The normalization of relations between Israel and Sudan, publicly announced on Oct. 23, has been on the horizon for several years now. News reports from the past weeks have consistently portrayed the normalization deal as a story about a staunch enemy of Israel abandoning its old ways and turning into a friend. The Khartoum Summit of 1967, in which Arab leaders called for “no peace with Israel, no recognition of Israel, and no negotiation with Israel,” has been repeatedly invoked by commentators to support this narrative.

But the longer history of Israeli-Sudanese engagements is a more complex one — somewhat less transformative, and yet closely linked to the ongoing efforts of both states to manage their position vis-à-vis the Arab world.

Once Iran’s prime African ally and an important hub for weapons transfers to Gaza, Sudan shifted from Iranian to Saudi patronage after the outbreak of the war in Yemen in 2015. Soon thereafter, its leaders began to signal they may be open to relations with Israel as well. After the country’s democratic revolution in 2018-19, which brought to an end three decades of Islamist rule under President Omar al-Bashir, this rapprochement was accelerated.

But the trajectory of this process has been shaped, perhaps more fundamentally, by Sudan’s decade-long financial crisis, which was set in motion when South Sudan gained independence in 2011 and disconnected Khartoum from its most important source of cash at the time: oil. It was this crisis that led Bashir to seek new allies with deep pockets in the Gulf in the following years. It was also this crisis that led to an increase in the price of bread in 2018, sparking protests in urban centers across Sudan that ultimately brought Bashir down.

Since August 2019, Sudan has been ruled by a Sovereignty Council led by army generals, uncomfortably sharing power with a civilian transitional government. What the new leaders inherited was a bankrupt state, whose need for international assistance only increased in recent months due to severe floods in large parts of the country. To gain financial support and open their country to foreign investment, they hoped to finally have Sudan removed from the U.S. list of state sponsors of terrorism, where it was placed in 1993, at the height of Bashir’s rule.

Normalization with Israel, of course, was never a formal requirement for the country to be taken off the American list. But Israel and the United States, as Alex de Waal writes, saw Sudan’s “economic desperation as an opportunity for achieving major political wins at minimal cost.” Leveraging his warm ties with the Trump administration, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu sought to have the Americans buy Sudan’s friendship for Israel. Keen to score another win before the election, U.S President Donald Trump was happy to use the remarkable leverage afforded by the sanctions in order to coerce Sudan into submission.

Establishing ties

Sudan’s political history is often told as a story about a troubled relationship between the state’s political and economic center in Khartoum and the riverain north, and the marginalized, excluded peripheries in the south and west — Darfur, South Kordofan, Blue Nile and what is now independent South Sudan. The history of Israeli involvement in Sudanese affairs may be told as one of shifts between seeking to buy the loyalty and cooperation of rulers in Khartoum and undermining them, most prominently and influentially by supporting their political and military opponents in the south.

When Israel declared independence in 1948, Sudan was ruled by an Anglo-Egyptian government; it was a huge colony, large parts of which hardly integrated into the state, connecting British East Africa, the Red Sea, and the Middle East. A small number of Sudanese combatants joined the Egyptian military during the 1948 war. Since it was under foreign rule, Sudan was not a member of the Arab League, but after the war Egypt immediately sought to persuade Britain to cease all trade between their shared colony and what became the independent state of Israel, in line with the Arab League’s boycott.

In the years leading to Sudan’s independence in 1956, ties were established between Israeli diplomats in London and leaders of the opposition Umma party, who sought to curb Egypt’s influence in Sudan and prevent the unification of the countries. Not much came out of this discreet relationship: Sudan gained independence and was never united with Egypt, as some Israelis may have feared, but it did soon join the Arab League. By the late 1950s, Israel’s efforts to cultivate political alliances in the Global South shifted to newly independent states elsewhere in Africa.

But it was not long before Israel emerged as an obvious ally for another Sudanese opposition group operating not in Khartoum but at the margins of the state. By the early 1960s, southern Sudanese politicians, mostly operating in exile, were openly calling for the independence of the country’s southern provinces, home to numerous African communities that were marginalized and oppressed by the Arab government in Khartoum. With very little funds at their disposal, they soon began to approach Israeli diplomats in Africa, asking for donations, technical assistance, and political support in their battle against the Sudanese government.

