Mubarak Awad, one of the main organizers of nonviolent resistance during the First Intifada until Israel exiled him, talks about why only nonviolence can defeat the occupation, how Palestinians must convince Israelis that peace is their own interest, and his fears that without a new nonviolent movement more and more Palestinian youths will be drawn to armed resistance.

By Waleed Shahid (First published in ‘In These Times‘)

The largest Palestinian uprising in the history of the Israeli occupation is largely forgotten today. In the 1980s, thousands of Palestinians took part in large-scale civil disobedience actions, strikes, pickets, boycotts and sit-ins demanding freedom, later becoming known as the First Intifada, the Arabic word for “a shaking off.”

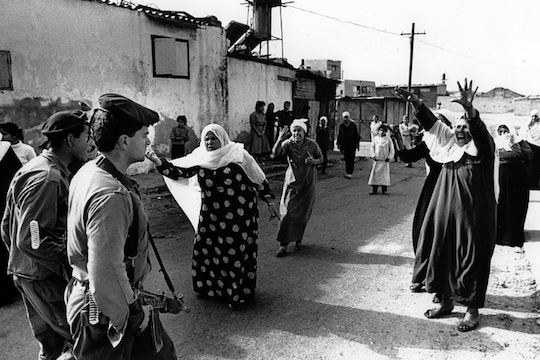

Images of Israeli soldiers clashing with Palestinian teenagers, women and the elderly circulated worldwide as the three major American nightly news broadcasts dedicated more time to the intifada than to any other story. While the “stone thrower” became the dominant image in the later stages of the intifada, vastly underreported were the daily decisions by Palestinians to refuse to cooperate with the Israeli occupation without using weapons.

The intifada polarized Israeli society between those who supported peace with the Palestinians and those who desired increased repression of the resistance.

“Frustration [inside Israel] also stems from the fact that many Israelis, of all political persuasions, have come to feel that where the conflict with the Palestinians is concerned, their country is living a lie,” described two Israeli writers in 1989. “They now believe that their leaders deceived them in pronouncing that the Palestinian people did not exist; that the Arabs in the territories did not want their leaders; that the PLO forced itself on the Palestinians by violence and intimidation; that the status quo of occupation could be maintained indefinitely.”

By 1988, more than 500 Israeli military reserves signed a petition refusing to serve in the Palestinian territories, claiming that the IDF’s presence in the Palestinian territories was immoral and undermined Israel’s own security. The Israeli organization Peace Now mobilized thousands of Israelis demanding a negotiated end to the conflict. In 1989, villagers in Beit Sahour engaged in six weeks of civil disobedience, publicly burning their Israeli identity cards and refusing to pay taxes to Israeli authorities.

The intifada did not end the Israeli occupation, but it did break end the decades-long stalemate between Israeli and Palestinian negotiators. More importantly, it made the Palestinian cause a legitimate and urgent one and even convinced a majority of Israelis for the first time that a diplomatic rather than military solution to the conflict was necessary.

Mubarak Awad was one of the main organizers of the nonviolent resistance during the First Intifada. He spent many years in the United States as therapist and counselor of “at-risk” teenagers, before moving to the West Bank to work with Palestinian youth who had experienced violence. After studying the writings and practice of Mahatma Gandhi, Martin Luther King and Gene Sharp, Awad began translating their work into Arabic and left hundreds of pamphlets about tactics of non-cooperation and theories of power in bus stations and on village notice boards all across the West Bank.

Awad eventually went on to create the Palestinian Centre for the Study of Nonviolence, which trained Palestinians in nonviolent civil resistance. Awad urged Palestinians to plant olive trees on proposed Israeli settlements, refuse to carry and present Israeli ID cards, block roads with their bodies, publicly defy curfews, defy the law by flying Palestinian flags and obstruct the movement of Israeli equipment. He also advanced the concept of “filling the jails” by promoting the civil rights movement’s concept of mass arrest. Over 29,000 Palestinians went to jail during the first year of the intifada.

