“Catch-67: The Left, the Right, and the Legacy of the Six-Day War,” by Micha Goodman, translated by Eylon Levy, Yale University Press, 2018, 264 pages.

When Israeli pop-philosopher Micah Goodman’s book Catch-67 first appeared in Hebrew, it became a national bestseller. It was published, intentionally, at an opportune moment: Israel was set to mark 50 years since its victory in the Six Day War — and 50 years since the start of the occupation. Goodman wrote that he hoped his book would help Israelis not only begin to move beyond the impasse with the Palestinians, but also begin to heal the polarization caused by that impasse within their own society. “The jubilee year of the Six-Day War is an opportunity for Israelis to reset their internal argument,” Goodman wrote, “and create their discourse anew.”

To help them do so, Goodman sets out to explain in Catch-67 how both the Israeli left and right are correct in their respective concerns regarding the occupation’s future, in important yet different ways. The left, he says, is correct to argue that indefinite military rule over a large Palestinian population in “Judea and Samaria” (Goodman uses the Biblical term for the West Bank) threatens Israel’s Jewish majority — and its democratic character — while the right is correct that withdrawing from the occupied territories threatens Israel’s security.

“The action that lifts one catastrophic peril merely converts into another peril, no less catastrophic,” Goodman writes. “This is Israel’s ‘Catch 67.’” (Never mind that many Israelis, including former Prime Minister Ehud Barak, dispute the claim that withdrawing from the West Bank would jeopardize Israel’s security.)

Released in English in 2018, Catch-67 garnered considerably less attention in the United States, but it is worth paying attention to. While there is much in the book that ought to be dismissed — for instance, Goodman’s dubious claim that Israel does not occupy the land of the West Bank, only its people — it offers a window into the world of the Israeli “center,” a rising political camp perhaps best represented today by Benny Gantz’s Blue and White party.

Goodman’s centrism drapes territorial-maximalist positions in the language of pragmatism, posturing as humanist while disregarding international law and its consensus on what human rights entail. With the end of the Netanyahu era appearing on the horizon, it is this kind of center-right politics that is most likely to supplant “Bibism” as the country’s dominant political ideology, not the radical settler-right that has dominated headlines over the past decade.

In this sense, Catch-67 is an exemplary text of a political tendency that will only become more significant in the coming months and years. Instead of the two-state solution preferred by Israeli doves, or the one-state preferred by Greater Israel messianists, Goodman proposes a different, “pragmatic” approach that supposedly balances the two sides’ concerns — one that gives up on the possibility of resolving the conflict and focuses instead on “minimizing it.”

To exemplify this approach, Goodman sketches out two alternative political arrangements that could be pursued. Neither entails the creation of an independent, sovereign Palestinian state alongside Israel, and neither requires Israel’s withdrawal from the West Bank. And for Goodman, this is the point: “Neither hope to solve the conflict,” he writes, “only to convert it from a fatal situation into a chronic one.”

Goodman associates his first proposal with the politics of “the moderate left.” He calls it “the partial-peace plan,” under which Israel would relinquish “the populated areas” of the West Bank (presumably Area A, which contains most Palestinian cities, although he does not specify) while retaining control “over the areas it needs for its own defense,” which he does specify — the Jordan Valley and the existing settlement blocs. While significant portions of the West Bank would remain under Israeli control, Goodman asserts that it would in theory leave open the possibility for a territorially contiguous Palestinian state on whatever remains.

For Israel, the advantages of this plan are clear: it can claim that it has ended direct rule over Palestinians while keeping large swathes of the West Bank. For the Palestinians, who, Goodman concedes, would be unlikely to accept this plan, it would give some kind of state without having to forgo certain demands, such as the right of return, within that territory.

