of them amongst ourselves, today, in 2016.

After all, there’s nothing easier and simpler than hating the stranger. There’s nothing easier and simpler than fear-mongering and sowing terror. There’s nothing easier and simpler than to become thuggish, morally bankrupt, and self-righteous.” (my translation – the whole speech is here, in Hebrew, courtesy of Haaretz.)

Of course all nuances were destroyed in the media storm that ensued. Many Israelis listening to the news will take away a bastardized version that goes like this: Golan thinks that trends of hatred in Israel mirror the hatred in Germany that led them to commit genocide. By association, what Israel does today is like what Germany did then. Not surprisingly, the IDF and Golan himself issued a statement on Wednesday clarifying that this is not what he meant.

But reactions were swift, angry, and reached partially across political lines. Right-wing Justice Minister Ayelet Shaked told Israel Radio that Golan was “got things completely wrong.” Elazar Stern, a legislator from Yesh Atid and a retired army man as well as a staunch centrist who has sometimes bucked right-wing narratives, allowed that the spirit of the speech might have been legitimate but that the timing was wrong. The Haaretz reporter and analyst Chemi Shalev wrote a post on Twitter before Golan’s comments, and therefore unrelated: “The attempt to draw parallel outlines between the situation of Jews in the Holocaust to Israel’s situation today verges on Holocaust denial and contempt for Zionism together.” (my translation) But as I noted, the one-dimensional headline of the general’s speech will be heard by many in that way and might elicit similar reactions. Education Minister and far-right leader Naftali Bennett tweeted that Holocaust deniers would certainly “put his mistaken words on their flag.”

I can’t say my first concern was whether or not Golan’s statement constitutes Holocaust denial. Nor was my first thought about whether or not I agree that there are comparable trends. I have studied Gordon Allport’s classic texts on prejudice and I believe that a plant or tree metaphor works best: the roots of human nature are shared by cultures and history, but what they bear – fruits or weeds that are edible, salutary, poisonous or lethal – vary. Among those roots, human beings share the capacity for hatred and its seeds grow bitter fruit no matter what the manifestation or degree. So the comparison doesn’t bother me.

Rather, my question was whether as Deputy Chief of Staff of the IDF, Golan can take a step towards de-politicizing the problem of such rage and its manifestation in Israeli society. At present, to name the hatred or to criticize its expressions is to be branded a lefty – an inexcusable and irreparable identity. I am not waiting for all Israelis to embrace liberal, universalist and humanist values that I seek as a guide for my life, because who knows if I’m right? But perhaps we can acknowledge we’ve gone too far in the other direction. Perhaps when the speaker is not a lifelong human rights advocate, an avowed peacenik – a dirty word in Israel these days – but a man of the army, the institution of near-consensus legitimacy among Israeli Jews, people might take notice.

I also saw the statement in light of the recent sense that the security establishment disagrees with political leaders of Israel, regarding the connection between constraints on Palestinian life, and violence. Increasingly, security professionals seem to take frustration of Palestinians into account as a hard security calculation. Perhaps Golan’s statements will also be interpreted as a pragmatic observation, with no political populism driving him. He’s worried about trends that are bad for our livelihood.

This led me to another interpretation of his statement, beyond the pshat, the surface rendering. The text isn’t really saying that Israel might do or is doing terrible things like the Nazis. It isn’t even just about comparing the very incipient stages of intolerance towards the other-du-jour, which he carefully said happened 70 but also 80 and 90 years ago – before the Final Solution was conceived.

Consider the following paragraph:

“The Holocaust, in my opinion, must cause us to search deeply inside the nature of the individual, even when that individual is us ourselves…to wonder deeply about the responsibility of leaders, about the quality of society, [and] it should lead us to thorough thinking about how we – in the here and now – behave to the stranger, the orphan and the widow…The Holocaust should lead us to think about our public life, and more than that, it should lead anyone who is able – not just those who want – to shoulder public responsibility…

On Holocaust Day we would be discussing our ability to uproot the seeds of intolerance, the seeds of violence, the seeds of self-destruction and moral decline…it is an opportunity for soul searching.”

I read him as saying that survival actually means not only physical life or even a sovereign state, but it means being better people: less violent, more responsible, conscious of our conscience, being questioning and self-critical in a way that hateful regimes are not – being anti-triumphalist and unafraid to be circumspect. It means surviving not only death, but rejecting dehumanization of the living.

He longs for an Israel in which people do “personal soul-searching,” on Yom Kippur, as well as “national soul-searching” on Holocaust Day – indeed he says this is our obligation. To whom? I believe he meant that it is our obligation to ourselves, in order to survive. I cannot see this as Holocaust denial. Golan is warning the country to tear out the roots of destruction before they sprout fruit of any kind.

In W. H. Auden’s poem “September 1, 1939” he wrote the following lines:

I and the public know

What all schoolchildren learn

Those to whom evil is done

Do evil in return

Although the poem became famous, Auden hated it and tried to ban it from his collections. Commentaries speculate that he felt the work as a whole was perhaps self-righteous, moralizing and obvious. Or perhaps he worried that the verse above would be seen as justifying the Nazi invasion. One thoughtful critique states:

Is that a reference to Versailles? To Hitler’s personal childhood traumas? …An alternative reading might be that those wronged by Hitler will inevitably strike back later, perpetuating the tragic cycle.

This argument seems intuitive in my mind, if painful. It can cause terrible internal conflict if one actually tries to remember and relive all those lives shattered forever for being Jewish. I don’t see that painful internal conflict as a reason to run away from what might be learned.

Peter Levine, the philosophy professor who authored the critique, goes on to say about that verse: “[T]he broader argument is that people are cruel to each other, and the massive cruelty of Blitzkrieg is just a manifestation of our everyday sin.”

And that, to my mind, is no reason to drop the struggle against such violence, because the instinct to end cruelty and be kind is no less essential to the human spirit. It is part of the meaning of being alive.