Kochavi Shemesh, one of the legendary leaders of the Israeli Black Panthers, believed that the liberation of Mizrahim was bound up with the freedom of Palestinians, black South Africans, and other oppressed people. He passed away last week at the age of 75.

By Asaf Shalev

Kochavi Shemesh, who was born in Iraq during World War II and grew up in the dilapidated and war-ravished slums of Jewish Jerusalem in the 1950s, never received formal schooling. He didn’t even finish first grade.

The lack of education didn’t stop him from founding and editing a community newspaper as an adult in the late 1960s. What did stop him was a visit from the police soon after putting out the seventh weekly issue. The crime? Operating a newspaper without a permit, a legal requirement that was in place in Israel until 2017. Shemesh had thought of applying for one but he didn’t qualify because he’d never earned a high school diploma.

“The paper came out every Saturday evening,” Shemesh later recalled in a 1971 interview with Maariv. “It contained sports news and Sephardi human interest stories. It did well. We fostered Sephardi consciousness.”

A judge gave Shemesh a choice of paying a small fine or serving a three-week prison sentence. On principle, he chose prison.

Autodidactic and strong-minded, Shemesh, who died last week at age 75, hitched his talents to the cause of social justice. Chiefly, he championed the rights of Mizrahi Jews, but his solidarity extended far beyond that — to Palestinians, Vietnamese, black South Africans, and others.

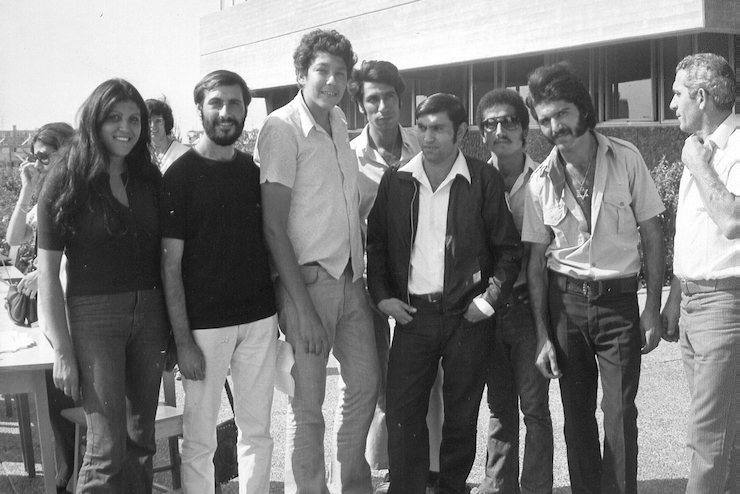

In early 1971, a group of Israeli youth stunned and scandalized society when they rose up as the Black Panthers of Israel, summoning the specter of civil turmoil from across the globe. A friend introduced Shemesh to the firebrands and he immediately joined the group.

His affiliation with the Panthers solidified on May 18, 1971, a date that would forever be known in Jerusalemite lore as the Night of the Panthers. The events started unfolding peaceably enough with a rally of several hundred Panthers at the city’s Davidka Square.

The Panthers moved through the crowd passing out leaflets with their demands and ideology written out in bullet points. Loudspeakers amplified speeches. One protester held up a sign that declared:

“Join the Black Panther Rebellion

The Rebellion of the Sephardim”

As the rhetoric escalated, the crowd began to swell into the thousands. They had warned the authorities from the beginning: continue to sideline us and we will eventually explode in your faces. Someone shouted, “To Zion Square!”

The crowd didn’t need much prodding. A mass of people started to march down Jaffa Street, Jerusalem’s main thoroughfare, their bodies blocking traffic, their voices filling the air with the discordant sound of protest chants: “Ku-la-nu Pan-te-rim!” We are all Panthers.

On the march to Zion Square, a distance of just over a third of a mile, the Panthers passed through the city’s shopping and dining district. Vendors folding up their wares at the end of the day paused to behold the spectacle. Shoppers poured out of the narrow storefronts clutched their bags and watched the parade of protestors. Some, magnetized and galvanized, joined in. There was no sign of police.

The square emerged in view and still, it seemed, the guards were absent and the palace was up for grabs. A young man with a thick mane of black hair split from the crowd. He sprinted ahead shouted over the general din: “We are going to change the name of Zion Square to the Square of Mizrahi Jewry.”