Awad, along with many of the leaders of the resistance, was jailed, tortured and eventually deported by Israel in 1988 for circulating leaflets encouraging civil disobedience. Today, 72-year-old Awad’s experiences and strategies of resistance are fairly unknown to most people outside of the West Bank. Awad now lives in Washington, D.C. and teaches about nonviolence at American University. I recently spoke with Awad, about his visions and experience of civil resistance in Israel and Palestine.

In the 1980s, you boldly declared to Palestinians, “We are under occupation because we choose to be under occupation.” What does that statement mean?

Every human being is responsible for his or her action even in the most difficult of situations. We have choices to make—the choice to resist, to run away, or to do nothing. If we do nothing, then we are accepting the status quo: the occupation. We are accepting the occupation as our lives. We must take responsibility and leadership for what has been done to us and what we are doing to ourselves. Gandhi talked about the British being able to control hundreds of millions of Indians with only a few hundred British soldiers. He made the same claim: that millions of Indians were letting the British control them by simply cooperating with British rule every single day.

I wanted to challenge Palestinians to take responsibility for themselves and their situation. Resisting evil with the gun is one method, but we can also resist evil with nonviolent means. But that means discipline, strategy, training, and knowing your opponent. I wanted Palestinians to push ourselves to create space for elements within our opponent’s side to defect to our side. If we cannot convince large amounts of Israelis to agree with us, we will never win.

This is a civil rights struggle. This isn’t about expelling the Israeli and the Jewish people. In some way or another, both sides must become friends and see themselves in each other. The goal and objective is simple: end the occupation. We aren’t talking about the status of Jerusalem or refugees or administrative issues. We are just talking about our lives. Nothing else happens until the occupation disappears. And it is up to us to force it to disappear because no one else will.

And you began your involvement in anti-occupation efforts in Israel and Palestine because you felt the nonviolent resistance piece was missing. Can you describe the void you were trying to fill in the 1980s?

At that time, the leadership claiming to represent the Palestinian people was the Palestine Liberation Organization. But their headquarters was not even in Israel or Palestine. They were living in exile. That created difficulties and a lack of venues for ordinary people to get involved. The Israeli government opposed the PLO and would put its leaders and members in jail with frequency. The Israeli government wanted an alternative to the PLO. They wanted to negotiate with Jordanians and Egyptians. They were pushing hard and eventually helped create the spark for Hamas.

This created a general feeling that ordinary Palestinians had to rely on other people to resist the occupation. There was no venue for the people to take action for themselves.

At that time, I was trying to explain to people that there were all kinds ways to get rid of the occupation. The PLO at that time was open to all venues of struggle, but really saw itself as a vanguard similar to anti-colonial groups like the Algerian National Front. I wanted to bring attention to Palestinians to understand the strategies and tactics of what was done in India by Gandhi and his followers, and with Martin Luther King in the American South. I wanted to explain nonviolence for Palestinians and suggest that it could work in Palestine and to train new leaders in disciplined nonviolent resistance.

At that time, the PLO didn’t have a coherent strategy, but they basically were training a very limited number of people in armed struggle. But violent resistance doesn’t involve the whole of society. Violent resistance reduces the participation of children, women and the elderly. It reduces participation of most sectors of society that aren’t young men. Violent resistance would make people even more afraid to come out and act together. Armed struggle is unable to involve the majority of society to oppose occupation.

And it was incredibly naive and romantic. The handful of people who were trained in armed struggle were no match for the Israeli military. We had a few secondhand guns; the Israelis have tanks and airplanes. It’s not sensible and not strategic; it backfires on your own people. It’s not an equal field. They will always beat us if we choose violence—or choose to resign ourselves to the occupation. I wanted to say: “We can’t keep continuing to play the same game after decades of defeat. Let’s try something different.”

What is nonviolent civil resistance?

Nonviolent civil resistance is simply trying to help people find what was taken from them. Thousands of people doing coordinated civil disobedience, strikes, boycotts, sit-ins—through these kind of actions, we try to negotiate with the opponent in a different way. It means trying to get the whole of society to act together not to necessarily harm the opponent, but to make them actually deal with us and our humanity, deal with our willingness to stand up for ourselves with nothing but our bodies and hearts. That is the logic of nonviolence.

