Israel refuses to come clean about its links with the murderous Hutu regime that carried out the genocide in Rwanda 25 years ago. But Foreign Ministry documents show that Israel was aware of the massacres against the Tutsi minority way back in the 1960s — and turned a blind eye.

By Eitay Mack

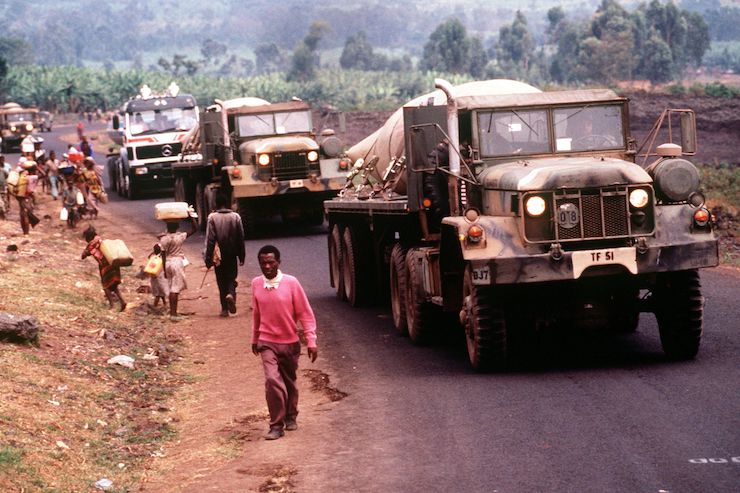

On April 6, 1994, hours after a surface-to-air missile shot down a plane carrying the dictators of Rwanda and Burundi, the ruling Hutu regime of Rwanda began carrying out a well-planned genocide against the Tutsi minority. In 100 days, 800,000 Tutsis were murdered, as were moderate Hutus who opposed the mass killings. It is considered one of the largest genocides since the Second World War. Over the past few months, Rwandans have marked 25 years since the genocide.

Despite repeated requests, Israel has continually refused to reveal its ties with the regime that carried out the killings, despite various reports that claim the Israeli government provided military support to the Hutu regime during the Rwandan Civil War that raged until 1994. According to those reports, Israel continued sending weapons — including guns, ammunition, and grenades — to the Hutus as the genocide was taking place.

Yet despite Israel’s refusal to reveal its ties with the regime throughout the 90s, documents published below (which can be read in Hebrew here and here) reveal that throughout the 1960s and into the 70s, Israel was well aware of the severity of the crisis in Rwanda, as well as the danger of bloodletting in the country. Still, it reportedly continued to support the dictatorship.

The colonial roots of genocide

The roots of the Rwandan genocide go back to the days of colonial rule in the 19th century. Until then, there was no rigid distinction between the Tutsi and Hutu ethnic groups. The Germans, who formalized their rule over Rwanda in the Berlin Conference of 1884, established their colonial regime based on a feudal monarchy run by an elite of the Tutsi minority, creating a racialized hierarchy between them and the Hutu.

The Belgians, who took over Rwanda during the First World War, entrenched those racial distinctions, including Tutsi supremacy and the oppression and exploitation of the Hutu majority. Beginning in 1935, the Belgians began forcing Rwandans to carry national ID cards that listed their ethnic classification, thus blocking the possibility of “passing” between the two groups.

In the final years of their rule, the Belgians switched sides and began supporting the Hutus, after the latter revolted against the Tutsi regime in 1959. The racial hierarchy flipped and the Hutu elite began oppressing the Tutsi. After Rwanda won its independence in 1962, that same Hutu elite continued with its policies of racial oppression with the support of Belgium.

The newly-independent Rwandan state was led by Grégoire Kayibanda, a member of the Hutu elite. He ruled the country with an iron fist until he was overthrown in a military coup in 1973 and was replaced by his defense minister, Juvénal Habyarimana. Habyarimana led the country until his assassination in the 1994 plane incident.

Like the colonial regime before them, Kayibanda and Habyarimana maintained an ethnic dictatorship, forcing Rwandan citizens to carry the same ID cards. Those cards dictated the fate of every citizen, including their chances of getting accepted to a university, working in the civil service, or opening a business. Massacres and pogroms against the Tutsi continued under Kayibanda and Habyarimana.

