For three decades the school at Neve Shalom/Wahat al-Salam has taught our children how to grow and become adults with a cohesive national and human identity, without fear of the other. Today, however, the future looks as uncertain as ever.

(Translated from Hebrew by Rivka Einy)

Atop a small mountain in the Latrun area lies the village we chose to establish a small family. Located between Tel Aviv and Jerusalem, the Arab-Jewish village goes by the name Neve Shalom/Wahat al-Salam.

A few weeks ago, the village hosted an emotional and beautiful event to mark 30 years since the opening of the village school. All of us, parents and children, celebrated in the schoolyard to honor the tremendous effort, and the first of its kind: a school that is both binational and bilingual. With us were also members of the school’s founding generation, the ones who were the first to put Arabs and Jews in the same classroom. Those first classrooms had two teachers, Abed and Eti—one Arab and one Jew.

Back then there wasn’t a set plan—no schedule, curriculum or pedagogical approach. There were no permits that needed to be granted nor any extra supervision, just two brave teachers and the village residents, made up of several families who decided to start the journey together. They believed in their inherent goodness, being good neighbors, speaking two languages, equality, and not being afraid to talk about anything. As for the rest of it, they had no clue what would happen, they simply knew they would figure it out. Every problem has a solution, and those who intend to teach about how to achieve peace there are no shortcuts—they simply need to live together.

Thirty years ago, the HaMishmar newspaper reported that the first ever Arab-Jewish school in the world would open in Neve Shalom, on land donated to its founders by the nearby Latrun monastery. This land did not belong to an expropriated, destroyed Arab village, nor was it state land rife with a painful history. Rather, it was a piece of land free of injustice and guilt, and so atop it we built hope, room by room.

At the whim of the Education Ministry

Today, the school houses approximately 180 students, from kindergarten to sixth grade, in a building located in the heart of the village. During school hours, the main road to the village is closed off in both directions for the sake of the children and their freedom of movement. Until a friend expressed to me how strange it was to close off a main road for eight hours a day, I hadn’t quite grasped just how much the school is prioritized above all else in the village.

Most of the students come from outside the village, from nearby towns such as Abu Gosh, Ein Rafa, Beit Nekofa, Jerusalem, Carmei Yosef, Tzur Hadassa, Kibbutz Gezer, Kfar Oriah, Modi’in, Ramla, Lod, among other places. Thus transportation presents a complicated budgeting and logistical challenge. Sometimes these costs can break the family’s bank, preventing them from continuing to send their children to the school. Unfortunately Israeli citizens lack the right to choose where and how their children will be educated. If as parents you desire different schooling for your children than what you are given, you must pay out of pocket.

Three decades of tireless pedagogical practice sum up the history of the Arab-Jewish conflict rather well. It is enough to walk around the photography exhibition of the school in order to understand that what is happening outside always seeps in—even if we are atop a mountain, somewhat disconnected—the political situation does not bypass us. The schoolchildren hear the army planes on their way to Gaza. Even “price tag” criminals signed our guestbook once. The past 30 years have seen two intifadas, the Oslo accords, a visit by President Clinton, a performance by Pink Floyd’s Roger Waters, attacks, and plenty of ups and downs.

There have been times that the government has recognized and subsidized us, and times when we ran from the Education Ministry, like when former Minister Limor Livnat forced upon us a director who wasn’t really interested in peace, leaving us with no money.

There were good days and dark ones too. Sometimes we spoke of Rabin’s assassination, sometimes we spoke of other ideologically- and politically-motivated murders, such as those of Arafat, Martin Luther King Jr., Mahatma Gandhi, Naji Al-Ali (the famous Palestinian cartoonist), and others.

What do we do on Remembrance Day?

In a country where Israelis and Palestinians live together, work and meet in the supermarket, to be educated together was once considered bordering on the forbidden. Even today relations remain unstable.

When everybody on the outside is talking about peace, we are considered “popular” and “cute,” and the Ministry of Education sends smiley people to take photos of us under our peace arch. When peace goes out of fashion, the very same model of education that emphasizes peace, equality, social justice and democracy is kicked aside in favor of Jewish heritage and Zionism.

