Shimon Peres, the last member of Israel’s founding generation, was feted internationally as a visionary man of peace. His legacy is in fact far more complex, and often nefarious

The passing of Shimon Peres, at the venerable age of 93, precipitated an outpouring of elaborate obituaries and eulogies around the world, with news outlets noting that his political life spanned the entire history of the state of Israel from its founding in 1948. Peres was, in fact, the last member of the founding generation — the men and women who settled for ideological reasons in British mandatory Palestine and dedicated their lives to building the state of Israel. But while in his later life he came to be known on the international stage as a visionary statesman and a pursuer of peace, his legacy is in fact much more complex, and often quite dark.

As an early protege of David Ben Gurion’s, Peres was appointed at the very young age of 29 to director-general of Israel’s Defense Ministry. In that position Peres built and grew Israel’s arms trade with France. He also helped to establish the reactor in Dimona. Due to Israeli censorship, journalists are not allowed to acknowledge that the nuclear reactor exists. But “foreign sources” (and Colin Powell) say that the Dimona reactor marked the introduction of nuclear weapons to the Middle East.

With Peres at the defense ministry, Israel took a lead role in the 1956 Sinai Campaign. He exploited his French connections to position Israel as a client state of the European powers, and to embark on a war whose primary goals were to: establish Israeli control over the Sinai Peninsula; seize the Suez Canal from Egyptian sovereign control and hand the reins back to the French and British; and weaken anti-colonial forces in the region. The United States and Russia, then the world’s two new superpowers, ultimately forced Israel into a full withdrawal from the Sinai, but the message Israel sent to its neighbors was clear: we’re with the other guys — the Europeans.

Peres later served as a junior minister in the governments that followed the 1967 war, and which kicked off the settlement enterprise — an ongoing project of land theft and oppression, which the government knew violated international law from day one. But in those early days, Israel’s settlements in the West Bank, Gaza and Sinai were presented as the continuation of the same settlement movement that established dozens of kibbutzim across Israel in the 1930s, 40s and 50s.

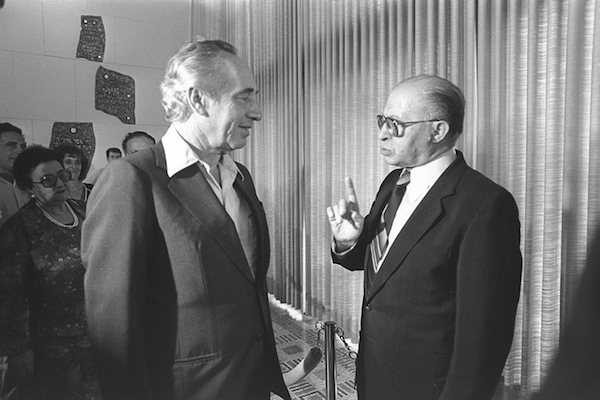

In 1975, it was Peres who lent government support to the first iteration of the “Hilltop Youth,” and actively supported the establishment of Kedumim and the Gush Emunim movement, which Rabin described as the settlers’ Trojan horse. As defense minister, Peres kept up the settlement movement’s momentum and opposed the return of territory (the West Bank) as part of a peace deal with Jordan. Today, the Hilltop Youth are the most violent, radicalized settlers in the West Bank.

These were also the years that Peres, who would go on to win the Nobel Peace Prize, promoted arms sales to various countries across the world. An investigative report by The Guardian found documentation that Peres helped sell nuclear warheads to South Africa when it was governed by the apartheid regime. The Office of the President denied the claims.

Dozens of years later, as president, arms dealers remained among Peres’ friends, and often funded his extravagant celebrations.

Shortly after he was elected to head the national unity government in 1985, Peres — along with Likud’s Yitzhak Moda’i — advanced the largest plan to privatize state assets ever seen in Israeli history at that point. Along with steps to reduce the national debt and state expenditures, they essentially did away with the very idea of a welfare state. They laid the groundwork for the neoliberal economic s that has guided Israeli policy ever since. And while Peres’s economic plan was a response to the massive crisis created by the Likud government, but he plucked his remedies from capitalist schools of economics instead of socialist economic thought, the latter of which Labor professed to subscribe.