Over the years, hundreds of thousands of Tutsi fled the country. In October 1990, the Rwandan Patriotic Front, led by Tutsi refugees, invaded the country from Uganda, leading to the beginning of the civil war. There is ample documentation of massacres against the Tutsi across Rwanda during the civil war, including by the Hutu regime’s death squads.

Things reached a fever pitch with the downing of Habyarimana’s plane in 1994. Radio Télévision Libre Des Mille Collines (Thousand Hills Free Radio and Television) broadcasted continual calls for exterminating the Tutsi, including by reading names, addresses, and license plates of Tutsis and moderate Hutus. Some of the commands to carry out the extermination were broadcasted on the station, and the murderers often carried a transistor radio along with their weapons. The Tutsis were deemed “cockroaches” that must be eradicated.

And though the genocide was planned by the dictatorship in Rwanda, with its well-trained death squad militias, it was also perpetrated by average citizens: husbands murdered their wives, wives murdered their husbands, neighbors murdered one another. The majority of the killings were carried out with machetes, as well as rifles and sub-machine guns.

Penetrating the security establishment

A look through the files of the Israeli Defense Ministry — which can be found at the National Archives and were recently opened to the public — reveals that during the Kayibanda dictatorship between 1963-1973, Israel was involved in building up the Rwandan security forces, and sought to benefit politically from the ethnic divisions there.

Missives sent by Israeli representatives in Rwanda show that they knew full well about the activities of the dictator and the army. In a letter sent by Meir Yaffe from Kigali on June 18, 1968, he wrote “It is possible that it is too early to predict that Rwanda is marching toward a military dictatorship, although recently I have been hearing speculations from various circles. Thus, it is a good thing that we are penetrating the security establishment (security services, youth affairs, a visit to Israel by a group of military officers, a visit by the Minister of Defense in Israel, procurement proposals), even if it casts thy bread upon the waters.”

In a missive sent on December 2, 1968, Yaffe asked to receive a report from a Rwandan military officer who led an attempted military coup. According to the letter, the officer visited Israel three months before with with a group of other Rwandan military officers and liked what he saw. “During their brief visit, they learned a lot more than during their two-month training in Belgium,” Yaffe wrote.

In a letter from February 3, 1969, Yaffe described the “Democracy Day” celebrations that took place just a few days earlier. President Kayibanda, wrote Yaffe, delivered a speech in French intended for foreign diplomats, before giving a speech in the local language, which lasted five times as long and described the purges he had carried out in the ruling party.

Lou Kedar, who headed the Israeli Foreign Ministry’s Africa Division, responded with a letter on February 12. “The Rwandan president’s thinking is very strange to me: he curses and insults a number of people who were deputies in his party in a crude and harsh manner, while at the same time advises them to form their own party. It is possible that the term ‘democracy,’ in his eyes, is a broad one.”

Haim Harari, an Israeli diplomat in Kigali, described in a missive from August 11, 1969, an event to inaugurate the new house for the dictator’s ruling party, which included marches by schoolchildren and party activists, and where “most of the songs were about Kayibanda and his party, a veritable cult of personality.” In another letter from the same day, Harari wrote that “We live in a very strange situation in Rwanda, there is not a single daily or weekly newspaper, and if something does happen, the local radio station broadcasts in French and ignores local news stories.”

In a missive from September 26, 1969, Harari explained that because 90 percent of the population are illiterate, during the previous elections voters would approach a representative of the regime waiting near the ballot for assistance, invariably affecting the outcome of the vote. As for the upcoming elections, the country had decided on a different and “original” method of voting, according to which every voter will receive an envelope with the names of the candidates on the day before Election Day. The voter takes the envelope home where he or she is helped by a family member who knows how to read. The following day they are to go to the polling booth with the sealed envelope after marking their choice. In a letter from October 6, 1969, Harari updated that Kayibanda had won an additional term with the support of 99 percent of voters.

None of these things, however, prevented Israel from aiding the regime from marketing itself. On January 10, 1969, Yaffe wrote that he helped the regime prepare a propaganda pamphlet to encourage tourism to Rwanda, with the Rwandan foreign minister asking him to print an additional 10,000 copies.

