Citing potential damage to Israel’s foreign relations, the Supreme Court rejects a petition calling to reveal details of the government’s arms exports to the Serbian army during the Bosnian genocide.

By John Brown* (Translated by Tal Haran)

Israel’s Supreme Court last month rejected a petition to reveal details of Israeli defense exports to the former Yugoslavia during the genocide in Bosnia in the 1990s. The court ruled that exposing Israeli involvement in genocide would damage the country’s foreign relations to such an extent that it would outweigh the public interest in knowing that information, and the possible prosecution of those involved.

The petitioners, Attorney Itay Mack and Professor Yair Oron, presented the court with concrete evidence of Israeli defense exports to Serbian forces at the time, including training as well as ammunition and rifles. Among other things, they presented the personal journal of General Ratko Mladić, currently on trial at the International Court of Justice for committing war crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide. Mladić’s journal explicitly mentions Serbia’s ample arms ties with Israel at the time.

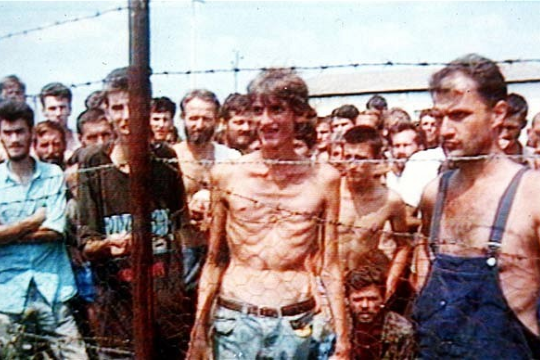

The exports took place long after the UN Security Council placed an arms embargo on various parts of the former Yugoslavia, and after the publication of a series of testimonies exposing genocide and the creation of concentration camps.

The Israeli State Attorney’s reply and the court’s rejection of the petition are a de facto admission by Israel that it cooperated with the Bosnian genocide: if the government had nothing to hide, the documents under discussion would not pose any threat to foreign relations.

The most horrific acts of cruelty since the Holocaust

Between 1991 and 1995 the former Yugoslavia shattered, going from a multi-national republic to an assemblage of nations fighting each other in a bloody civil war that included massacres and ultimately genocide.

The Serbs waged war against Croatia from 1991-1992, and against Bosnia from 1992-1995. In both wars the Serbs committed genocide and ethnic cleansing of Muslims in the areas they occupied, leading to the deaths of 250,000 people. Tens of thousands of others were wounded and starved, a multitude of women were raped, and many people were incarcerated in concentration camps. Other parties to the conflict also committed war crimes, but the petition focuses on Israel’s collaboration with the Serbian forces. The horrendously cruel acts in Yugoslavia were the worst Europe had seen since the Holocaust.

One of the most notorious massacres was perpetrated by soldiers serving under Serbian General Ratko Mladić around the city of Srebrenica in July 1995. Serbian forces commanded by the general murdered about 8,000 Bosnians and buried them in mass graves in the course of a campaign of ethnic cleansing they were waging against Muslims in the area. Although the city was supposed to be under UN protection, when the massacre began UN troops did not intervene. Mladić was extradited to the International Court of Justice at The Hague in 2012, and is still on trial.

At the time, prominent Jewish organizations were calling for an immediate end to the genocide and shutting down the death camps. Not so the State of Israel. Outwardly it condemned the massacre, but behind the scenes was supplying weapons to the perpetrators and training their troops.

Attorney Mack and Professor Oron have gathered numerous testimonies about the Israeli arms supply to Serbia, which they presented in their petition. They provided evidence of such exports taking place long after the UN Security Council embargo went into effect in September 1991. The testimonies have been crossed-checked and are brought here as they were presented in the petition, with necessary abbreviations.

In 1992 a former senior official of the Serb Ministry of Defense published a book, The Serbian Army, in which she wrote about the arms deal between Israel and Serbia, signed about a month after the embargo: “One of the largest deals was made in October 1991. For obvious reasons, the deal with the Jews was not made public at the time.”

An Israeli who volunteered in a humanitarian organization in Bosnia at the time testified that in 1994 a UN officer asked him to look at the remains of 120 mm shell — with Hebrew writing on it — that exploded on the landing strip of the Sarajevo airfield. He also testified that he saw Serbs moving around in Bosnia carrying Uzi guns made in Israel.

In 1995 it was reported that Israeli arms dealers in collaboration with the French closed a deal to supply Serbia with LAW missiles. According to reports from 1992, a delegation of the Israeli Ministry of Defense came to Belgrade and signed an agreement to supply shells.

