Can an American politician who was born to Jewish parents just be an American politician who happens to be Jewish? Is Israel becoming less important in American politics?

NEW YORK — Bernie Sanders, the senator from Vermont, won the Democratic primary in the state of New Hampshire on Tuesday night. Sanders, who identifies as a social democrat, is Jewish.

But when he spoke about his background in his victory speech he mentioned only that he was the son of Polish immigrants who were poor and little-educated, making it sound as though they might have been eating kielbasa and pierogi for Sunday lunch instead of challah and tsimmes for Friday night dinner.

He highlighted his own success as an illustration of the national narrative that Sanders called “the promise of America” — the idea that one should be able to achieve one’s goals based on hard work and merit.

“My friends,” said Sanders,

I am the son of a Polish immigrant who came to this country speaking no English and having no money. My father worked every day of his life and he never made a whole lot.

My mom and dad and brother and I lived in a three and a half room rent controlled apartment in Brooklyn, New York. My mother, who died at a young age always dreamed of moving out of that apartment, getting a home of her own, but she never realized that dream. The truth is that neither one of my parents could ever have dreamed that I would be here tonight standing before you as a candidate for president of the United States.

This is the promise of America and this is the promise we must keep alive for future generations.

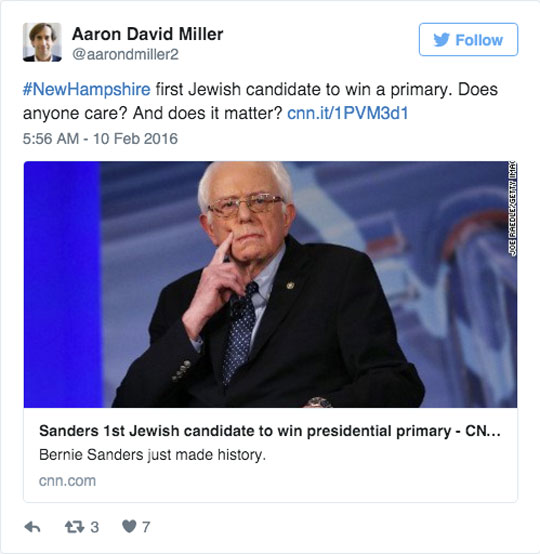

Several Jewish observers on social media were unhappy at Sanders’ failure to emphasize that his parents were Jews, and that he is now the first Jewish American to win a Democratic primary. (Barry Goldwater, the Republican nominee in the 1964 election, had a Jewish father but was raised Episcopalian, although he acknowledged his Jewish heritage.)

Sanders has never denied that he is Jewish. Nor could he, even if he wanted to, given that he bears an uncanny resemblance to practically every other 70-something Jewish man who lives on Manhattan’s Upper West Side.

He has spoken about spending a few months volunteering on a kibbutz during the mid 1960s, although since entering the presidential race he has tantalized journalists by refusing to name the kibbutz. The information became a bit of a holy grail for Jewish journalists, until a Haaretz reporter finally discovered it last week in a 26 year-old interview Sanders gave to the paper.

Sanders married the Jewish American woman who traveled with him to the kibbutz, but they did not have children and divorced in 1966, less than two years into the marriage. He has been with his second wife since 1988; she is not Jewish.

Sanders is also not the kind of Jewish legislator who advocates for tribal causes. He does not, for example, give speeches or make appearances at events on behalf of Jewish federations or Israel advocacy NGOs like AIPAC. Vermont, the state he represents in the senate, does not have a significant Jewish population — although my friend Allison Kaplan Sommer, the Haaretz columnist, discovered that one of his closest friends and advisors is an Orthodox Jew who teaches at the University of Vermont.

Most recently, Sanders made self-deprecating Jewish jokes in a Saturday Night Live skit with Larry David, whose parody of Sanders is so accurate that many claim it has become a contemporary comedic trope (Sanders comes in at 2:15 in the video embedded below).

American Jews vote overwhelmingly for the Democratic party, and plenty of them support Bernie Sanders. But their affinity for the candidate is based on his political views, which are primarily about social justice and and social welfare. His single mention of the Middle East in his New Hampshire speech was a reference to the group that calls itself Islamic State, or ISIS, and the need to destroy them without sending American soldiers to fight another war there. He did not mention Israel at all. So Jews who are on the fence about Bernie are wondering if they should be proud that one of their own could be president, or irritated that he’s not rushing to embrace the tribe.

Can an American politician who was born to Jewish parents just be an American politician who happens to be Jewish? In the country that considers the right to re-invent oneself a defining value, surely that is Sanders’ right. It’s not as though he’s pretending to be something he’s not. He simply doesn’t seem to feel that his Jewishness is an important factor in his political views.

On the other hand, a Jewish American who is deeply committed to the values of social justice, especially one with a distinctive Brooklyn accent, is in very much a “type” that most Jewish Americans identify with deeply. Often called “red diaper babies” for the social-democratic values they were raised on, they played prominent roles in the major social justice causes of the 1960s, most notably in the civil rights movement. The collective memory of their involvement in social justice causes is a powerful chapter in the Jewish American narrative, often portrayed in Hollywood films. The liberal branches of Judaism in the United States even identify social justice as a Jewish value called “tikkun olam,” or healing the world. Which is why so many American Jews are convinced they remember an Uncle Sheldon who looked and sounded just like Bernie, and who dominated political conversations at their Passover seders or their Friday night dinner tables. You can see the female equivalent portrayed by “Aunt May,” the secular socialist schoolteacher in the seder scene of Woody Allen’s Crimes and Misdemeanors.

Perhaps the most significant aspect of Sanders’ candidacy is, as he has said on several occasions, that he has shown it’s possible to raise money for a presidential campaign without taking money from the big financial institutions or the oligarchs. But he has also shown that a candidate need not curry favor either with donors or with the electorate by visiting or mentioning Israel. Do voters not care about Israel anymore? We’ve hardly heard about it in this campaign.

Compare this year’s primaries to the 2008 campaign, when then-Senator Obama felt compelled to visit Israel and be photographed placing a note in a crevice of the Western Wall, even before he was nominated as his party’s candidate for the presidency. And remember the unseemly one-upmanship between Biden and Republican candidates over who was really a BFF of Bibi’s? This time ’round, no candidate is mentioning her or his friendship with the Israeli prime minister. In fact, they’re not talking about Israel much at all. Donald Trump even managed to get away with making borderline anti Semitic jokes during his speech at the Republican Jewish Coalition — and he still won his party’s primary in New Hampshire on Tuesday night.

And while it’s very common to encounter Jewish Americans who espouse deeply liberal social views but swing disconcertingly to the right on Israel, the interesting thing about these “Progressive Except for Palestine” (PEP) Jews is that they do not vote for candidates based on their views on Israel — which is why Bernie Sanders can appeal to Jewish voters without mentioning his affection for Israel or rushing off to Jerusalem to give Bibi a hug.

Is it important that the Democratic party’s candidate for president in 2016 might be a Jew for the first time? In historical terms, of course it is. But I don’t think its significance is that the age of discrimination against Jews has passed, any more than the age of discrimination against African Americans passed with the election of Barack Obama.

Bernie hasn’t tested his secular social democratic views in the Bible belt states yet. But in terms of the impact Israel policy has on the U.S. electorate, what is significant is the fact that Sanders managed to trounce Hillary Clinton in New Hampshire without once mentioning the only democratic state in the Middle East ™, Golda or the right to self defense against terrorists. Perhaps what we are seeing is the decline of Israel as a major factor in U.S. domestic politics.