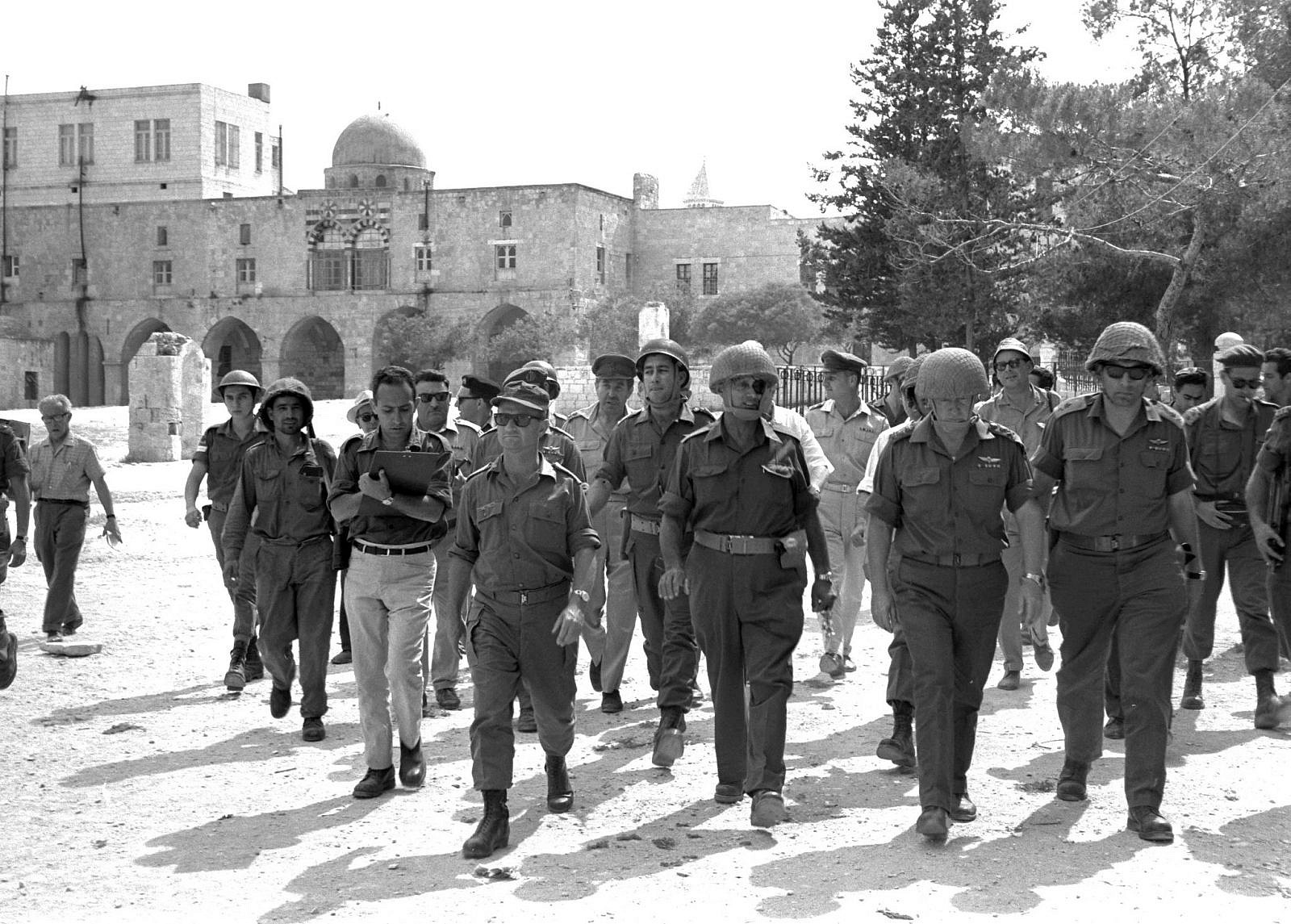

Goodman presents the “partial-peace plan” as the product of maverick thinking — a radical shift from ending the conflict to reorganizing it. But this kind of plan is nothing new to Israel’s defense establishment. In July 1967, shortly after the Six Day War, then-Defense Minister Yigal Allon proposed that Israel maintain military control over the Jordan Valley and make the Jordan River Israel’s eastern border, while withdrawing from areas with high Palestinian populations.

The logic of the Allon Plan became the basis for much of Israeli policy in the West Bank in the following decades, and continues to inform many contemporary Israeli leaders. Goodman acknowledges this fact — and that no Palestinian leader has ever accepted such a plan — but insists that this time it will be different because, unlike previous negotiations, “this would not be a deal to forge a peace but to terminate a state of war.”

In statements like these, Goodman shows both his political cards and a kind of myopia. Unlike Hamas, the Palestinian Authority (PA) — which, after the Israeli government, is the main governing authority in the West Bank — is not at war with Israel. In fact, the PA carries out a significant portion of Israel’s dirty work: it is funded in part by Israel and actively cooperates with its security and intelligence services, including by repressing Palestinian dissent. The PA continues to do so even when President Mahmoud Abbas, in periodic exasperation with Israeli intransigence, pledges to end security cooperation (and never does).

Goodman admits that the focus of his book is not internal Palestinian politics, but his frequent treatment of the Palestinians as an undifferentiated, hostile mass leads him to omit crucial nuances and, more generally, to mischaracterize the political reality in the West Bank.

Goodman’s second and “moderate right” proposal, the “divergence plan,” takes as its starting point a 2016 remark by former U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger. According to Kissinger, in a Middle East witnessing multiple failed states from Libya to Iraq, the prospects for an independent Palestinian state would not only be slim, but potentially catastrophic, with refugees and Islamist militants knocking on the door. The more realistic alternative, Kissinger says, is to maintain the PA as a pseudo-state while increasing its “zones of control, national symbols, and attributes of sovereignty.”

