Israel’s top satire program takes on the Nakba. Sometimes humor can succeed in places where activism or advocacy fall short.

The tortured road of the Nakba towards a legitimate place in the Israeli historical memory has some unexpected twists.

Eitan Bronstein Aparicio and Dr. Eléonore Merza Bronstein recently explained that at first, it was mainly Palestinians who wished to commemorate the Nakba. Next came far-left wing Jews in Israel. Following that came the right-wing or oppositional Jewish Israeli approaches, such as “Jewish Nakba,” a phrase coined over the years as a name for the violent expulsion of Jews from Arab countries following the establishment of the State of Israel. Their piece highlights how defensive efforts to reject the history of the Palestinian Nakba, or turn Jewish history into a political rebuttal, actually acknowledge its importance. The first of these was the childish but notorious “Nakba – Bullshit” campaign by the bully-group Im Tirzu.

However, the recent appearance of the Nakba in popular, mainstream Israeli culture may be the most surprising roadstop of all.

With little blowback or social media shrieks, Israeli television viewers of all ilk were treated to a surprisingly detailed, historically informed re-enaction of the very Nakba most would prefer to ignore. This happened on Channel 2, the highest-rated, mainstream channel in the country. And not only on Channel 2, but on Eretz Nehederet, the most beloved, top-ranking satire show in the land. And that would have been enough, but the show went further, broadcasting the practically subversive skit in its Independence Day episode. Had Channel 2 been a public company, it would have violated the Nakba Law, which stipulates that a public organization observing the Nakba on Independence Day can lose its public funding.

But perhaps what can’t be done through activism or advocacy can be accomplished by humor. When we laugh, we forgo the pain and think about the content of what made us laugh. Maybe that way we forget to be shocked at the choice of content to begin with.

It’s hard for an un-funny writer to re-create humor through description, especially in translation. It’s even harder when the text is so zippy and quippy, slapping silly jokes and gravitas together like candy-coated medicine.

You can watch the episode here (Eretz Nehederet, Season 12, episode 11, starting around 35 minutes). Otherwise, several highlights stand out that make it so valuable:

Eyal Kitzis – the longtime anchor often dubbed Israel’s Jon Stewart – observes that in recent years, each Independence Day sparks a battle of narratives. This sentence alone would have been inconceivable in a political climate when one’s own history was simply true and there was no such thing as a competing version. The writers of the show are well aware that their audiences are familiar with the problem.

The re-enactment is a flashback to a scene using 1940s versions of well-known characters from the current season: A female Arab pharmacist-poet from the present is now doling out plant-based remedies for malaria to a man in her village, while discreetly inquiring if he has had “unprotected contact with a mosquito.” The hawker who sells awful homemade soups at the shopping mall in the present, and who is in love with the pharmacist, is now the company cook for a Palmach battalion. He fills canteens with soup and rock-hard meatballs solid enough to stop a speeding bullet.

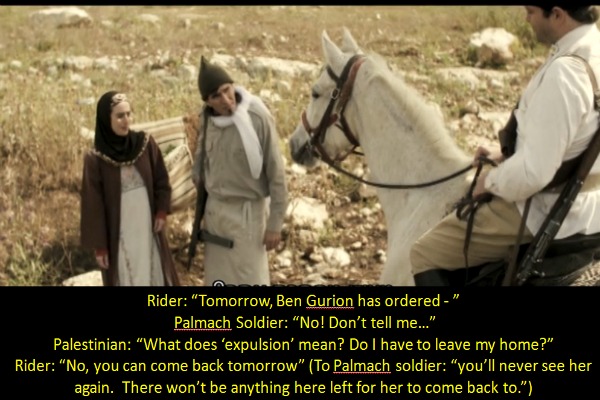

The Palmach shlemiel wanders over to the village and happens upon the pharmacist, collecting plants. They flirt, and as they lean in for an illicit kiss, a mercenary Jewish soldier gallops over to warn them both: She must leave the village ahead of conquering Jewish forces, and the Palmachnik must not waste his time falling in love with her.

The Palestinian woman is shocked that she must leave her home; the mercenary soldier lies and tells her she can return the next day. On the side, he tries to tell the Palmach soldier about the plan to expel the villagers, by order of Ben Gurion. But the Palmach soldier cuts him off and insists that he not spoil the ending. Mocking modern day addictions to TV series, the Palmach soldier explains that he’s only up to the UN partition vote (“Argentina said ‘sustains’” – Israelis love poking fun at their own poor English).

There is no dancing around the issue, no skirting the margins; the skit is the nexus of the Nakba itself. By taking a sly position on the huge historical debate over Ben Gurion’s knowledge or guidance of efforts to remove as many Palestinians as possible under the cover of war, the writers implicate everyone, from lowly soldiers who prefer not to know, and the top who probably does.

The scene, not even three minutes long, also takes place on the very battleground of memory. It is composed of information made available only through exhaustive efforts of historians over decades of research, involving lawsuits against the Israeli government to declassify files and archives. Even still, some of these archives have since been re-classified. Along with the history that increasingly cannot be disputed, there is also little question that the state exerted considerable effort, and still does, to suppress the events. With this episode, Eretz Nehederet has jumped into the ring, on the challenger side.

Typically, Eretz Nehederet has the last word, and it borders on cynicism. The flashback returns to modern-day Israel, where the the village has morphed back into the shopping mall and two woman are wrestling on the ground over a shirt (this actually happened, when H&M opened its doors in Tel Aviv a few years ago).

Cheap shots, to be sure. But if even one or two average viewers – not political activists, not left-wingers and not Im Tirzu types – are left questioning if the present justifies the past, or questioning anything at all, we might do a better job of redressing both.