The Israelis knew

Hundreds of thousands of Tutsi fled Rwanda during that period, following a series of massacres. In December 1963, in response to guerilla attacks by Tutsi refugees in Burundi, the Rwandan regime murdered 10,000 Tutsi citizens within the span of four day. The Hutu regime used the guerilla violence to justify its oppression of the Tutsi who remained in Rwanda (approximately 10 percent of the population), and to label them foreign invaders unworthy of human and civil rights, and who can be raped, tortured, and murdered.

The Israeli representatives knew about the persecution, expulsion, and extermination of the Tutsi. On May 8, 1962, Hanan Bar On, an advisor at the Israeli Embassy in Washington D.C., wrote a letter in which he said that the situation in Rwanda worried the U.S. State Department, perhaps more than any other issue in Africa. Belgium’s departure, he wrote, left “no opportunity for the United Nations to take it upon itself the mission of keeping the peace in Rwanda-Burundi, and that there is no one who would be able to fill the vacuum, which could bring about a civil war.”

In a letter dated July 10, 1962, Israeli Ambassador to the UN Michael Comay praised the UN decision to send a delegation to Rwanda and Burundi in order to oversee Belgian forces there and the training of the local police officers. “Everyone knew that without them there was a serious danger of tribal war and bloodshed following independence, mainly in Rwanda.”

In a missive from November 29, 1968, Harari described contacts between the Rwandan dictatorship’s security forces and forces in Burundi, which sought to work together against Tutsi refugees guerilla groups. “The Tutsi were exterminated by the ‘Hutu,’ which rule Rwanda,” Harari wrote in a letter dated August 25, 1969. A month later, on September 29, Harari wrote that Rwandan army units were stationed on the border with Congo, Burundi, and Uganda “out of fear of an invasion by the Tutsi refugees, known in Kinyarwanda (the local language – E.M.) as ‘Inyenzi,’ or cockroaches.”

In a review prepared by Harari on October 8, 1971, he wrote that “the regime in Rwanda is one of the most stable regimes in the African continent due to the unity of language and the lack of tribal disputes, apart from the Tutsi tribe, defeated by the overwhelming majority of the Hutu tribe, which make up 90 percent of the population… With the elimination of the Tutsi regime in Rwanda in 1959 and their flight to neighboring countries, this factor has not ceased to bother Rwandan rulers to this day. They see this as a potential threat to their regime and this factor must be considered in order to correctly assess Rwanda’s policy toward its neighbors.”

A joint war on refugees

Instead of worrying about the fate of the Tutsi refugees who fled their country, Israeli leaders thought it wise to take advantage of Rwanda’s fear of refugees in order to push the government in Kigali to support Israel in international forums on the issue of Palestinian refugees. “Rwanda has no logical reason not to support our position,” wrote Aryeh Levin, an Israeli diplomat in Kigali, on February 21, 1966. “They understand the refugee problem since tens of thousands of Tutsis are sitting across the border, and it is well known that they are supported by the Arabs (There are Tutsi offices in Cairo, Algiers, and Rabat). Over the last few months, Rwanda has once again been under threat of invasion by Tutsi refugees, some of whom took part in rebellions in Congo.”

On June 8, 1966, the Israeli ambassador to Rwanda described a conversation he had with Rwanda’s foreign minister. In order to deal with the problem of Tutsi guerillas, the ambassador suggested an intelligence course that the Mossad “would be interested in offering the Rwandans.”

In a letter from October 9, 1966, Levin describes a conversation with a Rwandan diplomat to the UN in the run-up to hearings at the UN General Assembly. “I reminded him that in the past year we were disappointed with Rwanda and hope that this time they will be able to demonstrate understanding and friendliness. The fundamental positions of Rwanda and Israel are very similar, especially with regard to the refugee problem. Problems such as the PLO, appointing the Custodian of Absentee Property, among other things, ought to be understood by Rwanda, perhaps more than other countries.”

According to Levin, a representative of Rwanda in the UN responded that “Rwanda will not always be able to go with us on ‘the razor’s edge’: our problems are extremely complicated, and we demand from our friends to understand the nuances of our argument — something that is not always possible. What more, staunch allies of Israel such as the United States, France, and Italy, as well as most of the Africans, have abandoned us.” In response, Levin told him that “Many African countries with a lesser understanding of the refugee problem than Rwanda’s vote for us.”

