By Anna Momigliano

It has been noted that this is the first war declared on Twitter. At this point I find myself wondering if this might be as well the first war lost on Twitter.

Don’t get me wrong, I am well aware that there are thousands of people on both sides in fear of their lives and that the use of social media is the least of their concerns. Nor do I think that the “media war” is even remotely as relevant as the actual conflict that is raging over Israel and the Gaza Strip. Yet, as someone who cares for Israel and has been following its online communication for quite a while, I can’t help but ask myself: what went wrong with online hasbara?

Since its very beginning, the State of Israel understood that the “battle for hearts and minds” was one of the keys to its survival — the very term “hasbara,” roughly translating into “explanation,” implying that Israel felt compelled to explain its existence to the rest of the world, and was willing to do so in the most effective way. Eventually the world assumed a derogatory meaning, especially in liberal circles; it became equated with propaganda (usually, but not always, right wing propaganda). To some, the difference is subtle: “While propaganda is invariably a mixture of half-truths, fabrications and downright lies, hasbara generally employs a highly selective version of true facts,” wrote earlier this year Anshel Pfeffer on Haaretz. Pfeffer argued that hasbara is “one of the basic tenets of 21st century Zionism” and that it is “a total fallacy.”

Yet, no matter whether you see it as crass propaganda or as a righteous tool to explain Israel to the rest of the world, one thing can be said about hasbara: for the most part, it has worked. Whether it’s angry readers flooding a newspaper with letters because they they feel its coverage of the Middle East is biased, pro-Israel organizations setting up events in campuses, or bloggers doing their best to put a human face on the country, the “hasbaristas” have succeeded pretty well in sending the message that messing with Israel isn’t such a good idea.

Then came social media.

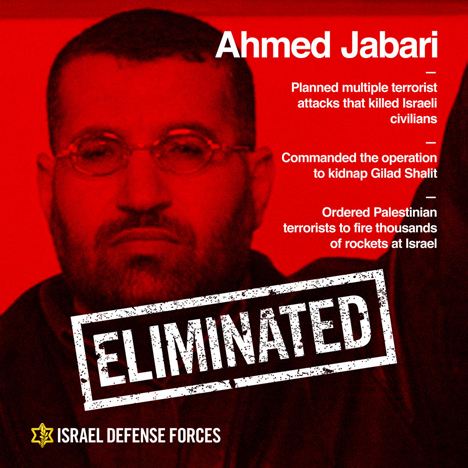

Now, here we’re entering the realm of subjectivity. But my impression is that the government and the IDF haven’t done such a good job in defending Israel’s image, especially on the Internet. And, by the way, I am not the only one to see it this way. Some may find it ironic, given all the efforts they have invested in using Twitter and YouTube since this military campaign began. The IDF spokespeople have basically live tweeted the conflict; they also posted a series of hasbara-ish videos in the army’s official YouTube account, such as “How Does the IDF Minimize Harm to Palestinian Civilians in Gaza?” while at the same time releasing footage of airstrikes, including the assassination of Hamas military leader Ahmed Jaabari. Not to mention the intended dissemination of the meme “Ahmed Jaabari – Eliminated”

The thing is, this type of campaign does not really work. Not if your aim is improving Israel’s image. Not if you’re dealing with Web 2.0, where communication works horizontally. Not in a post-Arab Spring, post-“Innocence of the Muslims” world.

One of the greatest communication weaknesses of the pro-Israel camp consists of having failed to understand how horizontal social media work. Bragging about the “elimination” of an enemy might not be the best choice of PR to begin with, but it does bring an instantaneous backlash in an environment such as Twitter, where users all around the world are quick to fire back, pointing at you as a warmonger.

On Twitter a reply can have the same weight of the original tweet — which, among other things, means that numbers matter. Yet the pro-Israel camp, traditionally relying on a relatively small number of very active netizens, seems still used to a blog-like style of communication, where comments are nothing more than background noise. On the other hand the pro-Palestinian camp, galvanized by the social media activism surrounding the Arab revolutions, seems much more at ease with a horizontal style of communication – not to mention the fact that it can count on a much larger base.

What struck me the most, however, is how the IDF appears to have underestimated the current self-consciousness of social media companies. Only a few months after the “Innocence of Muslim” affair (when a 14-minute-long, ludicrously low quality video claiming to be the trailer of a movie was posted on YouTube by an obscure user, causing world wide unrest), the last thing Twitter and YouTube want is to be dragged into a war.

A few hours after the IDF posted on its account the footage of the “pinpoint elimination” of Ahmed Jabari, YouTube removed it, citing a breach of the terms of agreement. Well, only the English version of the video, which was likely to get more international viewers, was removed. Interestingly enough, the Hebrew version remained online.

Similarly, Twitter has briefly suspended one of the IDF official accounts. It has been speculated that the reason behind that was a supposed breach of the rule that prohibits “direct, specific threats of violence against others” on the platform. Some have pointed out that in no way has the IDF issued “specific threats of violence,” not even as it tweeted “We recommend that no Hamas operatives, whether low level or senior leaders, show their faces above ground in the days ahead” – although the subtext was clear, technically speaking, it was a warning, not a threat. One could argue, moreover, that if Twitter were to suspend all accounts that issue veiled threats… well, there would be no Twitter anymore. But, again, here the subtext was clear: Twitter doesn’t like to be dragged into a war.

Perhaps the IDF has understood the power of social media. But it hasn’t understood how self-conscious social media is about its own power.

Anna Momigliano is an Italian journalist focusing on the Middle East and new media. She edits the magazine Studio and authored Karma Kosher, a book about Israeli youth.

Click here for more +972 coverage on the Israel-Gaza conflict.