Saleh and Muhammad head out to their agricultural land. A settler stops them and calls the army. Four soldiers arrive. One of them empties his magazine into the two. Three other soldiers claim they didn’t see anything. The IDF says that the cousins attacked the soldier, then retracts the claim. No one is brought to justice. The fourth installment in a series examining the case files of soldiers who killed unarmed Palestinian civilians. [Read parts one, two and three.]

By John Brown* and Noam Rotem

Translated from Hebrew by Ofer Neiman

This series of reports deals with cases in which “uninvolved” Palestinian civilians were killed, as well as the superficial investigations into those killings conducted by the Israeli Military Police. No one has been brought to justice in any of these cases, but this case is unique nevertheless. Not because of the victims, whose names are remembered only by their families. Not even because of the soldier who took their lives, and, according his own testimony, even ripped down a poster mourning their deaths. The unique aspect is the way the IDF Spokesperson changed its story.

At first, the IDF Spokesperson published the claim that “a terrorist attack with a pitchfork had been foiled at a checkpoint,” and that two terrorists had tried to attack a soldier using pitchforks. The IDF was later forced concede that the report was inaccurate, and then claimed that the soldiers were attacked with a bottle and a syringe. With every new report, the volume knob was turned down a bit, until the last one, a day after the incident, according to which the two cousins were not terrorists at all, but two young men stopped by settlers after they had entered their own land — without coordinating with the army. But the IDF Spokesperson’s story had already gained prominence. Every Palestinian is a terrorist until proven otherwise.

The chain of events, leading to the moment in which an anxious soldier fired 29 bullets into the bodies of the two cousins, Saleh and Muhammad Qawarik, farmers who woke up early that morning to work their land, shows the null cost of Palestinian lives in the occupied territories. This involves the dubious initiative of a settler with a vast criminal record, one hyperactive shooter and three soldiers who do not remember anything, having managed to miss all 29 shots.

The IDF Spokesperson declined to comment for this article.

‘Their hands are soft to the touch’

On March 21, 2010, the two Qawarik cousins headed from their house in Awarta towards the family land. Later, it would be claimed that they actually intended to collect scrap metal by the side of the road, but in any case, there is no debate about the fact that they had no intention of hurting anyone when they left home that morning. They had taken two hoes and a bottle of water, and headed on foot along the road leading to the plot they owned.

At some stage, Avri Ran, an extremist settler who has been convicted of a series of violent offenses, and calls himself “The Sovereign,” passed by. Ran decided that the two had no right to be there, on their land. He stopped his car, and detained the two by ordering them to sit on the ground, and standing at a distance of 10-15 meters (30-50 feet) from them.

Ran alerted Nahshon Gideon, the security coordinator of the Gideonim outpost (near the settlement of Itamar), and the latter quickly arrived. Lior confiscated the hoes belonging to the two cousins, pointed his weapon at them, and the two settlers waited there for the IDF soldiers.

Ten minutes later, four soldiers of the IDF’s Kfir brigade, arrived at the scene and Ran left. The patrol commander, A., thought the two cousins were talking too much to one another, and therefore he sent Muhammad to sit under a tree on the other side of the road. According to the security coordinator’s testimony, A. questioned the two cousins in Arabic. According to A., the person who spoke to the two was the patrol’s Bedouin driver.

A. and the security coordinator soon decided that the two cousins were suspect. The reason? “Their hands were soft to the touch.” Not rough and hardened as the hands of Palestinian farmer should be, so they thought. After a while, the security coordinator left the scene as well, and the soldiers remained alone with the Palestinians whom they had not arrested, were not suspected of anything. Just people on their way to work.

How can anyone not hear or see the firing of 29 bullets?

A. contacted the brigade’s operations room on the radio, and extensive communication took place for two hours, on the radio as well as by text messages, between him and G., the deputy company commander. G. would later testify that there had been previous cases of abusing Palestinians in the battalion, and therefore he ordered A. not to handcuff the two — because “there was no reason.”

All that time, A., who appeared to be hyperactive, according to the investigator who questioned him later, was very close to Saleh. D., a soldier who was tasked with guarding Muhammad, was standing at a distance of 10-15 meters, leaning on the jeep. The two other soldiers did not leave the vehicle, and claim they did not see anything. One of them went as far as arguing he was “sleeping off to the side” (he would later retract this claim).

From this point on, everything the Military Police investigators know comes from A. the shooter. D. claims he did not see anything.

