Usaid and Muhammed Qadus are shot to death in their own village by a major in the Israeli army who claims he only fired rubber bullets. But the bullets were real, and he admitted to lying and committing forgery to cover up his crime. Instead of being charged with a crime, he is promoted.

By John Brown and Noam Rotem

(Translated from Hebrew by Ofer Neiman)

In the “License to Kill“ series thus far, we have surveyed eight Military Police investigation files regarding the killing of Palestinians by IDF fire. Despite the fact that none of those killed posed a danger to anybody else and despite no lack of evidence pointing to the shooters’ guilt, none of the cases resulted in any indictments. One of the most outrageous cases was the shooting of 20 bullets into the Qawarik cousins and the subsequent whitewashing of the case. In this chapter, we will examine another double killing of young Palestinian men, which took place just one day earlier, by an officer in the same IDF brigade, Kfir, which is also happens to be the unit of the Hebron shooter, Elor Azaria.

After reading the following investigation into the IDF’s own investigation, we believe that you too will find it hard to believe that prosecutors decided not file an indictment for a double murder, or at the very least obstruction of justice. We will show how the shooter, a major in the army, admitted to lying in his testimony, forging documents and trying to tamper with evidence. In spite of all that, the Military Advocate General decided against prosecution. In fact, he continues to serve in the IDF, and has even been promoted to the rank of lieutenant-colonel.

The sequence of events described here is based on the Military Police investigation file, which we have obtained, as well as other testimonies collected by B’Tselem.

The shooting

On the afternoon of Saturday March 20, 2010, a unit from the IDF’s Kfir Brigade entered the West Bank Palestinian village of Iraq Burin on the outskirts of Nablus. The soldiers went there after settlers from the Israeli settlement of Bracha set out toward the village to vandalize and fell Palestinian-owned trees and cause other damage (the army showed up to protect the settlers). From another direction, village youth were gathering, and some of them were throwing stones — which did not pose a threat to the lives of the soldiers, as stated by the battalion commander and other soldiers during their interrogations.

According to the brigade’s operations log, the forces began to retreat at 3:54 p.m. At the same time, Muhammed and Usaid Qadus, both residents of the village, returned home from Nablus via taxi. They were 15 and 17 years old. Since the soldiers were still in the village and Muhammed’s house was unreachable, the taxi dropped them off next to Usaid’s house. According to their friends who were around, Usaid sat down by the entrance to a warehouse near the main road and Muhammed stood next to him.

The deputy battalion commander, Major R., testified that during the soldiers’ retreat, he himself shot two rubber bullets towards the protesters who were standing at a distance of 70 meters (230 feet), and saw that one of them was hit in his arm. In reality, the first shot hit Usaid’s head and the bullet pierced his skull. The second shot hit Muhammed’s chest as he rushed toward Usaid. The shots were fired from a heavy-barrel rifle, preferred by sharpshooters, with an advanced scope. The Palestinian taxi driver, Zakaria, testified in the Military Police investigation that he had dropped off the two a short while earlier, and when he heard the commotion, he came back and took them to the Nablus hospital, where both teens succumbed to their wounds.

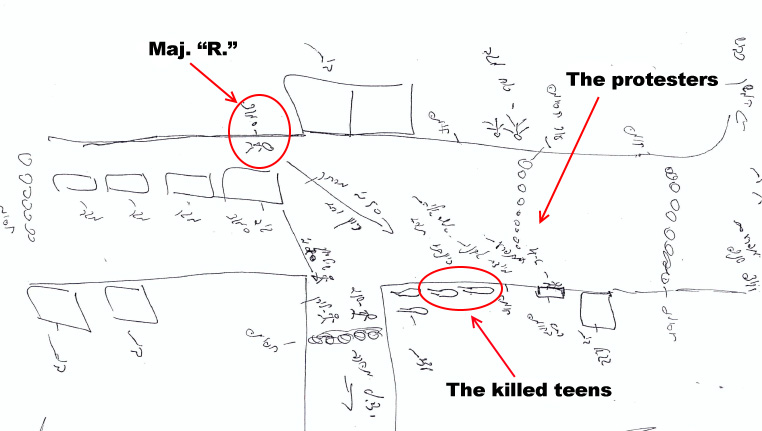

The diagram above was drawn by Maj. R., who claimed the two dead youths were standing next to the rioters (above the lower red circle), and that they even took part in stone-throwing. However, according to testimonies provided by villagers, the two were standing at a distance of at least 50 meters (165 feet) from the stone-throwers, and took no part in the rioting.