These were Black politicians, speaking clearly in the language of pan-Africanism, calling for the liberation of an African people from what they described as Arab colonial oppression. The potential value of the southern cause for Israel’s efforts in Africa was immediately apparent to officials in Jerusalem. When Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser worked to position his country at the center of Afro-Asian anti-colonial solidarity while branding Israel as the ultimate imperial enemy, southern Sudan represented an opportunity for Israel to undo this narrative and portray the Arabs as racist colonialists. If the southern cause gains the world’s attention, an Israeli official suggested at the time, “it may lead to the destruction of Nasser’s status even among peoples and leaders with whom he was able to build close ties, and tarnish his name among many peoples around the world.”

Buying Khartoum’s cooperation

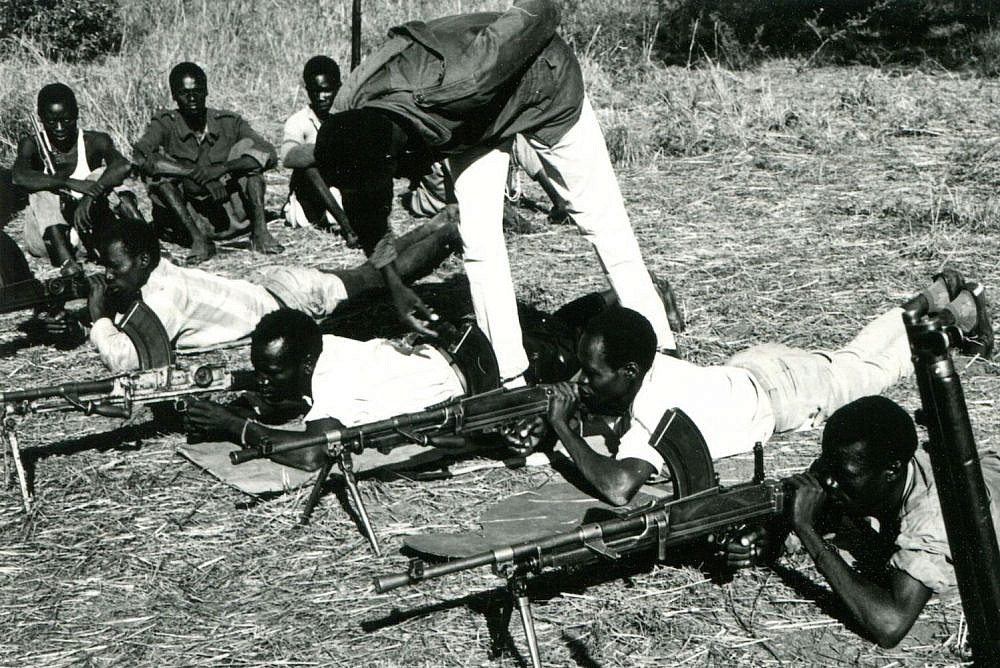

Israel’s military support for the rebels in southern Sudan began after the Six-Day War. Sudanese troops were sent to support the Egyptian military along the Suez Canal. Israeli officials hoped that training and supplying arms would help bolster the military capacity of the Anya-Nya southern guerrilla movement, thus keeping the Sudanese military preoccupied in southern Sudan. Meanwhile, Israel also produced and disseminated propaganda for the rebels, hoping to “draw the attention away from Palestinian propaganda about persecution in the territories and from the Fatah propaganda about an Arab liberation war.”

Sudan’s first civil war ended in 1972 with a peace agreement that granted the south greater autonomy but not independence. Israel’s ties with the southern rebels terminated, but by the end of the decade, the Mossad was back in other parts of Sudan, this time devising ways to smuggle Ethiopian Jews who migrated into the country to Israel. The creative use of a fake diving resort on the Red Sea to carry out this task gained great fame in recent years, becoming the subject of several books and a Netflix film.

