Though often forgotten in Israel today, some of North Africa’s biggest cultural assets were in fact Jewish. Meet the stars who shaped Maghrebi music, from the classical to the contemporary.

By Ophir Toubul

‘There arose the idea of taking people who have nothing in common. The one lot comes from the highest culture there is — Western European culture — and the other lot comes from the caves.’

— famed Israeli poet, Natan Zach.

I, too, used to think this way, and I imagine that a large part of those who went through the Israeli educational system do too. And then I learned about Maurice el Medioni music. It has been seven years since the miracle – since I began re-learning my own history.

Through Maurice el Medioni I learned about dozens of Jewish musicians who were famous in North Africa, before the establishment of the State of Israel. Musicians who received and continue to receive prizes, who are the subjects of documentaries and are generally considered cultural assets of North African culture. It is redundant to state that most of this recognition takes place outside Israel. In Israel, these musicians were at best ignored – at worst they were ridiculed. The following list will provide an example of some of these artists, many of whom have been active in recent years.

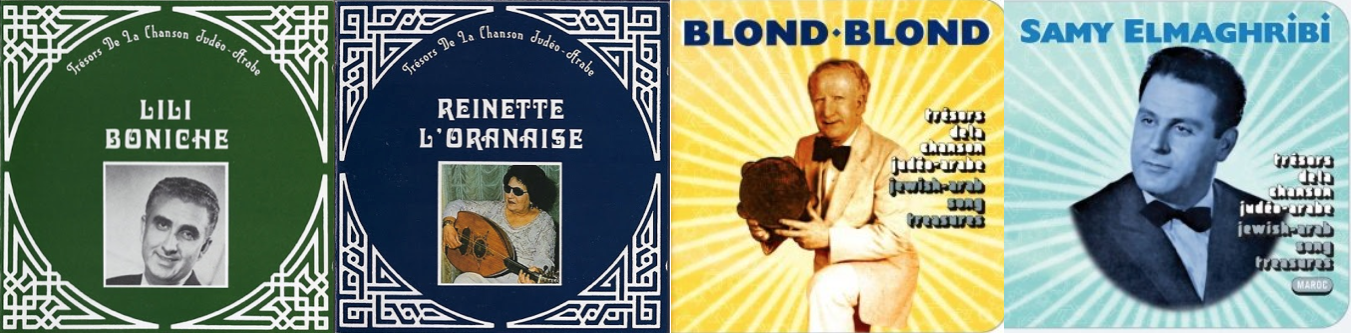

‘Treasures from Jewish-Arab songs’ – compilations from North Africa’s biggest artists. It was released in France in the 00’s:

A few months ago, I was honored to be part of a group of 20 people, the first Israelis to watch Les Port Des Amours, a documentary film about singer Reinette l’Oranaise. The film, which took no less than 23 years to reach Israel and was screened by the Institut Francais, follows the legendary blind singer/oud player who was loved by Jews and Muslims alike in her home country of Algeria, specifically due to her deep, inimitable voice and her knowledge of the country’s folk music.

The following clip is the only one I could find from the film on YouTube. We see Reinette arguing with her pianist, Mustafa Sakandari, on the length of the Istikbar – the introduction to the piece. In the subtitles, the word Istikbar is translated as “she refused,” because really, what are the chances that an Israeli translator will recognize and identify a common introduction that appears in every North African folk song.

The 2012 film Al Gusto attempted to create a “Buena Vista” for Algerian musicians. Director Safinez Bousbia walked through the Casbah in Algiers and the streets of Oran looking for the big musicians of the 1950s, when the Sha’abi genre was at its peak popularity in the cafes and hair salons in Algeria’s major cities. She collected them, one by one, including the Jewish ones who were uprooted from Algeria, in an attempt to establish the Al Gusto orchestra. The film follows the new-old orchestra’s tour, which continues across the globe today. Jewish artists such as René Perez, Luke Sharqi and Maurice el Medioni appear in the film, among others.