The Military Police file states that the drawing was not made to scale. R. claims he shot in the direction of the rioters, but even if the distance was shorter than what the villagers claimed, the probability that the shots were not aimed toward the two slain youths is practically zero.

Considering the distance and the type of weapon used by R. with its advanced scope, hitting the target would have been almost certain. It should be stressed that R. does not claim he shot the two by mistake, but that he purposely shot them with rubber bullets. In this context, it should also be noted that other soldiers and border policemen who were at the scene later said their lives were not in danger. This was also the conclusion of R.’s commanding officer, the battalion commander.

The bullets were not rubber

A year and a half after the incident, Maj. R. (currently a lieutenant colonel) sat in the Military Police’s Sharon-Samaria region interrogation room, and was asked the following:

In the analysis of the investigation case, many facts have been found which attest circumstantially to your culpability in the deaths of the two Palestinians. This includes:

- A medical committee established with the intention of finding any faults or mendacious accounts of the incident, contradictions as to the entrance time and forgery of documents, via-a-vis Lieutenant A.’s account;

- A polygraph test in which you were found to be lying;

- Testimony by D., which explains the lie and forgery regarding the precise dates related to the incident;

- The National Center of Forensic Medicine, which states that the shooting was most probably carried out with live bullets rather than with rubber bullets;

- Numerous pieces of evidence against you, regarding your account during the investigation.

What is your response to this?

The investigation up until that very moment, an investigation in which an IDF officer was forced to confront a big heap of lies and crimes, to some of which he had already admitted, was meticulous in comparison to other investigations we have reviewed in this series. Over 50 witnesses were interviewed, including military experts on matters of arms and munitions, forensic pathologists, physicians, Palestinian witnesses, soldiers in the brigade, Border Police officers who were present at the scene, soldiers in a secret intelligence unit who were also present there on that day, and even an officer with the rank of colonel.

The investigation had produced very grave findings, to some of which R. admitted, and was found to be lying about others in a polygraph test. The web of lies he spun in order to cover up his actions had complicated matters for other soldiers and officers. At one point in the investigation he even claimed that the killing of Usaid and Muhammed Qadus had been “a settling of scores [among Palestinians]”.

It was already evident at the beginning of the investigation who shot the two youths, on the basis of R.’s own admission, but he stuck to his account about shooting two rubber bullets in the direction of the protesters. The problem with that account is that rubber bullets are not supposed to be lethal from the range R. himself claimed he shot them, and numerous physicians and forensic pathologists concluded that the bullets that killed Usaid and Muhammed Qadus were live bullets. This is where things become messy.

First of all, the metal bullet can be seen clearly in an X-ray of Usaid’s head, taken at the Nablus hospital, where he was pronounced dead. The photo was a part of the investigation file. Furthermore, R.’s weapon was incapable of firing rubber bullets, and according to a testimony by the non-commissioned officer in charge of the brigade’s armory, there were no suitable barrel attachments used for firing rubber bullets available at the time; R.’s rifle barrel was heavy (thicker), and the barrel attachments available in the brigade at the time were too narrow, and hence, unsuitable for his weapon.

In addition, R. did not have at his disposal a magazine suitable for shooting rubber bullets. Bullets used with the rubber bullet barrel attachment are supposed to be loaded in a magazine marked with colorful tape. None of the witnesses saw such a magazine that day. According to R., he received the magazine from an officer in the regiment, but the latter has denied R.’s claim, insisting it is a lie.

‘A celebration’

As in any Military Police investigation, unlike civilian police investigations, the file contains no evidence, only interviews. The investigators did not bother to try to collect the bullet shells left at the scene as a result of the shooting, which probably would have refuted R.’s account with high likelihood. However, they turned to several experts within and outside the military in an attempt to understand if there was any chance that the bullets had not been rubber bullets. A medical “expert committee” convened by the Military Police concluded “with very high likelihood” that the shooting was carried out with live bullets, rather than rubber bullets. Weapons experts on behalf of the IDF’s Ordnance Corps concluded that “there is zero likelihood” of rubber munition penetrating a human body from the range from which it was said to have been shot, and that an entry and exit wound (in Muhammed’s case) was completely impossible.

The investigative team interviewed tens of soldiers and police officers who were at the scene. Most of their testimonies are meaningless since they were not close enough to the deputy battalion commander to see the shooting itself. Several testimonies, mainly by R.’s subordinates, support his account as to the presence of a rubber bullet rifle barrel attachment, before he got out of the vehicle. These testimonies, too, are full of contradictions. For example, R. himself says he had not unloaded the weapon, but First Sergeant Y. says R. had done so inside the vehicle (in violations of the procedures). Corporal L. claims he did not hear any shot by R., in spite of being close to him, which contradicts the testimony of R. himself, and more. Remember this testimony by Corporal L. We shall get back to it.