According to A., Saleh asked to pee. He took his water bottle and went a few steps away. When he returned, so claims A., he picked up a stone, 20 centimeters by 30 centimeters, and when he asked Saleh what he was doing, Saleh placed the stone back and sat down. A. says he then cocked his weapon quietly.

The two cousins asked to pray. After the prayer, they sat down separately again, and then. according to A., he saw Saleh put something in his pocket. When he asked him what it was, says A., Saleh rose up all of a sudden and swung the object in the air, as if to strike him. A., who claims he was under stress and fear, switched off the safety catch of his weapon, and fired approximately 10 bullets, seven of which hit Saleh in his upper body, from a very close distance. D., who was standing about 10 meters (30 feet) away, claims he did not see anything.

Only when A. finished firing at Saleh, did D. bother to turn his head in the direction of the shooting, yet he still missed the next development somehow: Muhammad, who was sitting around 15 meters from D. and 25 meters from A., stood up. A. emptied everything left in his weapon’s magazine, 19 bullets, into Muhammad’s body, until he, too, fell lifeless to the ground.

D. did not see this either. The two other soldiers who were sitting in the military vehicle also claim they did not witness the the entire period of time in which A. emptied an entire magazine, shooting the two members of the Qawarik family. In order to substantiate his claim, one of the two explains that the vehicle was facing the opposite direction to that of the shooting. A. claimed exactly the opposite. The investigator did not confront the two contradictory witnesses, or even examination this decisive point. The questions regarding which way the jeep was facing, and how can it be that a soldier empties an entire magazine into two people and no one around him sees anything — have not been resolved.

No fingerprints

The soldiers claimed in their interrogation that Muhammad had held in his hand a plastic syringe that was found at the scene. The needle must have been broken when it fell, so claimed A. in his questioning. A bottle and a syringe (without a needle) were indeed found at the scene, and the items were sent to the Israeli national police’s forensic lab in order to pull fingerprints from them. No fingerprints were found.

If one of the two cousins indeed swung these objects, surely at least one fingerprint should have been found on them, even a partial one. But no, nothing. Zero fingerprints, according to the forensic report. The Military Police investigators did not bother to mention this critical detail even once during the questioning of the soldiers.

Nothing was left of the shooting soldier’s version (the IDF Spokesperson’s pitchfork version had been refuted earlier): the shooter’s fellow soldiers do not corroborate his version (but also fail to provide any other information), and the evidence at the scene does not match his claims.

What really happened that day? Why did A. shoot the two Qawarik cousins? Did he intend to shoot them, or did he panic and lose control? The Military Police investigators were not particularly interested in those questions.

Another detail that has caught our attention is the fact that A. carried on with his duty the very next day. In his testimony he even recounts that he stopped in Awarta in order to remove a poster with the photos of the two cousins he had killed a day earlier. He would later take pride in showing the poster to the Military Police investigator.

The operational debriefing: A. is demoted

Following the shooting, A., the patrol commander, ordered the other soldiers to get out of the vehicle and put on their helmets, and then he reported what he had just done on the radio. Dozens of officers quickly arrived at the scene and initiated an operational debriefing.

The army regards such debriefings as a tool for analyzing operational incidents. Debriefings are held shortly after incidents, and according to army procedures, the contents are not to be passed to the investigating authority (namely the Military Police). Even if a person admits to murder in the operational debriefing, this admission cannot be used in his trial, and will not even be passed on to the investigators.

Why is this important? Because immediately after the debriefing, an officer in the Central Command spoke to a Haaretz journalist, saying that, “according to a preliminary analysis, it does not seem that there was any threat to the life of the sergeant who shot the two Palestinians.” Following the debriefing, the IDF Chief of Staff issued a (reprimanding) commander’s notice to the commander of the Samaria brigade, Colonel A., and the commander of the Nahshon regiment also received such a notice. The same goes for G., the deputy company commander. As for A., the shooter, the IDF chief of Staff decided that he would be removed from any command position.

If there had indeed been a threat to the life of the shooter, would all these disciplinary actions have been taken against the entire chain of command? And if there was no threat, and there was a suspicion of an unlawful shooting of innocent persons, why is nobody facing justice? The IDF Chief of Staff, who occasionally approves the publication of operational debriefings, refused to do so in this case.

The investigation: Happy Valentine’s Day

Only after an appeal to the Israeli High Court of Justice by Yesh Din, did the Military Police agree to open an investigation into the killing of the Qawarik cousins. The investigation began in September 2010, around six months after the incident. Another year would pass before the investigators would manage to question A., the shooter. He had been abroad on a long trip. Fewer than 10 people were questioned during the investigation, which was closed in mid January 2014.

