For young Palestinians, Nakba Day is dedicated to remembering the catastrophes that our grandparents went through. But with every passing year, we realize how much the day belongs to our catastrophes too.

My maternal grandfather was born in 1929. Although Alzheimer’s disease eroded his memory during the later years of his life, he had a surprising knack for recalling his experiences growing up in Haifa under the British mandate of Palestine. He described the open plains he crossed with friends to swim at the beach; the diplomats and missionaries who traveled through Haifa’s German Colony; and the port and railway that linked Palestine to other Arab cities and the Mediterranean region. Although he couldn’t remember that he had repeated these stories countless times before, I never grew tired of hearing them; they breathed life into a world I could only read about in books and gaze at through black-and-white photographs.

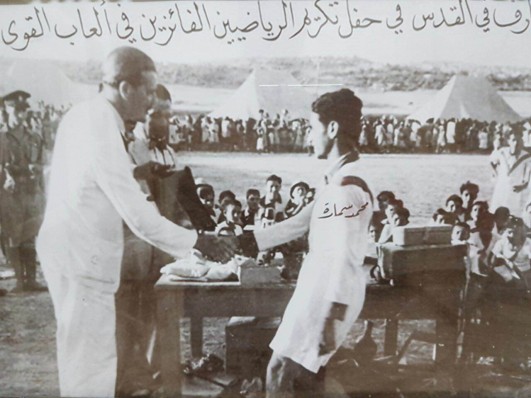

Like all Palestinians of his generation, my grandfather lost that world in 1948. At the time he was living in Tira and studying at a British school in Tulkarem, but when the war broke out he joined a local resistance group to fend off Zionist forces from the village. The armistice agreement made Tulkarem part of the Jordanian-ruled West Bank, while my grandfather was made an Israeli citizen in Tira. For 18 years he lived under Israeli military rule, watching the village’s lands being confiscated and used to build new Jewish settlements. When he wanted to leave the village, he had to get a permit. When he wanted to walk to a neighboring field, he had to be searched at a checkpoint.

Military rule ended in 1966, and my grandfather – by then a historian and a teacher – was able to explore the land again. But the country he remembered had changed. Hundreds of villages and their inhabitants had disappeared. The main road going up Haifa’s Carmel mountain was no longer known by the Arabic “Shere’ al-Jabal” but by its new Hebrew name “Derech Hatziyonut.” When Israel captured the West Bank and Gaza the following year, the soldiers who once guarded the entrance of Tira were now stationed near his old school in Tulkarem. The occupation was both a gift and a curse: it allowed my grandfather to reconnect with his Palestinian brethren, but at the cost of their subjugation under the same regime he had endured.

For young Palestinians, Nakba Day is dedicated to remembering the catastrophes that our grandparents went through. But with every passing year, we realize how much the day belongs to our catastrophes too. The war in Syria is displacing another generation of Palestinian refugees from camps like Yarmouk. The blockade and attacks on Gaza are crippling its society and separating them from their compatriots in the West Bank. Home demolitions in the Naqab (Negev) are dispossessing hundreds of Bedouins from their lands every year despite their supposed protection of Israeli citizenship. The list goes on.

My grandfather passed away two weeks after Nakba Day in 2014. For me, his death wasn’t just the loss of a family member and a personal inspiration. He was living proof of a time before 1948 when the land, though embroiled in changes that weren’t fully understood at the time, enjoyed a small semblance of peace that the following generations haven’t known. Perhaps that was why he became a historian and a teacher, hoping that by instilling his memories into the minds of the youth, he could keep his lost world alive.

That world is long gone. But it seems my grandfather, together with other Palestinian elders, were right to place their faith in the stories they left behind. Today, young Palestinians are retelling their grandparents’ experiences using mediums from film to social media. Every year thousands take part in a “March of Return” to villages uprooted in 1948, as they did last week in Wadi Zubaleh and Tirat al-Carmel in Israel. And millions around the world are joining the Palestinians in solidarity as they struggle for their freedom and dignity.

Nakba Day is therefore not just about mourning the pain of 1948. It is about celebrating the power passed on to us by our grandparents, whose stories helped to revive a society when their homeland was almost nothing but a memory. Many Jews in Israel and the diaspora, whose own identity is heavily influenced by the experience of loss and trauma, have yet to recognize those stories; just as many Palestinians have yet to sympathize with the memories of racism, dispossession, and genocide from the grandparents of Jews. Nakba Day should be the time to start ending that denial.