During one of the questioning sessions, Maj. R. is asked to reconstruct the shooting precisely, which he does in detail. However, he skips one important stage in the process: in order to shoot rubber bullets through a barrel attachment, one has to load the weapon with blank bullets, (consisting of a casing and gun powder only, without the slug itself). Blanks create the gas pressure necessary to propel the rubber-coated munition out of the barrel and a long distance toward the target, but the pressure does not suffice to trigger the rifle’s automatic loading mechanism to chamber the next bullet, which usually has to be done manually. R. states that he fired two rounds, but he does not mention any reloading in between. He recounts the insertion of the rubber bullets, the shooting and then another insertion and another additional shooting. The Military Police investigators, who are apparently unfamiliar with the material, did not bother to ask him about this.

S., a border policeman who stood next to R. during the shooting, told investigators in a very detailed testimony that he could recall R. shooting with his weapon which lacked the barrel attachment for shooting rubber bullets, something which the investigators did not bother to follow up on. A soldier who served under R.’s command was asked what kind of ammunition R. had shot and responded by saying “M16.” It’s not clear whether he meant live ammunition or he was trying to dodge the question, since M16 is a type of rifle and not a type of ammunition. Here too, the investigators did not try to ask further questions.

S. also recounts an incident that took place the following day at the gate of the base where the unit was stationed, according to what he heard from a fellow border police officer. Corporal L., the one who later testified that he had heard no shooting, had boasted that in the Iraq Burin incident there was a “celebration” — a term used to describe the emptying of a magazine full of live bullets, according to L. The investigators managed to find the officer. The latter identified L. correctly in a photo lineup, and also provided additional details on him which, distinctly identifying him, such as the date he was drafted into the army and the training school he attended, which was different from that of his peers in the unit.

The entire body of testimonies leads one to the conclusion: that the shooting was carried out with live bullets rather than rubber bullets. From R.’s later interrogation, as can be seen in the quote cited above, it seems that the Military Police investigators also saw things that way. R. too must have known that he fired live bullets, and that’s why he took measures to conceal that fact.

Weapon swapping, forgery

Around six months after the double killing, D., a non-commissioned officer in charge of the brigade’s armory, approached the battalion commander and told him he suspected R. had forged the armory forms from the day of the incident. According to his testimony to Military Police, on the day Usaid and Muhammed Qadus died, around 5:00 p.m., an officer by the name of A. asked for the keys to the armory, claiming there was an urgent matter to be addressed. On Sunday, a soldier serving in the armory arrived, and found out the armory log stated that the place had been opened on Thursday, two days before the shooting. This soldier had been present in the unit that Thursday, and he had the only key to it. Therefore, he was able to testify that it was impossible for the armory to have be opened on that day without his knowledge.

The aforementioned officer, A., choked under pressure in his interrogation, admitting that he forged the armory forms. He claimed he trusted R. — the shooter — “without thinking twice,” based on the latter being his commander. He also agreed to incriminate R., and get him to admit to committing the forgery while investigators recorded (this was not necessary ultimately, since R. admitted to the forgery in the final stages of his interrogation). According to his account, which is substantiated by phone logs, R. had asked him to swap their personal weapons on the Saturday following the incident, but also asked him to back-date the log of the swap to Thursday, that is, two days before the shooting.

Two motives may be ascribed to this swap. The first would be to ensure the weapon in R.’s possession prior to the incident, according to registration papers, would not match the bullets in the ballistic test, if and when a bullet was obtained. The second motive is that, as stated previously, it was impossible to fit R.’s original weapon with a rubber bullet barrel attachment, but A.’s weapon could have been fitted with one. Therefore, without the swap, R.’s account would have fallen apart easily.

The battalion commander’s explanation

“If there was live shooting, they will have to conceal it”, the battalion commander told investigators as a possible explanation for why R. swapped out his weapon, and then added a second possibility, “that there was a problem with [R.’s] weapon.” This is not very likely, since in that case, R. would have returned the weapon to the armory, rather than letting his subordinate, A., carry a faulty weapon.

The case is similar with regards to the magazine, which purportedly contained blank bullets for firing rubber-coated munitions. R. claims he had received it from A. before he went to the village of Iraq Burin. A. denies this. R.’s soldiers, who were likely with him when he received the magazine, cannot recall it either. R. was found to be lying in a lie-detector test.

Considering all of that evidence and testimony, one cannot help but conclude that R.’s account is completely mendacious. At some stage during the interrogation, he simply refused to respond to any more questions, when his lies were already obvious.