As the demonstrators filled the center of the square, a clot of police dressed in full riot gear suddenly appeared out of a nearby alleyway. An officer raised a bullhorn to his face. “This demonstration has been declared an unlawful assembly,” he said, “I give you two minutes to disperse!”

“Boo!” the Panthers yelled back. At the top of their lungs, the leading Panthers ordered everyone “Don’t budge!” And the crowd obeyed. People stayed put even as the menace of cudgels, shields, and steel helmets drew in closer and closer. For a moment nothing happened; the chasm of asphalt between opposing battle lines remained empty.

But the commander sicced his police on the protestors and a rain of billy clubs came down. The cops captured territory swiftly. They paused only to snatch those unfortunate few who failed to retreat in time. Mounted officers appeared in the square followed by an armored tactical vehicle adorned with water cannons. Within minutes the square was mostly cleared and traffic restored.

The demonstrators were pushed to the margins of the square and some disappeared into the alleys but they did not disperse. In fact, their numbers only seemed to grow. Thousands of ordinary Israelis joined in against the cops. The Panthers themselves split into small groups, darting out to hurl taunts, abuses, and glass bottles at the cops and then withdrawing. The fury of the riot control squads was fully unleashed at this stage and they made no apparent effort to distinguish between protestors and onlookers.

The water cannons were even less discerning as they squirted high-pressure jets of liquid, dyed green, in every which direction. The flailing torrents even hit some police and eventually also a baby carriage, whose tiny occupant had to be evacuated to the hospital. The aggressive conduct by police inflamed the crowds, who yelled at them, “you’re Nazis!”

It was one of the most significant civil disturbances of its kind in the country’s history. Seventy-four people were arrested and dozens were hospitalized with serious injuries.

Shemesh was among them. His hospital registration card noted that he suffered from polio, causing him to limp, and reported that Shemesh “had sustained blows to his legs” in the course of the night (thanks to cops who had sussed out his vulnerability).

Elected chairman of the Panthers for a period, Shemesh tried always to move the group left. When the World Zionist Congress assembled in Jerusalem in 1972, he led a demonstration against it arguing that it “does not speak for the all the Jews in the world.”

The following year, in the summer of 1973, Shemesh joined a delegation of communists and flew to East Berlin for the 10th World Festival of Youth and Students. Two of the figures headlining the event were Yasser Arafat and Angela Davis. Shemesh met Davis briefly. He learned from her to never again refer to degrading work as “black labor.”

Shemesh ran for Knesset in the election that immediately followed the 1973 war. He lost. Soon after that, a correspondent for the New York Times featured him in a series of portraits of Israelis, famous and ordinary. “Our strongest bond is with the poor and oppressed in the Middle East,” Shemesh was quoted as saying. “The Zionist movement was formed to keep a European culture in Israel.”

“Our interests lie in seeking an alliance with the Arabs and forming an economic bloc to counter the influences of both U.S. and the U.S.S.R.,” he continued. “I fully support the Palestinians’ desire to found a separate state on Israeli soil. The treatment of the Palestinian Arabs is one of the highest crimes of the Zionist state.”

In the decades that followed, not many people found his ideological positions compelling or even tenable. Yet, as his oratory skill developed, none dismissed Shemesh as foolish or unserious.

After the fall of the Soviet Union, he advocated, again unpopularly, for stemming the mass arrival of Soviet Jewry until Israel’s own destitute were cared for. Shemesh himself provided for the needy — for example, as a co-founder of Zoharim village in the early 1990s, Israel’s first drug addiction recovery center.

That experience convinced him that Israel’s criminal justice system was inherently unfair, punishing precisely the people who needed help the most. He teamed up with other Panthers and mounted a campaign to demand general amnesty for the country’s inmates—in other words, he became a prison abolitionist.

In 2003, the elementary school dropout earned his law degree and became full-fledged attorney, soon joining the board of the Association for Civil Rights in Israel.

Shemesh is survived by his wife Rachel Ashur Shemesh, three children, numerous grandchildren, and a entire generation of Mizrahi activists.

Asaf Shalev is a journalist based in California. He is completing a book about the Israeli Black Panthers with UC Press. Find him on Twitter: @asafshaloo.