This series will soon arrive at Nitzana. Doors open on the left. The next stop is Nablus. This will be the last stop. Thank you for riding with Elisha Baskin and me.

(for the full, four part project, click here)

The country is magnetic. Several energy fields hide in the terrain, emitting the land’s intensity and mystery like orbs in a Tesla experiment. One such field is famously Jerusalem, another, far vaster one, is the desert.

A journey that began in a dusty ditch on a city’s outskirts, now furthers into the wilderness. Elisha and I take a bus from Be’er Sheva into the Negev. The Turkish wartime rails extended south of here, and the remains of a station await us at Nitzana, directly on the Egyptian border.

Nitzana, a Nabatean town, has not been a place of proper human habitat since the ninth century. A train station was built there in 1915, and was literally nowhere-central. It served a remote police station that guarded the empire’s border with the British controlled Sinai, and a hastily constructed hospital where war wounds were tended. The hospital’s ruins can still be seen atop the mound of the ancient town. It seems like a very bad spot to bring potential amputees. Go figure.

History moved quickly. A flood of Union Jack-waving Aussies and Kiwis appeared from the southern wilds and ousted the Turks from the holy land after centuries of dominance. Nitzana station began crumbling almost as soon as it was built. When we arrive there today only the limestone water tower is left to remind us of long lost wars. It sticks out of the wasteland in majestic mystery, much like Arthur C. Clark’s monolith. We wander over the expanse, finding a few more walls, recognizing traces left by the rails, taking in the silence.

Following the buzz of music and children’s voices at Be’er Sheva, silence seems to be telling a truth about history. We need to listen well, and not limit ourselves to a tower and a wall. We haven’t yet answered this project’s principle question: why are we even doing it? What’s in a station?

We climb the mound, or “tel.” A dry wind blows through the dead hospital’s windows. We are the only ones here. The Nabataeans are gone, the Turks are gone, the trains are definitely gone. Looking east, we try to spot the Holot internment facility, where Israel keeps thousands of African Asylum seekers imprisoned without trial, hoping to deter others from seeking refuge on these shores. It is hidden by the desert’s ripples.

Not a city to pass by

One more station is left on our list, and it’s role in the country’s history is largely un-train related.

It is Mas’udiyya station, mistakenly known as Sabastiya station. In 1915, the Ottomans decided to lay an arm of rails between Afula and Jerusalem, one that would link Damascus to Al Aqsa via the hill country. This arm reached down to the Nablus area. Mas’udiyyah got a station, and Sabastiya, a nearby historical hill town, became accessible to all. Then war reached the region and construction on the line was abandoned in favor of the ill-fated desert line.

Sixty years later, the area became part of the Israeli-held West Bank. Soon afterwards, Jewish activists attempted to form settlements. At first Israel’s government removed all settlers from the occupied territories and forbade them from establishing permanent footholds. Many of the confrontations took place at Mas’udiyyah’s station. No fewer than seven times did activists return to the station and held sit-ins. They were drawn to the structure due to its proximity to the ruins of Biblical Shomron and the fact it was state property.

On the eighth attempt, one cold day in December of 1975, the settlers received fond news: Shimon Peres, then minister of defense, granted them the right to settle nearby, at what became the settlement of Kedumim. One day after our desert escape, Elisha and I head across the lines, to see the source of so much complexity.

The road to Mas’udiyyah, however, goes through an energy field and we get trapped. It is Nablus, a city you can’t just cruise through. It bewitches the senses and particularly the tongue.

- Like crazy, we do.

We stop to enjoy heavenly knafe, to buy sesame halva, black-seed halva, pumpkin jam and dates. We chat with the owner of a natural remedy shop about his university days in Rome. We sip good coffee in a shisha shop equipped with a dusty boombox and adorned by images of Jordanian royalty. Elisha, who missed her calling as interior designer, gawks and gapes and clicks her shutter repeatedly.

Lower your expectations

It is here, among the sweet billows, Lebanese music and chatter of card players, that we begin wondering whether Nablus itself once sported a railway station. The Mas’udiyyah arm must have reached down to here. Did it indeed? And has anything remained? We contact Husam Jubran, who guides with me on the National Geographic Holy Land tours. He is not sure, and reaches out to a Nablusi friend, who says yes. A station once was here. She gives us its location and urges us to lower expectations.

We find it, on an eastern edge of downtown. This area is still a transport hub. Yellow “service” minibuses park in a nearby lot and their drivers direct us to the right spot: a one story building, its tiled roof crumbling. Some sort of a factory is operating inside. We ask permission to enter and find ourselves on a platform, beneath wooden beams that held an Ottoman awning in Ottoman days. This once was, without any doubt, the station. Today it is, without any question, a pickle factory.

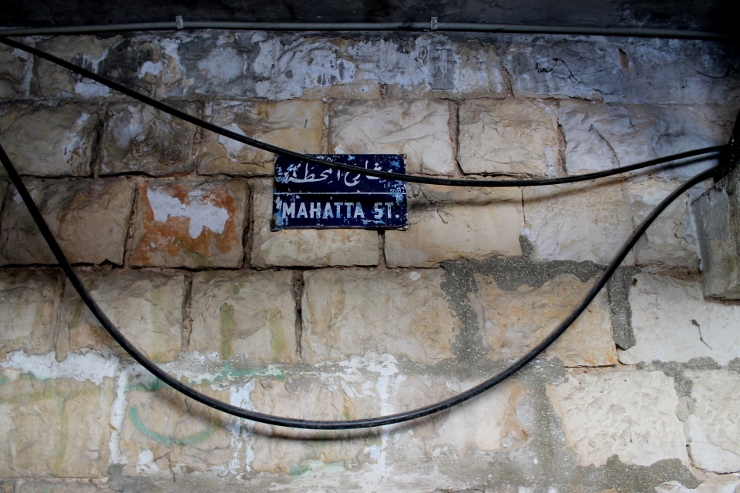

We receive a gift jar of pickles, and are taken to see an old street sign that still hangs on an outside wall. Faisal Street was once Station Street. Aside for this business, the building houses a store for household utensils and a hotdog stand. We are enchanted. This station isn’t abandoned, it isn’t reused, it isn’t destroyed. It’s a hotdog stand with a limitless supplies of relish. Brilliant.

A passerby notices our joy and stops to chat. He points to a traffic island full of wild growing bushes and trees, and says: “There’s more of the station there.” We circle the patch of greenery and find a limestone water tower. It is crowned with a huge billboard advertising a bank. All about this ad, Nablus honks its many horns, beneath it is a tower identical to that one that stood in silence in the desert yesterday. That still stands there this moment.

Really that far?

Could that desert and this city truly exist simultaneously, in the same land? Two towers remind us that they do. The environments that make up our country differ so much, the mental barriers are taller than the physical ones. Nitzana’s tower is situated across the separation barrier from here and in an entirely different climate, its nearest neighbors speak a different language, write in a different script, would never dream of coming here, but is it all really that far?

How easy was it to get to Nitzana in 1915? You would travel north to Afula, than to Haifa, then to Jaffa, then further south, or just go through Jerusalem and Hebron by a horse-drawn dolmush. Today, approximately 95 percent of Nablus residents do not possess permits to enter Israel. Access denied.

We have split this place up so that only a search for something random can help us piece it together. What we were looking for is home. Our land, which once could be reached by train from Europe and Africa, has been cut off the network, then smashed like a plate. We have been piecing together it station by station. Now we have it in our hands. We have made a new connection. We can move on to other journeys. How about a spin on the Trans-Siberian?