While many remember Supreme Court Justice Edmund Levy, who passed earlier this month, for concluding that there is no occupation of the West Bank, Ofer Sitbon says we must see Levy as an activist judge with a strong sense of justice for the underprivileged.

By Ofer Sitbon

Everyone had their own Edmund Levy. Since passing away at the age of 72 two weeks ago, the former Supreme Court justice has received myriad obituaries highlighting his extraordinary judicial personality. There were those who longingly emphasized his ruling regarding Israel’s disengagement from Gaza, in which he wrote unprecedented political lines in Israel’s legal history, including: “each one of us is commanded to see himself as if the sword of the evacuation was swung on his neck” and “the right of Jews to settle in Judea, Samaria and Gaza draws its power from the same source that gave the Jews the right to settle in Nahariya, Ashdod, Ashkelon, Ramle and Lod.” Levy is especially remembered for heading a Netanyahu-appointed committee that released a report stating that the West Bank is not “occupied territory,” and therefore the establishment of settlements there does not breach international law.

Along with the Revisionist side of the man who previously served as deputy mayor of Ramle on behalf of the Likud, others praised Levy for being an “outsider” justice who was never a member of the “Rehavia gang” (a group of liberal justices that controlled the Supreme Court in the 90’s and 00’s). In his eulogy, Attorney Avigdor Feldman stuck primarily to Levy’s courageous ruling about the unconstitutionality of the Citizenship Law, which banned family unification between Israeli Arabs and their Palestinian spouses who live in the occupied territories. In his ruling, Levy wrote remarkable lines such as “the Citizenship Law threatens to break down the wall of the “Jewish and democratic state,” whose robustness has protected it until now.” The effect of the law remains strong – the damage still echoes today. Its legislation is a seminal event in the history of Israeli democracy.

Furthermore, Professor Aeyal Gross eulogized the activist justice who, alongside his rightist activism, wrote also inspiring social-democratic rulings – such as the cancellation of the binding of migrant workers to their employers; and especially his resounding minority opinion about the cutting of income support (the “Mehuyavot ruling”), and echoed the views of Nobel laureate Amartya Sen:

‘Poverty traps’ are not generated only as a result of welfare benefits. Such an approach is wrong and misleading. Poverty traps are also generated – perhaps even primarily – as a result of many other factors: poverty traps are created when not everyone enjoys equal access to education and higher education; poverty traps are created when not everyone enjoys equal access to basic infrastructures; poverty traps are created when labor laws are not enforced, when the freedom of association of workers is not protected and illegal and wrongful employment practices become a common sight; poverty traps are created when unjustified discrimination exists, fueling feelings of alienation and deprivation.

We can only hope that one day they will be adopted by an Israeli politician.

One aspect that these obituaries have mostly ignored was Levy’s Mizrahi identity. Although he was born in Iraq, grew up in a ma’abara (a transitional camp established by the state, usually for Jewish refugees or immigrants from the Muslim world, as well as for Holocaust survivors) and was appointed to the Supreme Court by Minister Meir Shitrit to fill the infamous “Mizrahi seat” (in Levy’s case, it was also the “religious seat”), Levy hardly expressed his Mizrahi identity in his rulings. In the most prominent case in which he had the opportunity to write a “landmark ruling” regarding ethnic discrimination – the shocking incident of the separation barrier erected between ultra-Orthodox Mizrahi and Ashkenazi girls in the “Beit Yaakov” school in Emmanuel – he was content with writing a sparse ruling that emphasized only the religious discrimination against “Sepharadic” girls. By doing so, Levy accepting the narrative of the school’s principals, which stated that the separation had nothing to do with the girls’ ethnic origins.

Thus, Justice Levy – consciously or not – unfortunately adopted what Prof. Yifat Biton calls the Israeli courts’ “dynamics of denial” in regard to the discrimination of Mizrahis in Israel, despite the existence of clear “discrimination resulting” against them. To use the well-known distinction made by political philosopher Nancy Fraser, Justice Levy may have gone further than any other justice who has served in the Supreme Court regarding the issue of resource distribution, but did not make the extra step concerning recognition.

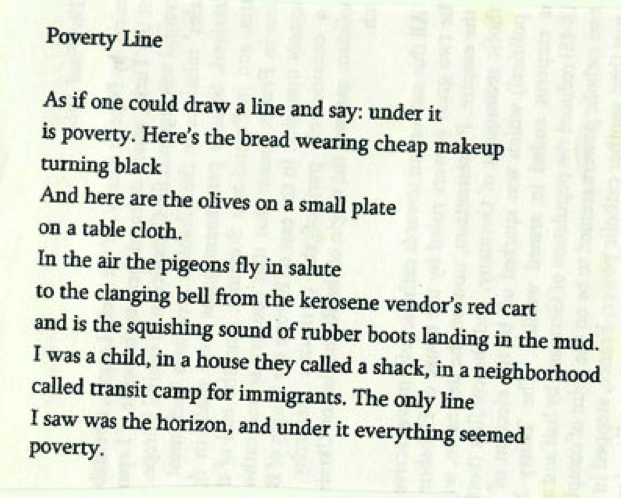

How great would it be if we had more judges who understood Ronny Someck’s poem “Poverty Line,” which opened Levy’s “Mehuyavot ruling”:

Dr. Ofer Sitbon is the director of Corporate Responsibility Institute in the College of Law & Business and a senior fellow in Shaharit – a think-tank for new politics. This article was first published in Hebrew on the Haokets website.

Related:

Panel appointed by Netanyahu concludes: There is no occupation

PHOTOS: A decade on, Citizenship Law still denies Palestinians their rights