The investigators did not bother to confront the soldiers with the fallacies and contradictions in their stories. Numerous contradictions between the testimonies, as well as contradictions between the testimonies and the investigatory findings, remained unresolved. In spite of the reasonable suspicion that some of the soldiers were lying or withholding details known to them, nothing was done to try to find out once and for all what really happened that day.

Just like other investigations which we have reviewed, it appears that the Military Police investigators role in nothing more than stenographers for the soldiers’ statements. Don’t push too hard, don’t ask questions that are too difficult, do not set traps, and certainly do not address more substantial questions: why can a settler with a criminal record stop and detain Palestinians? Under what authority and since when can a settlement security coordinator stop and detain people “because their hands are soft to the touch?”

A. argues that he was stressed out by the cousins speaking Arabic among themselves, because he “did not understand what they were saying.” However, in the same testimony he claims he spoke Arabic to Saleh, and according to the settlement security coordinator, A. interrogated the two using good Arabic. On this point too, the investigators do not press any further. A.’s claim that the cousins’ request to pray at noon was suspect is also unclear, since this is precisely the Muslim prayer time.

Another question: why did A. cock his weapon “quietly?” If he had wanted to show his authority and scare the two, so that they would not try anything again, he surely would have done so in a noticeable manner. That is in fact one reason for cocking a weapon. So why did he do so discreetly? What was he trying to do here? The investigators do not bother to clarify this point.

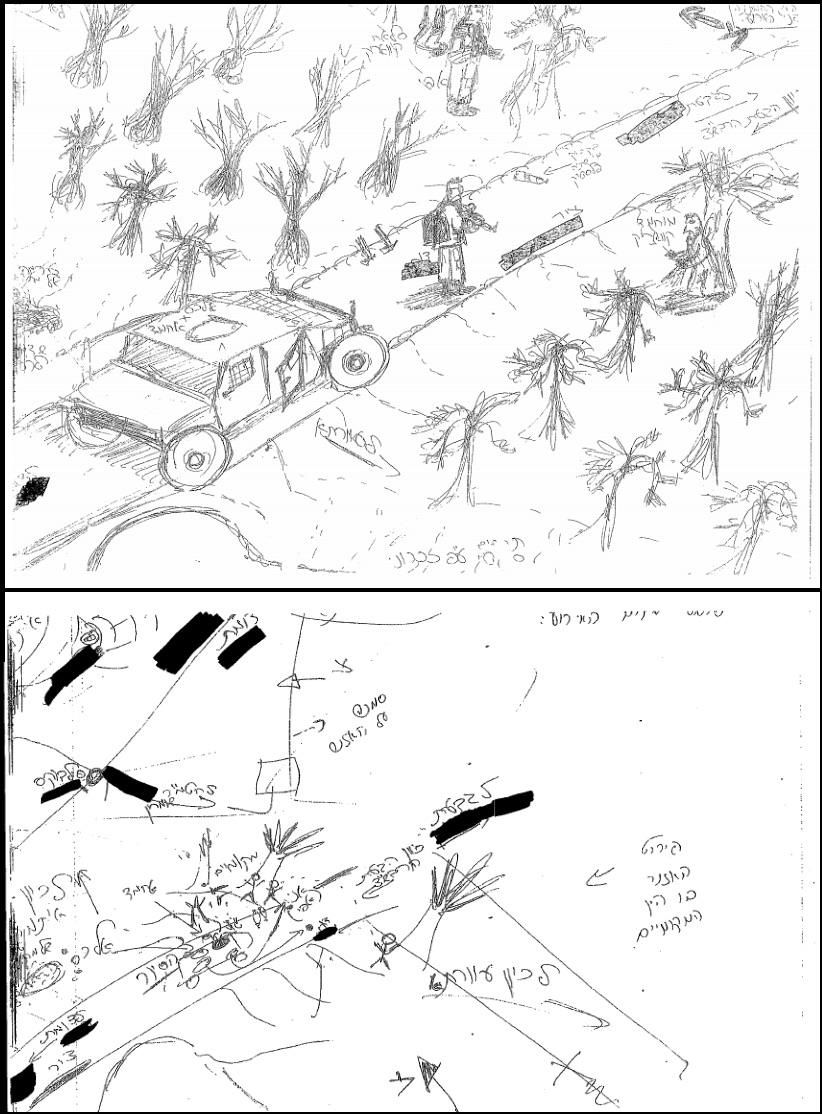

As one can see in the drawings made by the soldiers (above), the jeep is standing on the road, and next to it stands D., who was charged with guarding Muhammad. A. is right next to Saleh, where he also shoots him, while Muhammad is on the other side of the road at a distance of at least 20 meters from his cousin and A. Following the shooting of Saleh, according to D., A. turned around and shot Muhammad from where he was standing. A., who was standing around 10 meters from the road, claims he “went up to the route” in order to Shoot Muhammad.