In a letter from October 21, 1966, Levin says that he met with Kayibanda, to whom he explained Israel’s position vis-à-vis the refugee issue and told him “We expect understanding and cooperation from our friends, especially from those to whom this issue is not foreign.” Kayibanda expressed his support for Israel’s stance on the refugee issue and said that international support for refugees must be prevented, since it is an “opening for intervention in your internal affairs.” Kayibanda asked Levin to send a letter to the Rwandan Foreign Ministry detailing Israel’s demands on various votes and promising that “they will try to act according to our requests.”

Despite the fact that Israel used the Rwandan government’s fear of Tutsi refugees to gain support in its position against the Palestinians, Israeli representatives assumed that Tutsi refugees did not constitute a real threat to Kayibanda’s regime. “The Rwandans know that over half a million Rwandans currently live in Uganda today, among them 150,000 Tutsi refugees waiting for the opportunity to return to their homeland to get rid of the Hutu regime, which is headed by President Kayibanda,” wrote Harari on July 5, 1971. “It is hard to believe that such a step would be carried out, but the Rwandans, who are already naturally suspicious and fear the Tutsis living among them, who are viewed as a fifth column, are anxious about the danger coming from the north.”

Mossad training and Nahal bases

The letters show that the dictatorship in Rwanda hoped Israel would help it with its relations with its neighbors — Congo and Uganda — since the Jewish state had provided military support to those regimes as well. According to a missive by Yaffe from November 15, 1968, the director of Rwanda’s Foreign Ministry had asked for help vis-à-vis the Mobutu regime in Congo, considering “Israel has very good relations with Kinshasa, and since we provide extensive technical and security assistance there, and it is known that Mobutu supports Israel.”

Rwanda also asked for Israel’s support to act as a mediator with Ugandan President Idi Amin after he closed the border with Rwanda. Israel was providing Amin with military support at the time, and according to documents from September 1971, Rwanda and Belgium suspected that Israeli experts were aiding the Ugandan armed forces in their hostilities against Rwanda. Following Rwanda’s request, both the head of the Africa Division in Israel’s Foreign Ministry as well as a representative from the Mossad conferred with Amin on the matter, trying to convince him to open the border. The efforts bore fruit and in October 1971 Israel was able to convince Amin to re-establish ties with Rwanda.

But the ties weren’t solely political. A letter sent by Israel’s ambassador to Uganda on August 11, 1967 claims that Rwandan Defense Minister Juvénal Habyarimana — who would go on to become the leader of the country until his assassination in the plane attack — sent an official request for Israeli security assistance.

The ambassador wrote that “In order to examine this issue in particular, Col. Bar-Saber traveled to Rwanda and took part in a conversation with the defense minister. To summarize, I would like to point out two issues that seem to be worth mentioning: the first relates to the defense minister’s request to send him an advisor who will advise them on the establishment of a security service and will be able to establish basic courses; the second is related to the Nahal (Fighting Pioneer Youth, a paramilitary IDF program that combines military service with the establishment of agricultural settlements across Israel – E.M.).” The documents show that Israel fulfilled its obligations, aided in establishing a new security service, as well as in creating a Nahal-style youth movement.

Israel’s ambassador to Uganda wrote in February 1968 about his conversation with Rwanda’s foreign minister in Kigali. The two agreed that the Mossad would provide a security course that year. “In the beginning of May, two Mossad agents will arrive to lead a basic security course for the security brass, including the head of the [intelligence] service over two-three months,” wrote Yaffe in April of that year. “The minister of defense and head of the security services repeatedly said they would be happy had the Mossad left an advisor to the security head for a period of a year or two. Of course, personally I would recommend doing so with all my heart, since this position allows us to penetrate and influence the nerve center of the state. I hope that the Rwandan defense minister, as well as the delegation of Rwandan officers on their visit to Israel, will deepen their willingness to cooperate with Israel.”

According to a letter sent by the Israeli ambassador to Uganda on July 24, 1968: “The Mossad finished a basic course in Rwanda, and the [intelligence] services are organizing themselves according to the format in which they were instructed by the two Israelis who were with them. I know from the instructors and Meir Yaffe that the Rwandans will ask for a permanent advisor to their security services. It is unlikely that anyone in the Mossad is available for this position, but when considering the circumstances and pressures, they may comply with the request, even for a period of six months.” According to another missive by the ambassador from August 5, 1968, “the head of the Rwandan security services sincerely thanked me for the aid supplied to him and his country by the two instructors who, according to him, did an excellent job.”

