A Palestinian author hosted an Israeli colleague for what should have been an urbane literary evening in a fine bistrot. Not everybody in the audience had the same idea.

“I’m beginning to get worried about all these enemies around us”, Yoram Kaniuk says, with conscious irony, as the dinner plates are removed from the table and the time for his Nazareth talk approaches. “They’ll blame me for the Nakba, I’m telling you.”

We are at “Sudfeh” an excellent Bistro and symbol of the city’s rejuvination. Nazareth’s population is part Christian, part Muslim. All are Palestinian citizens of Israel. The wrecking of villages during and after the 1948 war greatly let to this city’s growth. Even Kaniuk’s host, local author Odeh Bisharat was born in the village of Ma’alool.

Is Kaniuk to blame for the Palestinian disaster? He did fight in that war when 17 years of age. His record of those times recently appeared as a book entitled “1948”. It is one the biggest Hebrew bestsellers of the year, breaking every record this renowned Israeli author set in the past.

Bisharat knows that any Israeli who took part in the war may be viewed here as war criminal. he kicks off the talk by quoting a portion of “1948” dealing directly with the expulsion of the residents of Lyddah and Ramla. “A huge broom went over the city and swept everyone out,” Kaniuk wrote, “the women, the children, the old, the young. It left only the spaces where they were.”

This is a good start. Kaniuk is shown to have a conscience and he does. Following the war he became a strong porponent of Arab rights in Israel. Together with Palestinian author Emil Habibi. The two formed an “authors allience” that fought for the romoval of martial law from Arab communities, against land confiscation et al. Kaniuk, who has more than once contributed texts to this site, is a Zionist, but one who can draw such an audience in an Arab city that new chairs have to be brought constantly from the Sudfeh’s stone paved courtyard.

No, they called themselves Arabs!

He kicks off by saying that he was present at the decisive moment of the war. “The Arabs held on to the ‘Kastel’ (A hilltop stonghold to the west of Jerusalem, YB.) which meant we couldn’t reach Jerusalem at all, but then their leader, Abd Al-Kader Al-Khousseini died, and they had to go to his funeral in the city. The positions were vacated and we took over. If that hadn’t happened, the outcome would have been the opposite.”

This is when the first call comes from the audience: “Why do you say Arabs?” says a woman in her thirties with cropped hair and a yellow shirt. “They were Palestinians.”

“At the time the word “Palestinians” was not yet in use,” says Kaniuk. “Nor was the word “Israelis” in use. We were Jews, they were Arabs.

“You called them Arabs. But they called themselves Palestinians.” The woman insists.

“No, they called themselves Arabs! Look, today I also use “Palestinians” but then we were all subjects to the King of England, and we thought of ourselves as Jews and Arabs. Yes, the word ‘Palestinian’ existed. I am Palestinian, it says so in my birth certificate from 1930. I was born in British-ruled Palestine, but the Jews were Jews and the Arabs were Arabs.”

A Palestinian (Arab?) gentleman from the back of the room comes to Kaniuk’s help: “The forces that fought against the Palmach were not only local, they were Arab forces, from Syria, Jordan, Iraq…”

The lady in the yellow shirt wishes to contradict but Bisharat gains control of the room and Kaniuk resumes talking. He is extremely careful not to say the word “Arab” anymore. All “Arabs” are now “Palestinians”. While at first the switch demands some thinking and near slips are registered, it soon becomes more or less natural.

The change of terminology, however, does not imply a complete change of paradigm. At one point, having just mentioned the Jordanian legion, Kaniuk turns to the lady in the yellow shirt and asks: “Can I say ‘Jordanian’? Is that an acceptable term?”

“Arab is a term used by the Shaback,” she retorts, alluding to the “Shin Bet”, the secretive policing apparatus employed mostly to police palestinians. “if you are in favor of the Shaback, say Arabs!”

Kaniuk shrugs and asks to talk about literature.

Boring and Zionist

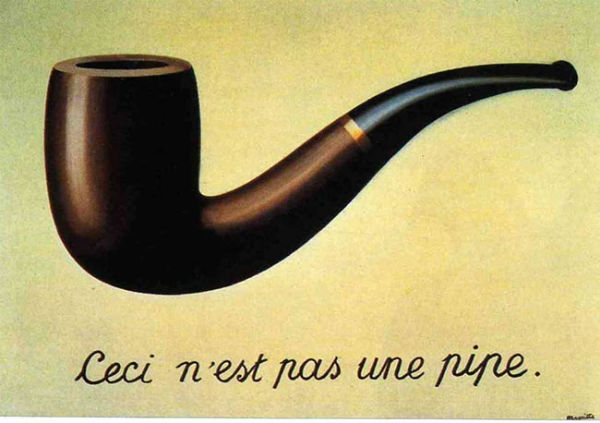

It seems that we can gather in one room, honestly determined to talk about difficult issues, but even then we don’t know what to call each other and fail on the onset. The first word uttered in the entire evening was too controvesial for the evening to go on as planned, and the issue kept recurring.

This is nothing new to anyone involved. In Bisharat’s novel, “Streets of Zitounya”, a satirical record of municipal elections in an Arab (Palestinian?) town, Jewish Israelis are not mentioned at all. Like Iranian filmmaker Abbas Kiauristami, who for many years refused to feature women in his films so as not to deal with government censorship, Bisharat made an attempt to stay out of any cheap debate.

Kaniuk wrote one other book dealing with the conflict. That book is entitled “Confessions of a good Arab”. It’s protagonist is half Jewish, Half Palestinian. He brags now that the book was translated into Arabic and published in Syria. He also takes a second to explain its controvesial name: “It is, of course an allusion to the racist saying some people use in our society: A good Arab is a dead Arab”.

Having traveled to Nazareth with Kaniuk I know that the word “Arab” is certainly no slur when pronounced be him (“The Arabs build such beautiful cities” he said as we passed Umm Al Fahm, “We Jews just build those awful things that look like rows of tombstones”). At the same time, the lady’s position is understandable. In Istraeli discourse the term “Palestinian” was rejected for decades. We were tought that Palestinian nationality is a myth, a contrived invention created as an excuse of Atrab nations to push us “into the sea”.

Calling the Palestinians “Arabs” also implied that they could easily merge into the rest of the Arab Middle East and disappear. There’s no difference, we were told, between them and the Lebanese, or Lybians, or Bahrainis, so why don’t they just go there and shut up?

This is not, however, what Kaniuk meant to say, and sticking to offensive contexts rather than listening is counterbeneficial to any dialogue. As the lady in the yellow shirt leaves the room I follow her, politely asking who she is. She waves me off, muttering that the evening was “Boring and Zionist”.

I can empathize with her. I can see why Kaniuk’s use of terminology would upset her. but an evening like this is only boring and Zionist if you stick to one word and use it as barrier, blocking off any worthwhile idea that is expressed. An obsession with words will lead us nowhere, since each side learned to assume a certain terminology and read into it a certain way. This is exactly where we must begin to liberate ourselves.

I watch her as she returns her beer glass to the bar, turns her back on me and leaves. Then I return to the room she left behind, hoping to hear something new.