A friend asked me to help him sort his books. He’s not a young chap anymore, and has accumulated quite a number of books over his 80 years. Many of them were simply piled on the floor of his study; others were decked in on the shelves in multiple rows, the front ones obstructing access to the ones behind since the early 1960s.

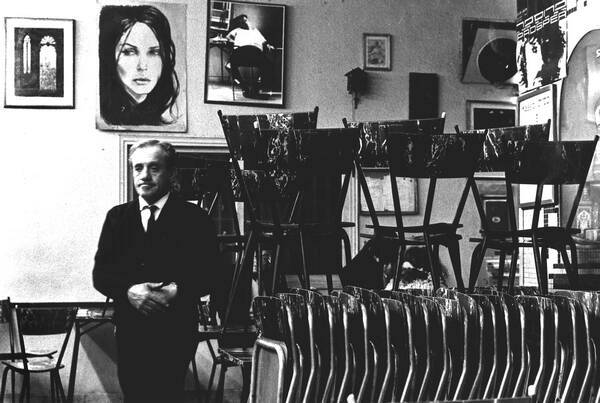

This friend is no boring chap. I’m honored to have been of help to Yoram Kaniuk, my favorite Hebrew author and a man who’s lived several lives in one. While going through his books we found an edition of Chaim Nachman Bialik’s complete works, signed by the national poet himself. Bialik was Kaniuk’s godfather and held him on his knees during his brit milah in 1930. We also found books with dedications by Dahn Ben-Amotz, the king of Tel Aviv’s bohemia in the 1960s, and of other legends. Kaniuk has been in the very core of several arts scene in this city, and not in it alone.

I received a few gifts for my efforts. Most were books, of course, the highlight being a vintage three volume edition of Alter Druyanov’s Jewish humor compilation. Finally, following three days of work and a zillion particles of dust, we were done with the thousands of books and began putting other objects away. In a cardboard box were some twenty pipes. Kaniuk asked me to toss about half of them. With his permission, I pocketed three.

۞

Having learned how to pack a pipe from several lovely YouTube clips, I took the handsomest to town last night. The evening began with the opening of The Atlas Marker, an exhibition of Shahar Sarig‘s paintings and a launch of his book of the same name.

The gallery shone like a lonesome galaxy in a quiet south Tel Aviv street. It had a stone-paved back yard, perfect for the pipe, where people were drinking wine produced by Sarig’s family and speaking of art and of life. Among them were poets such as Ronny Someck and Hagit Grossman; and artists, like Elad Rosen and Moshe Gerson, who doubles as a spoken-word prodigy. There were also people whose art is more difficult to pin down, such as veteran historian Shlomo Shva, who is responsible for a knock-out compilation of early Hebrew journalism, perhaps the most eye-opening book of our history, and one of the funniest too.

I planned this post as a love letter to these people, my city’s community of arts and letters, but inevitably it will also be a letter of concern. We are living in uncertain times, in which liberals are labeled unpatriotic traitors. Despite Tel Aviv’s famed “bubble” quality, several of those present in the yard are actual activists (such as Mati Shemeolof, coordinator of the Culture Guerilla organization), and almost all hold “unpopular” opinions. This is not a community at the height of its power.

But my worry for cultural Tel Aviv has less to do with the political than with the monetary. With public support for the arts near to zero and with the book trade mechanisms depriving authors of even a meager income, this is a threatened little society. I can’t think of anything more worthwhile that was created by Israeli culture than its cultural legacy. The Hebrew language, modernized and virtually resurrected only a century ago, produced diamond after diamond.

But it’s not only the art itself that I worry for. It’s also the pipe and the stone-paved yard. The life of this city as Kaniuk knew it: its long nights, the quarrels and loves of its poets and artists, first at the legendary Cafe Kassit on Dizengof Street, where the country’s most famous literary figures used to gather; then at other winebars and cafes (most recently, at the Little Prince, which just closed). Tel Aviv is happening, it’s both gritty and stylish, its lust for life is insane. All of this is precious.

۞

Why worry when the scene is still bustling, when artists brave the financial setbacks and the energy of the city is high? Perhaps I’m just a pessimistic hill dweller. We’ve already lost one city, you see. Jerusalem still boasts several great art and cinema schools, so there’s young creative blood there, but these kids are prone to head for the coastal plane as soon as they graduate. Most of their professors are Tel Aviv natives, as are, for example, nearly all actors at the Khan, Jerusalem’s only repertory theater.

This didn’t use to be the case. The stone paved yard at the gallery made me think of the lush patio at the Ein Kerem Music Center. The remnants of Jerusalem’s arts community, gray-bearded painters wearing berets and aging hippie ladies in long braids, gather there on Saturdays for chamber music concerts. The last time I smelled pipe smoke before lighting my own must have been there, and it was faint, too faint.

The ultra-Orthodox are most often blamed for scaring Jerusalem’s liberal crowd away, but of course the fault is all ours. My parents left when I was a child. As a teenager I toyed with the idea of returning there, then dropped it. Jerusalem’s old arts scene, which featured such greats as poet Yehuda Amichai, is not likely to regain its vigor. It is a lost civilization.

And what will be of Tel Aviv? The brain-drain from the young arts community is serious, and the powers that be do nothing to stop it. Why would they? The fewer young liberal leftists around, the better for them. Berlin is where everyone is heading, though New York and London are also seen as attractive. Our musicians are already there, our artists and photographers follow bit by bit. Actors and writers have more of a problem, being confined by language, but we too dream of foreign climes. Yours truly makes sure to get some practice by blogging in English.

When we do pack up and go, all of this will be history. The line that began with Bialik, still alive in Kaniuk’s study, will be disconnected. The treasures on those shelves will have the value of museum pieces, if any value at all. Who will care for Dahn Ben-Amotz’s groundbreaking erotic novels? They are not necessarily enormous literature, just a hint that something intense happened here, once, something that we, like beginner pipe-smokers, did our best to keep alight.