In December of that year, Yaffe reported on the continued contacts with Defense Minister Habyarimana. “In a conversation with him on December 12, 1968, the defense minister said that due to the change (in the head of the intelligence services – E.M.), he has asked to wait two to three months before beginning to implement the service’s plan, as was proposed by two of our men (Yehuda Gil and Meir Ben-Ami). He expressed interested in having Mr. Binyamin Rotem visit Rwanda once again… in order to establish ties with the new head of the service and to discuss the proposed plan. I accede to his request.”

The dictator’s love

The Nahal plan went off without a hitch. On June 9, 1971, Harari described how the Israeli Defense Ministry sent IDF officers to establish a Nahal-style youth movement in various camps across the country. A year earlier, on August 6, 1970, he wrote that Israel had submitted reports to the Rwandan defense minister on the progress of the Nahal project, despite the fact that in September 1968, in a letter to Maj. Menachem Baram, Harari wrote that the Nahal training activity had suspiciously moved from the border areas to a military camp near the capital Kigali.

But this was not simply about training Rwandan army officers in Israel, training by the Israeli Mossad, and building a Nahal movement in Rwanda. On June 14, 1968, Director of the African Division of the Israeli Foreign Ministry Hanan Bar-On wrote that the Hutu regime had asked to purchase mortars and ammunition from Israel, as well as to bring Israeli artillery instructors to Rwanda.

It seemed that Israel’s efforts in the country succeeded, and according to a letter from Harari on September 1, 1969, Kayibanda showed “sympathy and admiration for Israel.”

“Rwanda’s position on Israel continues to be sympathetic,” Harari wrote in a letter a year later, “and it will likely support our policy on the Israeli-Arab issue and on the refugee question.” In August 10, 1971, Harari wrote that he proposed to the Rwandan foreign minister to open an embassy in Jerusalem, although this never came to fruition.

In an overview prepared on October 8, 1971, a year and a half before the military coup that overthrew Kayibanda, Harari correctly predicted that the only person who could replace the dictator was his defense minister, Habyarimana. The newly-released documents, however, provide no answer to the question of Israel’s ties with Habyarimana’s regime until the genocide. These documents have yet to be released.

What was Israel’s role in the genocide?

Recent years have seen a number of legal proceedings in Israel, alongside genocide researcher Prof. Yair Oron, demanding the Defense Ministry’s documents on defense exports in the 1990s to the Hutu regime be exposed. Those same proceedings have sought to prosecute Israelis complicit in genocide and crimes against humanity.

In response, Attorney General Shai Nitzan replied that Director General of the Defense Ministry David Ivri ordered the freezing of Israeli security activity in Rwanda on April 12, 1994, six days after the beginning of the extermination of the Tutsi, claiming that only then did he receive information about the outbreak of the civil war. Nitzan claimed that the materials presented to him by the Defense Ministry did not indicate that any Israeli officials were aware of the murderous violence being carried out against the Tutsi before that date.

The documents published here for the first time regarding the 1960s and early 1970s confirm that Israel and its representatives knew for decades about the murderous, racist, and corrupt character of the Hutu regime in Rwanda. Apparently, this did not interest them. Perhaps they had more important interests to tend to, such as securing votes in international forums.

Although the Supreme Court has banned the publication of documents from the time of the genocide in Rwanda (on the grounds that doing so will harm Israel’s security and foreign relations), there is no doubt that public awareness of Israel’s shameful involvement in Rwanda has increased considerably in recent years. The full details of that involvement are still unknown, since some Foreign Ministry documents — as well as all related documents belonging to the Defense Ministry, the IDF, the Mossad and the Shin Bet — are still hidden from the public. There is no doubt, however, that involvement was ongoing.

France’s President Emmanuel Macron recently ordered the appointment of a team of experts and historians to examine his country’s involvement in the events in Rwanda. Twenty-five years after the genocide, it is time for a similar commission of inquiry to be set up in Israel as well.

Eitay Mack is an Israeli human rights lawyer working to stop Israeli military aid to regimes that commit war crimes and crimes against humanity. This article was first published in Hebrew on Local Call. Read it here.