In 1984, during his first, short term as prime minister, Peres tried to whitewash the murder of Palestinian hijackers in the Bus 300 Affair. The Affair, which involved revelations that the hijackers were beaten to death during interrogation after they were photographed alive and in custody at the scene of the hijacking, was at the time a major scandal in Israel. Peres later helped to secure pardons for the interrogators who had murdered the Palestinian prisoners.

But he refused to pardon nuclear whistleblower Mordechai Vanunu, who revealed to the world only a bit of what was taking place in Dimona. In fact, it was Peres who ordered the Mossad to abduct Vanunu from Europe and bring him to Israel, where he was sentenced to 18 years in prison following a closed trial.

It was only in 1992, when Yitzhak Rabin was prime minister, that some bright spots start to appear in Peres’ political career. As Ron Gerlitz and Nidal Othman wrote here, relations between the state and its Arab citizens reached an all-time high when his government, for the first and last time in Israeli history, relied on a partnership with Arab members of Knesset to form a ruling coalition. Peres also helped build public support for a peace based on two states, a proposal that still enjoys the support of a majority of Israelis and Palestinians.

And yet, the deal for which he was ultimately responsible, the Oslo Accords, was a disaster. Without actually ending the occupation, Peres managed to free Israel from its responsibility for Palestinians’ welfare and day-to-day lives by creating the Palestinian Authority. Thus, while Israel still maintains control over almost every aspect of life in the occupied territories, the Palestinian Authority is saddled with all of the responsibility, without any authority to act independently of Israel.

The Oslo Accords preserved Israeli supremacy in the territory west of the Jordan River, with military force and control over natural resources like water, but also led to the creation of burgeoning class of people with vested interests — from PA bureaucrats to private entrepreneurs — whose livelihoods are entirely dependent on Israel’s good graces. And that’s just the tip of the iceberg (read more here).

Yet despite all of that, after the Rabin assassination, Peres could have chosen to leverage the nation’s anger and shock in order to seriously advance the peace process. Instead, a month before national elections he decided to embark on a devastating military campaign in Lebanon, “Operation Grapes of Wrath,” which killed 113 Lebanese civilians (along with three Israeli soldiers, and 21 combatants from Hezbollah and the Syrian army). Most of the dead were killed in the “Qana massacre,” when Israel shelled a UN compound where hundreds of civilians had taken cover. (And yes, responsibility for the Qana massacre rests on Peres’s shoulders, too.) Peres never got the security cred he was looking for from that military operation. At the same time, he missed an opportunity to cast himself as the only leader committed to pushing for peace and finishing the process Rabin started.

After losing the premiership to Benjamin Netanyahu in 1996, Peres eventually returned to government in 1999-2002, the start of the Second Intifada and subsequent violent suppression dubbed Operation Defensive Shield. At the end of that year he again left the government. But a few years later Peres was back in the coalition, in order to support Ariel Sharon’s disengagement from Gaza. The disengagement was a unilateral withdrawal that rewarded Hamas instead of resting on a negotiated agreement with the PLO. This was a mistake to which he later admitted.

In the largely ceremonial office of president (2007-14), Peres demonstrated his detachment from the social needs of ordinary Israelis. The operating budget for the President’s Residence doubled during his term in office (it has since been reduced under President Rivlin). The luxurious “President’s Conference” he organized every year was funded by industrialists, Wall Street types and arms dealers, some of whom have ties to tyrannical and murderous regimes. It is no coincidence that Peres was awarded the “Spirit of Davos” award from the World Economic Forum, a group dedicated to advancing neoliberal economics globally.

After his term as president, Shimon Peres became a lobbyist for Israel’s largest bank, Bank Hapoalim, and for international pharmaceutical giant Teva. He also remained involved with the Peres Center for Peace, which he humbly founded in his own name.

The Peres Center aptly sums up the legacy of the Nobel laureate, former prime minister and president. The Center, which itself has become a forum of extravagance for the wealthy, was built in one of the poorest areas of Jaffa’s Ajami neighborhood. It overlooks the sea, but has its back to Jaffa and its Palestinian residents. Behind the decadent palace of peace, just across the poorly paved road, are impoverished and crumbling tenement blocs. In three directions the Center resembles a fortified monstrosity; only on one side, the one facing the sea, a telling westward gaze, is its glass facade magical and inviting. It is, perhaps, the perfect metaphor for Shimon Peres’s legacy.

Thanks to my brother, Oren Matar, for help researching this article. A version article was first posted in Hebrew on Local Call. Read it here. The English version has been revised since it was first published.