This contradiction is decisive: did A. notice an attempt to harm D., as he claims, or — since D. was standing on the road next to the jeep — did he run a relatively long distance and, only from there, fire 19 bullets into the second victim’s body? The fourth soldier as well, the one who was sitting in the vehicle, claims he saw A. moving past the vehicle in the direction of the second Palestinian as the latter was already falling down. This critical point — how exactly the shooting of Muhammad took place — remains a mystery, and the investigators do not notice this, or deliberately chose to ignore the issue.

D. claims he did not see or hear anything during the two shooting incidents, even though he was standing 10-15 meters from the scene. Could a normal person argue this and not arouse suspicion, to the extent of not being asked about this even once? According to the Military Police investigators, the answer, apparently, is yes. The same applies to the two other witnesses, who did sit in the car, but apparently had a clear line of vision towards A. and the two arrestees. Failing to press witnesses who were so close to two killing incidents and claim they did not see a thing amounts to negligence — as simple as that.

One can learn something about the atmosphere during the questioning from the final statement of the fourth soldier, the one who made the drawing seen above. That soldier also testified that he had not seen the syringe in question. Finally, when asked whether he had anything to add, he said to the (female) investigator: “Happy Valentine’s Day!”

Another double killing — one day earlier

Commanders are usually not confronted with their negligence during the investigation of acts committed in their area of responsibility, even when the same military unit committed another double killing just one day earlier, and that case had already raised difficult questions. That was the killing of Muhammad Qadous, 15, and Usaid Qadous, 17, who were shot and killed in the village of Iraq Burin. the soldiers and the IDF Spokesperson claimed than that they had been shot with rubber bullets, but the injuries, the entry and exit openings, as well as an X-ray photo of the bullet stuck in Usaid Qadous’ head attests to that being a lie.

It should be no surprise that no indictment was filed as a result of that investigation either. To this day, the case files are still on the desk of the IDF Military Advocate General, even though the soldiers are no longer under the military’s jurisdiction and cannot be indicted by the IDF.

Justice

We will not determine A.’s criminal responsibility, and it is also hard to determine whether a professional investigation would have led to his indictment. It is also hard to say whether an investigation would have led to the indictment of his commanders, who negligently placed the lives of the Qawarik cousins in the hands of a soldier who was clearly unfit for the task. On that day, the commanders also lingered at length while giving contradictory and sloppy orders, blatantly disregarding the time of the two cousins, and later — their lives as well. These are the ones who made A. detain the two at gunpoint, while his frustration and stress levels were growing — until he shot them.

But one thing cannot be disputed: two young men left their house that morning with no wish to hurt anyone, and they never came back. This happened neither during war nor in a combat zone. Just like that. How can anybody accept that?

In our conversations with Atty. Emily Schaeffer Omer-Man of Yesh Din, who represented the family on the criminal side of things, and Atty. Ghada Hliehel, who represents the family in a civil lawsuit, both spoke of the emotional toll that accompanied uncovering the facts of this case. The sense of wrongdoing is further amplified in light of the fact that even the little justice a court could have meted out — has not materialized because of the negligent investigation. We sent detailed questions to the IDF Spokesperson, which decided this case does not merit a response.

Saleh and Muhammad Qawarik are dead, and that cannot be changed. What can, and must change, is the impunity the state gives every soldier involved in de-facto policing activity in the West Bank. An army engaged in policing cannot hide behind the shield of operational conduct. The fact that the state gives weapons to those who are in fact still youths does not give the latter a right to shoot whomever they want without paying for it. Dozens of cases of this type occur every year, and the authorities of the military regime feign innocence. When will this end?

*John Brown is the pseudonym of an Israeli academic and blogger. Noam Rotem is an Israeli activist, high-tech executive and author of the blog o139.org, subtitled “Godwin doesn’t live here any more.” This article was first published in Hebrew on Local Call. Read it here.