The same General Mladić who is now being prosecuted for war crimes and genocide, wrote in his journal that “from Israel — they proposed joint struggle against Islamist extremists. They offered to train our men in Greece and a free supply of sniper rifles.” A report prepared at the request of the Dutch government on the investigation of the Srebrenica events contains the following: “Belgrade considered Israel, Russia and Greece its best friends. In autumn 1991 Serbia closed a secret arms deal with Israel.”

In 1995 it was reported that Israeli arms dealers supplied weapons to VRS — the army of Republika Srpska, the Bosnian Serb Army. This supply must have been made with the knowledge of the Israeli government.

The Serbs were not the only party in this war to which the Israeli arms dealers tried to sell weapons. According to reports, there was also an attempt to make a deal with the anti-Semitic Croatian regime, which eventually fell through. The petition also presented reports by human rights activists about Israelis training the Serb army, and that the arms deal with the Serbs enabled Jews to leave Sarajevo, which was under siege.

While all of this was taking place in relative secrecy, at the public level the government of Israel lamely expressed its misgivings about the situation, as if this were some force majeure and not a manmade slaughter. In July 1994, then-Chairman of the Israeli Knesset’s Foreign Relations and Defense Committee MK Ori Or visited Belgrade and said: “Our memory is alive. We know what it means to live with boycotts. Every UN resolution against us has been taken with a two-thirds majority.” That year, Vice President of the US at the time, Al Gore, summoned the Israeli ambassador and warned Israel to desist from this cooperation.

Incidentally, in 2013 Israel had no problem extraditing to Bosnia-Herzegovina a citizen who immigrated to Israel seven years earlier and was wanted for suspicion of involvement in a massacre in Bosnia in 1995. In other words, at some point the state itself recognized the severity of the issue.

The Supreme Court in the service of war crimes

The Supreme Court session on the state’s reply to the petition was held ex parte, i.e. the petitioners weren’t allowed to hear it. Justices Danziger, Mazouz and Fogelman rejected the petition and accepted the state’s position that revealing the details of Israeli defense exports to Serbia during the genocide would damage Israel’s foreign relations and security, and that this potential damage exceeds the public’s interest in exposing what happened.

This ruling is dangerous for several reasons. Firstly, the court’s acceptance of the state’s certainty in how much damage would be caused to Israel’s foreign relations is perplexing. Earlier this year, the same Supreme Court rejected a similar claim regarding defense exports during the Rwandan genocide, yet a month later the state itself declared that the exports were halted six days after the killing started. If even the state does not see any harm in revealing — at least partially — this information regarding Rwanda, why was a sweeping gag imposed on the subject a month prior? Why did the Supreme Court justices overlook this deception, even refusing to accept it as evidence as the petitioners requested? After all, the state has obviously exaggerated in its claim that this information would be damaging to foreign relations.

Secondly, it is very much in the public’s interest to expose the state’s involvement in genocide, including through arms dealers, particularly as a state that was founded upon the devastation of its people following the Holocaust. It was for this reason that Israel was, for example, willing to disregard Argentina’s sovereignty when it kidnapped Eichmann and brought him to trial on its own soil. It is in the interest not only of Israelis, but also of those who were victims of the Holocaust. When the court considers war crimes, it is only proper for it to consider their interest as well.

When the court rules in cases of genocide that damage to state security — which remains entirely unproven — overrides the pursuit of justice for the victims of such crimes, it is sending a clear message: that the state’s right to security, whether real or imaginary, is absolute, and takes precedence over the rights of its citizens and others.

The Supreme Court’s ruling might lead one to conclude that the greater the crime, the easier it is to conceal. The more arms sold and the more genocide perpetrators trained, the greater the damage to the state’s foreign relations and security should such crimes be exposed, and the weight of such supposed damage will necessarily override the public interest. This is unacceptable. It turns the judges — as the petitioners have put it — into accomplices. The justices thus also make an unwitting Israeli public complicit in war crimes, and deny them the democratic right to conduct the relevant discussion.

The state faces a series of similar requests regarding its collaboration with the murderers of the Argentinian Junta, Pinochet’s regime in Chile, and Sri Lanka. Attorney Mack intends to present additional cases by the end of this year. Even if it is in the state’s interest to reject these petitions, the Supreme Court must stop helping to conceal these crimes — if not for the sake of prosecuting perpetrators of past atrocities, at least in order to put a stop to them in our time.

*John Brown is the pseudonym of an Israeli academic and a blogger. This story first appeared in Hebrew on Local Call, where he is a blogger. Read it here.