Why would Italian Jews vote for a man who says Mussolini wasn’t all that bad?

By Anna Momigliano

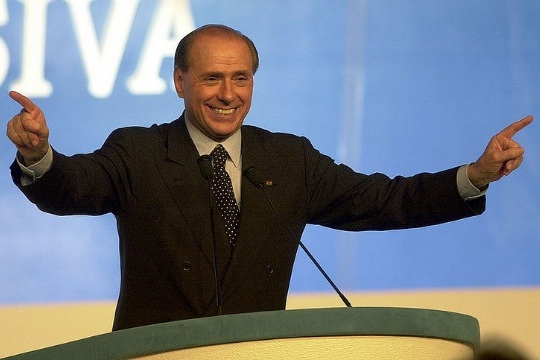

ROME – After dominating Italian politics for two decades, Silvio Berlusconi is running for re-election. Recently, the flamboyant 77-year-old tycoon spoke in praise of Mussolini – incredibly, he made his remarks on Holocaust Remembrance Day, at the January 27 ceremony held in his native Milan.

“The Racial Laws [that stripped Jews of their civil rights in 1938] were the worst sin of a leader who, in other respects, accomplished many positive things,” Berlusconi said. His audience included local Jewish leaders.

Predictably enough, he was booed.

But Berlusconi was not addressing the Jews in the audience.

With a national election scheduled for February 24 and 25, political campaigns are at full throttle in Italy. So it makes some sense that Berlusconi, whose self described “center-right” People of Freedom party is faltering in the polls, is doing his best to please conservative voters who, due to the economic crisis and a series of corruption scandals, are now beginning to question his leadership.

Mussolini is still quite a popular figure in Italy. This is true not only for right-wing radicals, but also for more mainstream conservatives. Italian law defines “apologizing for fascism” as a criminal offense, but it’s quite common to hear positive comments about Il Duce’s regime in private situations. I myself recall odd dinner party conversations on the topic.

According to a 2010 survey, Mussolini is Italy’s second most popular historical figure of all time, second only to Leonardo Da Vinci. The results of the survey are probably exaggerated, given its methodology – it was conducted by volunteers for a well-known history magazine – but it reflects a general climate in which the historical responsibilities of fascism are downplayed.

Berlusconi has made controversial statements about Mussolini before. In 2003 he claimed “Mussolini did not kill anyone.”

In fact, Mussolini did kill quite a few people – including 7,000 Italian Jews sent to Nazi camps with the help of the fascist regime. Click here to view all their names, dutifully collected by historian Lilliana Picciotto. Many of those Italian Jews boarded their trains to Auschwitz at the central station in Milan, where the ceremony was held at the end of last month.

It’s strange enough that Berlusconi was invited to speak at a ceremony memorializing Jews who were murdered with Mussolini’s help. Stranger still, though, is this: Not only do many Italian Jews vote for Berlusconi, but some are actually members of his party.

Currently there are at least two Jewish members of parliament who were elected as candidates for Berlusconi’s party, People of Freedom. For the upcoming election, the party even has a candidate from Israel, 30-year-old Sharon Nizza (the Italian electoral system includes a number of special seats for Italians living abroad).

Mussolini’s own granddaughter, Alessandra, is also a candidate on the People of Freedom’s party list.

In an interview with La Repubblica, Nizza admitted she was embarrassed by Berlusconi’s pro-Mussolini comments. She vowed to “make him change his mind.”

In other words, defending Mussolini is considered embarrassing, yet tolerable – something to be outraged over for a while and then forgive.

Emanuele Fiano, a member of parliament for the left-leaning Democratic Party and son of a Holocaust survivor, was much harsher in his judgement. “I can’t see how a Jew can vote for Berlusconi, after this,” he said.

The truth, however, is that many Italian Jews will continue to vote for Berlusconi, just as they did after he claimed in 2003 that Mussolini “did not kill anybody.”

Jewish support for Berlusconi is based on complex factors. The most obvious is that Italian Jews vote like all the other Italians: some of them vote right, some of them vote left. And in Italy politics is rarely about ideology, identity or civil rights: people tend to vote according to their economic interests. This also explains why Berlusconi’s party is so strong in the North, which is much wealthier, but is also socially more progressive than the South.

Another explanation is that the Right is traditionally more friendly to Israel than the Left. Indeed, Berlusconi used to be one of Benjamin Netanyahu’s few supporters among western leaders, prior to his resignation in 2011. The Italian Left, on the other hand, has a reputation for its “pro-Arab” bias. This was true in the 1980s, when under the socialist government Rome was considered a safe haven for Palestinian groups. But much has changed since then.

To put it simply, some see it this way: “Italian Jews need to chose between those who don’t love Israel and those who don’t love Jews,” wrote demography scholar Sergio Della Pergola in an editorial published by Pagine Ebraiche, Italy’s Jewish newspaper. He was quoting his own daughter.

Personally, I don’t agree with this view. Yes, Italy’s Left is often critical of Israeli policies, but in many cases they have a good point. But even if one does agree with Della Pergola’s daughter, the question remains: how can Italian Jews, whose families were directly affected by the Holocaust, still vote for a party led by a man who says that “Mussolini didn’t kill anyone”? How can they vote for Berlusconi, no matter how pro-Israel he is?

In the U.S. and the U.K., some Jews argue that contemporary Jewish education places too much emphasis on the Holocaust as a foundation for Jewish identity – as opposed to, let’s say, love for Torah or the relationship with Israel.

Sometimes I wonder if in Italy we have the exact opposite problem. And I ask myself how so many of us have come to believe that Israel is more important to us than the fact that our grandparents were slaughtered by a man who, according to Berlusconi, “has done many positive things.”

But then, I forgot: Mussolini didn’t kill anyone, did he?

Anna Momigliano is an Italian journalist focusing on the Middle East and new media. She edits the magazine Studio and authored Karma Kosher, a book about Israeli youth.