Sometimes we are up and sometimes down, but the journey has continued for 30 years based on the belief that there is no other way—and thanks to the donations and volunteer efforts of the sane world abroad. Developing this model comes with many errors and many successes. Debates surrounding what we should discuss and do not were not simple: how do we mark the national holidays of Independence Day and Nakba Day, Land Day and Remembrance Day? You’d be surprised that even in this field there are various fashionable trends, such as the difference between a “narrative” approach and the approach of “managing the conflict,” or whether to separate into various groups during difficult days, or to combine forces, even during times of crisis.

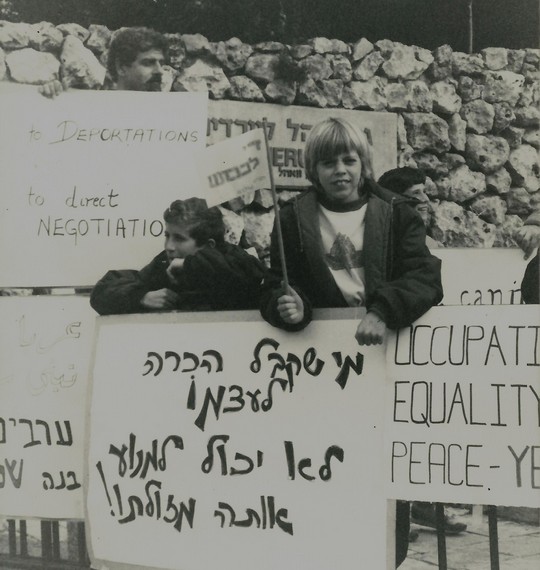

I have learned over the years that we were once more daring. There was a time when our children went to demonstrations and openly opposed the war along with their parents. We used to shout for an end to the occupation and for a peace agreement. We used to see the road more clearly and would go the limit with our young students.

The task now is to survive the military operations, wars and manifestations of hatred and racism. It has become a difficult task in the shadow of governments who do all they can to dispossess, colonize and separate—to govern and embitter the lives of millions of Palestinians and to control them in the name of the Jewish state and its security. We no longer even speak of the peace process, which is miserable and wretched. It seems that soon the message of peace, justice and equality among humans will be denounced as an anti-Semitic, not to mention incitement against the state itself.

‘Have mercy on our children’

Eti Edlund, our founding teacher, now a grandmother to children in the school, was left alone after her co-founder, Abed Islam, passed away a few years ago. “We have met many people on our journey,” she says, “academics who have seen beams of light emanate from our institution, and those who view us as a generation of sinners, who would, heaven forbid, have their children intermarry. We have met senior officials from the Ministry of Education who dismissed the idea with a wave of the hand, only to embrace us after nine years of work. We met so called ‘experts’ who believed that teaching two languages simultaneously would harm the development of our children, as well as good friends who took pity on our own children because we would be their teachers.

“We have heard, learned, changed, and continued forward resolutely, eyes wide open and with a willingness to adopt any idea or piece of advice, any bit of help along the way. The goals we set for ourselves were clear and concrete: to bring together two cultures, teach both languages, and create a school where students enjoy learning.”

During the ceremony I met a mother from Abu Gosh, a graduate of the school whose son is currently in third grade. With tears in her eyes she walked around the exhibit, telling her son how much love, warmth and joy she experienced in the school, and how much she wanted it to continue through high school, rather than end at seventh grade.

Students of a bi-national and bi-lingual school grow to become adults with a cohesive national and human identity, an awareness of their history and that of their neighbors, who are not threatened by the Jewish student on the nearby bench or afraid of a game of hide-and-seek led by an Arab student during recess. They value meaningful learning and know how one can be happy while learning at the same time. And yes—they may even be world’s most naïve people and believe that peace is on its way.

Samah Salaime is a social worker, a director of AWC (Arab Women in the Center) in Lod/Lyd and a graduate of the Mandel Leadership Institute in Jerusalem. This article was first published in Hebrew on Local Call, where she is a blogger. Read it here.