Goodman adds to Kissinger’s suggestion the possibility of granting Israeli residency to Palestinians living in Area C, who would fall outside of the PA’s “zones of control” — replicating Israel’s policy toward Palestinian residents of occupied East Jerusalem (which Israel unilaterally annexed in 1980, in violation of international law). These two “parallel, complementary processes,” Goodman writes, “would bolster the impression of Palestinian sovereignty in symbolic terms and minimize the control over the Palestinians in practical terms.”

Goodman is aware that granting residency to Palestinians living in Area C may sound like annexation, but he stresses that this, too, is different. “This is not a case of annexing the territory, but granting rights to the people who inhabit it,” he insists, adding in a footnote that the similarity to Naftali Bennett’s plan to annex Area C is superficial. Bennett’s proposal, Goodman writes, “does not serve to extricate Israel from its Catch-67.”

By this, Goodman presumes two different things. The first is that Bennett’s call for annexation carries an implication of finality, which Goodman’s proposals aim to avoid by minimizing the conflict’s costs in both resources and human life instead. The second is that Bennett’s proposal could upset the careful demographic balance that preserves Israel’s Jewish majority, thus contravening the old Zionist dictum: maximum land, minimum Arabs.

Goodman acknowledges that his proposals would likely run up against international opposition, but he argues that this should not be an obstacle: “Since these initiatives would seriously reduce the friction between Israelis and Palestinian civilians, they would also seriously reduce the friction between Israel and the international community,” he writes.

The philosophy undergirding Goodman’s proposals is, as he puts it, “a modest conception of politics” that is “about not solving problems but restructuring them.” According to this line of reasoning, the conflict between Israel and the Palestinians is not one that can be solved given the two sides’ irreconcilable claims, but one whose negative aspects can be controlled, reduced, and transformed.

Viewed from another angle, both plans essentially seek to make the occupation more sustainable and less expensive, more tenable and less noticeable — to guarantee its persistence into perpetuity. In fact, when he refers to the occupation, Goodman seems to believe that it only slightly exists. One of the many inventive yet fallacious assertions he makes throughout the book is that “the territories are not occupied, but the Palestinian people are.”

To explicate this form of occupation-denial, Goodman argues that because Israel gained the West Bank in a war of self-defense against Jordan, the Jordanians, not the Palestinians, are the relevant injured party. Since the Palestinians could have theoretically demanded a Palestinian state while living under Jordanian rule, it is not principally Israel that has prevented Palestinian independence.

In this sense, Goodman claims, the Israeli right is correct that there is no occupation of the land; but the left is also correct that Palestinians in the West Bank live under foreign military rule, which is an unjust arrangement. For Goodman, this is another way his proposals are pragmatic: they thread the needle between the right and the left’s conflicting but equally valid claims.

Goodman’s twisted definition of the occupation, which makes a concession to the left while affirming the basic political assumptions of the right, is characteristic of the book as a whole. Catch-67, and the proposals it contains, takes a hardline right-wing position — that there will be no Palestinian state, that the occupation only sort of exists but also cannot end — and presents it as the most realistic and responsible approach to an intractable conflict.

Goodman recognizes that there is no shortage of reasons why the status quo is undesirable, including violations of Palestinian rights, but then puts forward proposals that only keep the status quo’s balance of power — Israeli-Jewish supremacy and Palestinian subordination — intact.

Put simply, Goodman’s “pragmatism” is a Zionist pragmatism, prioritizing Israeli Jewish concerns first and foremost: the primary goal, he writes, is to ensure “existential security” for the Jewish state. For all of Goodman’s insistence that he has offered something original, his ideas offer little change to the fundamental reality of endless occupation.

With Israel on the cusp of its third round of elections in one year, it is safe to say that Goodman’s book has not resolved Israeli society’s political divisions nor “healed the conflict” with the Palestinians — as no book can. Yet the spirit of Goodman’s ideas has ascended to the top of the Israeli political agenda.

For example, during the previous round of failed coalition negotiations between the Blue and White party and the Likud, Benny Gantz reportedly agreed to accept a Likud proposal for the annexation of the Jordan Valley. Now, in Blue and White’s most recent campaign to unseat Netanyahu, the Jordan Valley has become one of the few clear proposals offered by a party with an otherwise amorphous ideology and platform.

That the success of Goodman’s book has dovetailed with the rise of the kind of centrism represented by the Blue and White is hardly coincidental. Both claim to represent, in different ways, Israel’s silent centrist majority — the ordinary Israelis who reject the settler right’s fundamentalist messianism as well as the left’s commitment to Palestinian human rights.

“A vibrant and lively political center is emerging in Israel,” Goodman wrote in The Atlantic in April 2019. “The center is winning increasing support, but its platform is neither clear nor coherent. It possesses an ideology, but those beliefs remain largely unarticulated.” We can expect to hear more from Goodman as he articulates that ideology, while another year of occupation passes by.