‘To bring in gas we need a permit. To bring in sacks of flour in we need a permit. And when we get a permit, we arrive at the checkpoint and they tell us we have no permit.’

By Moriel Rothman

There are only 10 homes left in the small Palestinian village of Nabi Samuel, just northwest of Jerusalem. The remaining families are fighting an uphill battle to continue living in their homes.

As its name indicates, Nabi Samuel is home to the proclaimed burial site of the Prophet Samuel. In the 11th century, Christian crusaders built a fortress and church on top of the tomb. When Salah a-Din conquered Palestine in the late 12th century, the church was turned into a mosque and the village of Nabi Samuel was built around it; layers upon layers. Then came the bulldozers.

Eid Barakat was seven years old in 1971 – four years after Israel occupied the West Bank and the small village of Nabi Samuel. “They came at dawn and loaded us onto trucks. We were young, so we treated it as a game. We didn’t understand why our parents were weeping.”

Israeli bulldozers destroyed most of the village that day, leaving only 10 homes standing on the edge of village. Today, the area around the tomb and mosque is a popular Israeli tourist site, replete with signs that go into detail about the ancient past but make no mention of the contemporary destruction. The 10 houses on the outskirts of the village make up what remains of Nabi Samuel. And those remains are being threatened as well.

Between ‘Greater Jerusalem’ and a segregated highway

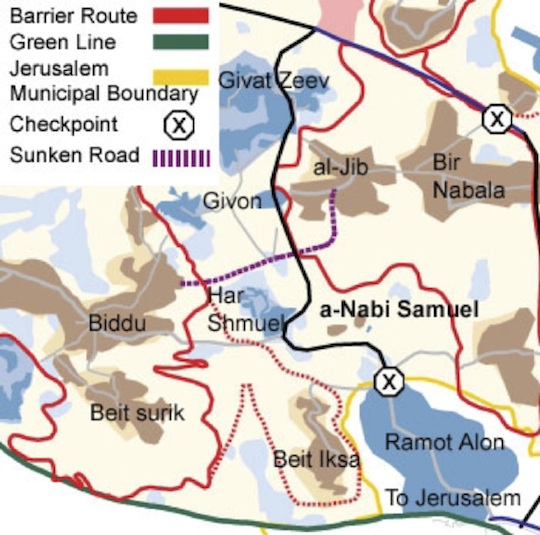

Since Israel’s completed its construction of the separation barrier in the Nabi Samuel area some four years ago, the village has been trapped inside what residents and activists call an “invisible cage.” To the east and west, the village is fenced in by the separation barrier; the nearest checkpoint to Ramallah is located five kilometers away. To the north it is blocked off by Highway 443, which Israelis may know as a convenient bypass road running from Jerusalem to Ben-Gurion Airport, but which Palestinians have come to know as a direct source of dispossession and of subsequent segregation for much of the past decade.

And while south of the village there is seemingly unrestricted passage to the East Jerusalem settlement of Ramot and the rest of holy city, in reality it is unrestricted for Israelis only. If a Palestinian resident of Nabi Samuel is caught in Jerusalem without a permit, he or she is likely to face fines or jail time. In this corridor between Ramot and Highway 443 lie the settlements of Heruti, Har Shmuel, Givon HaHadashah and Givat Ze’ev. The only things preventing the corridor from becoming a Jewish-only zone are the small village of Al-Khalayleh, which has been subjected to harassment and arbitrary demolition by the Israeli army and civil administration, and little Nabi Samuel. It would be very convenient for Israel if Nabi Samuel simply disappeared.

Toward that goal, the Israeli military has put great pressure on Nabi Samuel and its residents, making their lives almost unlivable.

Forbidden flour and smuggled chickens

“We can’t bring anything in here,” says Eid Barakat, a 50-year-old farmer who has recently become involved in activism aimed at protecting his native village.

“To bring in gas we need a permit. To bring in sacks of flour in we need a permit. And when we get a permit, we arrive at the checkpoint, and they tell us we have no permit,” he explains.

But residents of Nabi Samuel have – literally – found ways around these draconian restrictions. Nawal Barakat, Eid’s wife, is the president of the Feminist Association of Nabi Samuel, which focuses on building and strengthening the community through planting gardens, organizing photography workshops, and, in February of this year, smuggling in chickens.

Smiling, Nawal tells how the association received a donation of egg-laying hens from the Norwegian Consulate. Like flour and gas, it was clear that the hens would not be allowed through the checkpoint.

“They claim we will sell the eggs to the Jews in Jerusalem,” Nawal says, laughing, “but we don’t want to sell the eggs to the Jews in Jerusalem. We want the eggs for our community.”

So what did you do? I ask.

“We carried the chickens through the hills,” Nawal replies, pulling up a picture of the fowl-smuggling expedition on Facebook .

I asked if I could use the picture for this piece, and she replied, without a moment’s hesitation, “of course. I am not afraid. I would do it again.”

National parks and national discrimination

The Rabin government declared the 3,500 dunams (865 acres) around Nabi Samuel to be a “national park” in September of 1995, just before the Oslo accords came into effect, after which it would no longer have been possible do so. In addition to functioning as a method of unilateral takeover, the national park designation allows Israeli authorities to enforce a strict, “no-changes-allowed” park building policy.

Eid goes inside and comes back with a stack of papers. “These are demolition orders,” he explains, and as he lays them on a small table, each order’s absurdity outdone by the next. An extension to a house? Demolished. A small fence to keep animals in? Torn down. Nineteen olive tree saplings planted? Uprooted.

Between disappearance and steadfastness

IDF Civil Administration chief planner Daniel Halimi was recorded last year saying about Nabi Samuel: “There is no village. There is a park.”

Around the same time, Eid, Nawal and other residents got word that the Civil Administration was planning to confiscate an additional 187 dunams (46 acres) of privately owned land in Nabi Samuel in order to further expand the park.

Fed up, Nawal, Eid and others erected a protest tent at the entrance to the tomb/Mosque/tourist park/remains of the village. “On the first day,” Eid says, “the Israeli army captain came to me and said, ‘you have five minutes to get out of here.’ I said to him, ‘Five minutes is a lot. If you’re going to force me to leave, do it now.’ The captain and others consulted amongst themselves for a longtime, and then left us alone.”

For the next few months, residents of Nabi Samuel, sometimes joined by Israeli, Palestinian and international activists, erected the protest tent every week, seeking to “call the world’s attention to the story of Nabi Samuel.”

When I asked Eid and Nawal if they’d seen any successes stemming from their protest they both nodded. Media has started to pay attention; foreign consuls and activist groups have stopped by. “There were even tourists,” says Nawal, “who stopped, listened to us, and were shocked by what they heard.”

Over the past few months, however, activity in the protest tent has slowed. According to Eid, only about 20 percent of the village ever took part in the public protests. “People are scared: they’re scared that the army won’t let them pass through the checkpoints, that they’ll be targeted and singled out. And they’re right.” Two days ago, Eid and Nawal’s son was barred from crossing the checkpoint, and when he argued, he was a soldier hit him and detained for 24 hours. Since the wall closed in on the village, almost a third of its residents have left, deciding to seek a life a bit farther away from the national park and its demolitions, siege and threats.

“We are staying here, though,” Eid says. “Maybe we will eat dry bread, but we will not leave.”

Moriel Rothman is an American-Israeli writer, poet and activist who works with Just Vision. This piece was originally written for Just Vision’s channel on the new Hebrew-language website, Local Call.

Related:

WATCH: Nabi Samuel – a village in a cage

WATCH: Al Walaja – The story of a shrinking Palestinian village