In Selma and Birmingham, Martin Luther King wanted to show all Americans not only what they were doing to African Americans, but more importantly what Americans were doing to themselves by allowing violence and racism to persist. The same thing happened in South Africa, as well. It’s powerful. It’s fighting on a different terrain. When you are willing to sacrifice everything for your freedom—without arms, even without stones—even if the government attacks you, the Israeli public will have to see you in a different way. We have to make them choose what kind of people they are.

A handful of young Palestinian men have gained widespread media coverage for committing deadly knife attacks against Israelis. You spent many years as a therapist and counselor working with Palestinian youth deeply affected by violence—both violence perpetrated by Israelis and Palestinians. How did that work affect your views on nonviolent resistance?

Young Palestinians are in a state of shock. People don’t really understand this point. Palestinians and Israelis have both gone mad. They don’t think like people who live in peaceful circumstances.

Too many Palestinians have reached the position that their lives are not worthwhile. Some young people might say that they are willing to kill someone with a knife because their future is very sad and dark. They might not get married. They might not have children. They might not have a job or an education. So what life is left for them? When people are desperate like that, things like this will happen. I am fearful of young Palestinians being recruited by armed groups, especially if there aren’t more strategic nonviolent groups willing to take them in. Violence simply breeds more violence. It’s irresponsible not to take strong stands and leadership on this issue.

The other important thing is that Palestinians are no longer listening to the older generation of elders. Their parents and grandparents couldn’t stop the occupation, so why should they have respect for them? This is also the situation I was dealing with in the 1980s. The occupation was breaking families apart. Young people want to do whatever they can in the moment to satisfy for their own thirst for freedom. Talking violently or acting violently for them is to assert some sort of control over their lives, even if it hurts their own families.

The Israeli public is so afraid of the Palestinians. It’s so amazing: The Israelis deprive Palestinians of everything, but they are still so afraid of us. Many want to create a Jewish state without any real rights whatsoever for Palestinians. We can’t give them more reasons to be afraid.

It’s becoming more common for activists to refrain from explicitly condemning violent acts of resistance by Palestinians, but instead contextualize those acts as the product of the structural violence as a result of Israel’s occupation. Where do you land on that?

We know what the Israeli government is doing: They wantonly arrest and hurt and even kill Palestinians. But we as Palestinians have to be better than them. Some people don’t like when I say that, but it is true and it is not going to change anytime soon. Throwing stones, wielding knives, launching rockets—this is not the right way. It scares our own people and it scares the Israelis even more. It shouldn’t be our intention or strategy to make them more afraid and feeling more insecure as individuals. Many Israelis are afraid to leave their homes, as well. What kind of strategy would make the Israelis come to us and say “we need your help to fix this disaster once and for all? As Israelis we are tired of living like this, doing this to you, doing this to ourselves.” That means we have to raise the bar for what real reconciliation, acceptance and coexistence means. We can find that in our three religions if we look for it with honesty.

It sounds like you are saying the main people Palestinians have to convince are the Israeli public?

If you are able to convince many Israelis that it is in their self-interest to have peace with their Palestinian neighbors, then the Israelis would vote for a prime minister who wants real peace. Right now, the Israelis don’t think it is in their self-interest, in their values as human beings. That is up to us as Palestinians to decide whether we actually want to use that kind of strategy or not. Nonviolence takes up the question of the occupation and sends it back to the opponent, telling the Israelis that it is now their choice to decide. That is exactly what King did in Birmingham and Selma.

Look, I don’t have a reason to like Israelis. They killed my father. They destroyed my house. They’re destroying my culture. They destroyed my life. They’re continuing to destroy the lives of my family back home, coming in the middle of the night and arresting Palestinians from their homes. They block our roads. They take our land. They aren’t showing an interest in wanting peace with us.

But we still have to take the strategies of nonviolence and show the way forward. It is very tough and very hard. People on both sides want to take the easy way out and not grapple with fundamental issues. But we have examples of who were able to do the impossible: Gandhi, Martin Luther King, Nelson Mandela, even Northern Ireland. The only conflict that is not resolved is ours. And we must all accept the responsibility for that. It can only truly be resolved when we decide to condemn bloodshed from all sides.