This film was also screened only a few times in Israel, but never made any big waves. One can find the orchestra’s full concert on YouTube, and clearly see the respect given to the Jewish singers.

‘Most of the Moroccans have not understood the idea of what we call the Western world. Perhaps their development is soon to come, perhaps it is happening now, but whatever they brought from Morocco is nothing to write home about. What did they bring? Mufletot? A culture of tombstones?’ Haim Hefer

A singer like Salim Halali, who was one of the great Jewish singers of North Africa, has a message that goes beyond his beautiful music, a deep message that resonates even today – on the future and the different possibilities that lay before us. Through his complex identity, Halali showed that it was possible for Jews and Arabs to live together, as well as someone who respects and follows religious traditions on the one hand, and a secular Westerner on the other hand. His style blurred the lines between masculinity and femininity, and his music showed how Arab and North African music, tango, flamenco and Jewish Ashkenazi music could live side by side in peace. The film Free Men (2011) tells Halali’s life story, and specifically the story of his rescue from the Nazis after being hidden by an imam in a mosque.

Over the past year in Morocco, a concert was held in honor of Haim Botbol, a singer who I had never heard of until that point. The large concert, which was held as part of a music festival in the city of Essaouira, was also filmed for Moroccan television. Alongside the concert, a catalogue featuring Botbol’s entire catalogue, covers of his records, as well as his life story were released. Had a number of bloggers and record collectors (such as Bashir “Tukdim” and Chris Silver) not brought the tribute concert to my attention, it would have passed me by completely.

And what was the fate of the North African artists who came to Israel? They had two choices: either squeeze themselves into the category of religious music and piyutim, or either stay in the Moroccan cultural ghetto or become a joke outside of it. This is how Sami Elmaghribi, who outside of Israel sang songs such as “Caftanek Mahloul” and established a jazz orchestra, focused on liturgical music in Israel. It is hard to imagine what kind of star Raymond Abakasis would have become had she not come to Israel. Or take Zahra al-Fasia, who was the first woman to be recorded on vinyl in Morocco, about whom poet Erez Biton wrote his famous poem. Jo Amar’s story is unique and complex, and Ron Cahlili dedicated an entire post to his story [Hebrew]. Cheikh Mouizo, Nino Bitton and dozens of others who made music here, who came to Israel with a rich musical past, did not even make it into this text, and were entirely forgotten. In a radio show recorded by Amit Hai Cohen and Reuven Abergil, one of them describes a singer by the name of Braham Swiri, who put out records in his youth yet lived the rest of his life in anonymity and sold his recordings outside the entrance to Jerusalem’s Mahane Yehuda Market.

‘Every ethnic group brought its own import. The Moroccans brought Mimouna, the Americans brought equality.’ Anat Hoffman, Chairwoman of Women of the Wall.

Dozens of years after the migration from Morocco to Israel, Moroccan culture is starting to undergo a revival. More young people are realizing that we did not come here from caves, and that we brought more than just Mufletot (a thin, crepe-like pancake traditionally eaten by North African Jews during the Mimouna holiday, after Passover). The search for our culture demands effort, but it is easier today due to YouTube and Facebook.

Kobi Peretz’s last album signals an interesting attempt to bring back the Maghrebi sound to Mizrahi music. It started with his hit “C’est La Vie” by Khaled Algerai, and continued with his inclusion of a Sami Elmaghribi classic “Omri Ma Nansak Ya Mama” as a duet with with his father, the singer Peti Armo.

And finally, the gem of the young Maghrebi artists in Israel: Neta Elkayam. A rare singer who pores over the treasures of North African music, and who started a fantastic band that revives that very same music. Just last week we saw her collaborate with Maurice el Medioni in Tel Aviv’s Barby Club, showing us that a different future is possible.

Based on a workshop that took place as part of the 2014 Piyut Festival. Thank you to Khen Elmaleh, Amit Hai Cohen, Amos Noy and Neta Elkayam for the comments. Read this article in Hebrew on Café Gibraltar.

Related:

Searching for song and identity, from the Maghreb to the Negev

Finding a place in the Middle East through music