A cover-up?

So far, we have cited only data from the Military Investigation investigation itself. All the data presented here was available to the Military Advocate General, which decided to close the case.

Incidentally, Usaid’s mother recounts that around one month after the killing of her son, a man dressed in plainclothes and who spoke Arabic well came to her house. He did not disclose his name but said he was from “a compensation institute.” She says he behaved strangely, as if he was trying to record her. Among other things, he narrated the arrival of everybody who came into the room, asked her to come closer so that he could hear better, asked that others not be present in the room, and more.

This person, according to the mother, insisted on asking her about her son’s affiliation with a terror organization, asked who paid for his freshly dug grave, who paid for the food served during the mourning period, whether Usaid and Muhammed had thrown Molotov cocktails at soldiers, and similar questions.

After he finished, he went to several of the neighbors’ homes, asked similar questions, and even tried to get them to sign papers.

A promotion

In February 2015 the IDF’s Military Advocate General decided to close the case against Maj. R., now Lt.-Gen. R., after more than three years since the last investigative actions had been taken. The reasons given to B’Tselem, which represented the family of the boys, are puzzling, albeit unsurprising considering the MAG’s record when it comes to (not) indicting rogue soldiers and officers.

Maj. Harel Weinberg, the Deputy MAG for Operational Affairs, wrote:

There was insufficient evidence to conclude, with the level [of certainty] required in criminal law, that live shooting had been carried out during the incident, or that the shooting which was carried out by the officer had brought about the deaths of the deceased. Furthermore, since according to the testimonies there was a threat to the lives [of the soldiers], even if R. had fired live ammunition, one cannot ascribe to him the offense of firing in violations of military regulations.

As to the lies, forgery and witness tampering, obstruction of an investigation, the concoction of a patently false cover-up and the generally shameful conduct, Maj. Weinberg stated that the officer has been “reprimanded,” but that this did not suffice to take a fresh look at the investigation of the shooting case.

It should be noted that the battalion commander affirmed that the soldiers had not been in a life-threatening situation, and this was corroborated by other soldiers and police officers who had been at the scene. The legal firing of live ammunition necessitates one of two things in the IDF: a life-threatening situation, and that was not the case; or a request for special authorization from the brigade commander. Such an authorization was neither asked for nor granted, and the two slain youths did not even take part in the riots, according to most testimonies.

As stated already, R. has since been promoted, and he now serves as a senior commanding officer and in an educational position.

We usually do not deal with the motives leading to killing incidents, but in this case there is what appears to be relevant material. R. has posted vulgar and offensive comments about Palestinians on his Facebook page in the past. For example, in July 2014, he wrote that “in Gaza there are two kinds of gnats, and both go up to the sky when they meet the IDF.” He also liked comments stating that Arabs were primitive, as well as comments calling leftists the Hebrew equivalent of “kike.”

This ideology may have played a role in the shooting. Perhaps not. In any case, it is a blood-curdling case. The first of two double-killing incidents in two days by the Kfir brigade. The fact that neither killing resulted in an indictment demonstrates that the IDF’s investigation mechanism whitewashes the killing of Palestinians, and grants its soldiers, at least in practice, a license to kill.

The IDF Spokesperson issued the following response:

On March 20, 2010, a violent riot took place on the outskirts of the village of Iraq Burin. Following claims that Muhammed and Usaid Qadus were shot by an IDF soldier, a comprehensive military police investigation was immediately initiated, to clarify the circumstances of this incident. According to the findings of this investigation, the rioters threw stones [massively] at an IDF force, in a way which posed a real threat to the soldiers. In response, the commander of the force shot in the direction of the rioters.

According to the findings of the investigation, it was impossible to rule out the officer’s claim that the shooting had been carried out with rubber bullets only, and it was impossible to conclude that the shooting led to the death of the deceased, due to a refusal on the part of their families to conduct an autopsy at the time. Therefore, it was decided to close the case.

As to the claims regarding the commander’s conduct following the incident, a disciplinary procedure took place in this matter.

We asked the IDF Spokesperson to describe the “disciplinary procedure” regarding the forgery and lying, including and whether this procedure involved some form of punishment. A response to this follow-up question had not been received at the time of publication. The Jerusalem Magistrate’s Court is currently hearing a wrongful death lawsuit filed by the families of the two slain youths against the State. They are represented by Adv. Amjad Atawna.

*John Brown is the pseudonym of an Israeli academic and blogger. Noam Rotem is an Israeli activist and high-tech executive. This article was first published in Hebrew on Local Call, where they are both bloggers. Read it here.