The three Arab lists in the Knesset are expected to run together in response to a raised election threshold. Asked about self-identity, the majority consider themselves Arab, but a growing and significant minority call themselves Palestinian.

Nearly 70 percent of Arabs citizens of Israel intend to vote if the three existing Arab parties run on a joint list, compared to 56 percent who voted in the 2013 elections, a new +972 poll found. But the call to boycott the elections holds powerful sway. A majority of 54 percent says that if there are such calls to boycott the elections, they will decide not to vote, leaving only 46 percent at present who are committed to voting despite such calls.

As the wave of speculation about unification of the three Arab lists swells, there is a flurry of concern about low voter turnout in the Arab community. Since the boycott against elections in 2001 when fewer than 20 percent voted, recent cycles have seen just half of Arab voters participating. The newly raised electoral threshold means that any one Arab party might not be represented in the Knesset, unless they run together.

Click here to read more on the +972 poll here

There has been a presumption that Arab voters are fed up with party politics and ego games just as much as Jewish voters, and that for Arabs, uniting would give people a boost of faith in their representatives’ willingness to put personal interest aside, to better represent the people.

And sure enough, by contrast to other indications that still only half of Arab voters will participate based on the current lists, we found the following:

• When asked “if the parties unite into one list, what are the chances that you will participate in voting?” 68 percent of Arab respondents said they would “definitely” vote, the closest indicator of actual intentions.

• One-third (32 percent) in total responded “possibly,” “there’s a 50-50 chance,” or “I won’t vote.”

Yet against this new finding, the threat of calls to boycott still lurks. Respondents to this survey were very mindful of the possible call to boycott. We asked:

“If leaders in the Arab community call to boycott and not participate in the elections, will you vote despite that, or will you decide not to vote?”

• A high portion, 40 percent, say that in such a case they will definitely not vote, showing not only responsiveness to the call of boycott, but high intensity.

• In total, 56 percent say that if there are calls for boycott, they will heed them and will not vote.

• That leaves just 46 percent who said they will definitely or probably vote despite such a boycott.

• Interestingly, those who will vote also display high intensity: twice as many say they will definitely vote (33%) despite the call to boycott, as opposed to those who say they probably will (13%)

• Another interesting tentative observation: we asked Arab respondents to choose their primary identity. Those who identified first of all as Palestinian, rather than Arab, were slightly more likely to say they wouldn’t vote if there were a call to boycott. These are just small cells, but it does indicate a distinction of political attitudes.

Who am I?

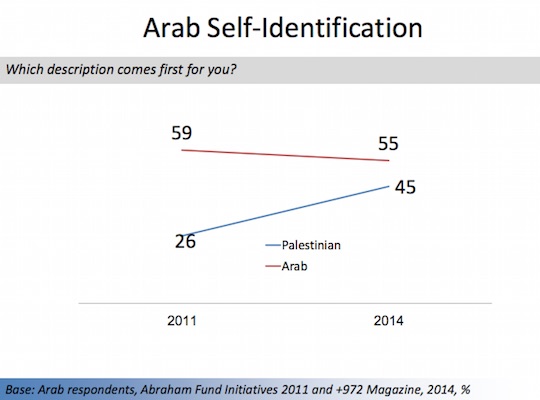

The self-identification findings are interesting on their own. We gave four options – Arab, Arab-Israeli, Palestinian, and Palestinian-Israeli. We did not ask people to pick one exclusive definition, but to say which one is primary or comes first for them.

In the current sample, 55 percent chose one of the descriptions defined by “Arab” – either Arab or Arab-Israeli. A large minority, 45 percent, chose either Palestinian or Palestinian Israeli.

With caveats for the small sample, this could represent a significant shift from 2011, when I asked the identical question in a survey I conducted for the Abraham Fund. At that time, a greater majority – more than twice as many – identified as Arab before Palestinian (59 percent to 26 percent, respectively). And the main shift is not a decline in Arab identification but a rise in Palestinian identification. This is a finding that shifts over the years, but if confirmed, it would not be surprised to find that the series of nasty incidents, legislation and incitement against Arabs over the last few years could easily be pushing people to embrace a distinct identity that is more politicized.

It is important to note one reservation: the survey included a limited sample of 100 Arabs, which means that among this sample alone there is a high margin of error, around 10 percent. However, the broad trends are still clear because the findings show large majorities, and this gives comparative legitimacy to the findings that divide Arabs, such as the boycott call. Interviews were conducted by phone, in Arabic.

The survey was designed and analyzed by Dr. Dahlia Scheindlin, a public opinion expert and political consultant who advises national campaigns in Israel and internationally, and holds a doctoral degree in political science from Tel Aviv University. Data collection was conducted by New Wave Research. The research included a representative sample of 600 adults, Jews and Arabs, interviewed in Hebrew and in Arabic. The interviews were conducted by Internet and phone, from December 11-17, 2014. The margin of error is +/-4%, higher for each sub-sample. See the raw data in Hebrew here.