You distinguish between principled nonviolence and strategic nonviolence. Why is that distinction important?

Principled nonviolence is what we learn in religion as Jews, Christians, Muslims and all people of faith. We all worship a God and that God tells us to make good with each other. We are created by God. And inside every person there exists a piece of God that we should not harm. We don’t have the right to harm or kill any person. And if we don’t have the right to kill anyone, we have to learn a different kind of discipline.

Strategic nonviolence is about political considerations. You don’t have to believe in principled nonviolence to believe in strategic nonviolence. It’s not about personal morals and interactions. It’s about using nonviolence militantly, like a kind of unarmed warfare. You have to deeply understand power. We have to have thousands of people involved, and active participation—especially from women and older people—severely declines when the resistance is seen as violent.

And for that you really have to understand where the Israelis are coming from. They have the guns and the laws. We don’t have those things. We must pick a different method to create the kind of situation that would make them demand an end to the occupation from their own government.

But there is so much anger within both the Palestinian and the Israeli people. How can we understand the Israelis, so that we can trust them and they can trust us as human beings? That is a huge challenge. Some people are not interested in that question. But it is the only way to solve this thing for the long term.

What are the important lessons to draw from the First Intifada?

When thousands of people get together in the street for strategic action, they can achieve something. We were able to get the Israelis and Americans to talk to the PLO for the first time. The PLO didn’t make that happen—the people did that. We brought the occupation into television screens all across the globe, and most importantly, we brought our humanity into Israeli living rooms. The second thing we achieved was real negotiations for the first time with the Israelis. We put out the idea that life would be better for both peoples, if our representatives would simply talk to each other.

It didn’t turn out the way we thought it might. The Israeli government doesn’t want peace. It still doesn’t. We were just dreamers, dreaming of peace, trying to get both sides to understand that peace was achievable for everyone. But I don’t think the Israeli government wants a two-state solution. They want to keep the status quo going. They think time is on their side.

Can you tell me about the most inspiring nonviolent action you took part in?

I used to go to villages and talk to people about nonviolence and non-cooperation with the Israelis. I had gone to 300 or so of them before I was deported. Some people accepted my ideas, some rejected me. We would just go into homes and work with as many people as possible to talk about power and tactics and their lives. One day, someone from one of the villages came to my office and said he needed nonviolence. And I asked him what did he mean? So he explained that settlers had come and put a fence around his land and that he needed to take his land back. Now he needs nonviolence.

At first, it was tough for me because I was simply explaining concepts to people. I wasn’t a real strategist. But he kept saying he didn’t care about the concept—he wanted it in his life right then and there. So I told him if he could bring the whole village out—the women, the men, the children, the elderly—we should take the fence out of the ground ourselves. And we shouldn’t run away when the police or military or settlers come. We should just stay there and sit-down. We shouldn’t throw stones. We should just stay and refuse to leave.

It took us five hours to take the fence down and eventually the settlers called the military governor of Bethlehem. We talked to him and eventually he declared that the land belonged to us.

Now imagine if we could do that on a scale of thousands of people? The action worked because of the Palestinians’ commitment to their cause and to their humanity. We were willing to show that we would sacrifice everything—being arrested, being attacked—but without ever hurting anybody. Today, we need more Palestinians to return and train people in in nonviolent tactics and strategies. That is also what happened during the First Intifada.

What is different about nonviolent resistance amongst Palestinians today and nonviolent resistance during the First Intifada?

I still think the Palestinians have to really commit themselves to nonviolence. They can’t accept both violence and nonviolence. We really have to come to terms with the idea that we cannot defeat the Israelis with violence. They will always win. I was beaten many times for my people. I am very sad and disappointed. But I still believe that nonviolence is the only way. But it requires real strategy, leadership, training, and discipline.

Waleed Shahid is Philadelphia-based writer and the political director of Pennsylvania Working Families Party. He is a movement-building trainer with Momentum and tweets at @waleed2go.