But by the mid-1980s, a more convenient way to get this population out of the country emerged: buying Khartoum’s cooperation. President Jaafar Nimeiry, who took power in a military coup in 1969, was in desperate need of funds to “grease the wheels of his patronage machine” in order to stay in power. Israel, by then Washington’s prime Middle Eastern ally in the Cold War, was in a position to offer American money. It was estimated that American Jewish organizations and the U.S. government paid more than $55 million to Sudanese officials in order to carry out Operation Moses, the famous airlift of Ethiopian Jews from Khartoum to Israel in 1984-85, and that “apart from logistical costs, the money was mainly used as bribes.” The cash did not save the regime, however. A few months later, Nimeiry was overthrown.

Under Bashir, Sudan emerged as a regional hub of Islamist activity, maintaining close security cooperation with Iran and supporting members of various Islamist militant groups, including Hamas and Palestinian Islamic Jihad (PIJ). Al-Qaeda leader Osama Bin Laden, still a relatively unknown figure at the time, also lived in Khartoum in the early 1990s. Israel, therefore, was firmly back with Khartoum’s opponents in the region: rifles sold to neighboring Chad in 2006, coincidentally or not, quickly ended up in the hands of Sudanese rebels in Darfur. When South Sudan gained independence in 2011, amid tensions with Sudan, Israel immediately recognized it and sold weapons to its government. On multiple occasions, Israel bombed sites in northern Sudan, targeting weapon convoys and military infrastructure.

Turning tables

In recent years, the tables have turned again. While South Sudan descended into instability due to renewed civil war and largely lost whatever significance it may have once had as a strategic partner in the region, Khartoum re-emerged as a potential ally. In the dying days of his regime, Bashir, somewhat like Nimeiry, hoped that Israel and the United States might help him survive. He was too late. After he was overthrown, and with the support of the United Arab Emirates, the United States and Uganda, normalization between Israel and Sudan suddenly appeared within reach.

Not unexpectedly, however, Israel resorted again to cutting deals with Sudan’s military leaders. In February this year, General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, the head of Sudan’s Sovereignty Council, met with Netanyahu in Uganda. The meeting immediately won Burhan the praise of U.S. Secretary of State Michael Pompeo, but left Sudanese civilians wondering who had given a non-elected general the mandate to negotiate with Israel on their behalf. In August, Pompeo visited Khartoum, promising to remove Sudan from the state sponsors of terrorism list if it recognizes Israel. Negotiations continued in September in Abu Dhabi, but the Sudanese public was largely left in the dark with regard to their progress.

Sudan’s civilian Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok publicly called for the two issues to be separated, arguing that Sudan’s transitional government has no mandate to normalize relations with Israel, and that the matter will have to be decided by a democratically elected government in the future. But it seems that the decision was not entirely his.

Trump’s phone call with Netanyahu, Burhan and Hamdok last Friday, during which normalization between Israel and Sudan was announced, came immediately after his announcement that he is removing Sudan from the terrorism list, making it clear that the two issues were anything but unlinked. Neither Netanyahu nor Trump wanted to wait, since neither of them know where they will be in a few months, while elections in Sudan are not due before 2022.

There is a good reason, therefore, that Sudanese officials have protested that Trump’s pressure on Sudan was undermining the popular legitimacy of its leadership and therefore also the country’s political transition. After the normalization announcement, some citizens took to the streets to protest in Khartoum. Political parties remain divided on the issue, and on whether or not Sudan’s transitional government has the authority to approve an agreement between Israel and Sudan. But the decision to pressure Sudan to normalize ties, it seemed, was based on the estimation that as controversial as the move may be, the Sudanese public will ultimately swallow the bitter pill and the government will be able to push it through.

Netanyahu promised to send Sudan $5 million worth of wheat — a symbolic gesture, given that bread is essential for keeping Sudan’s urban constituencies pacified and its current leadership afloat. Israel’s hasbara machine, as expected, quickly started celebrating the latest addition to Israel’s expanding “circle of peace” in the Middle East. It is safe to say, however, that for many civilians on the other side of the Red Sea, the negotiation of said “peace” is primarily viewed as something between blackmailing and crude bargaining. Behind the ambitious rhetoric about a bright dawn of a new era, it suggested, the way politics are done may not have changed a great deal.